Fact check: Yvan De Baets on saison (and the results may shock you)

A saison, anyone? For thousands of drinkers and brewers, Phil Markowski’s 2004 book Farmhouse ales, and especially the contribution it includes by Belgian brewer Yvan De Baets, has shaped the notion of what the beer type saison is or should be: a so-called ‘farmhouse ale’. But has anyone actually checked the sources on which all this is based? Especially for you, I will do so now. Warning for saison lovers: this may shake some firm beliefs you have cherished for a good part of your life.

A saison, anyone? For thousands of drinkers and brewers, Phil Markowski’s 2004 book Farmhouse ales, and especially the contribution it includes by Belgian brewer Yvan De Baets, has shaped the notion of what the beer type saison is or should be: a so-called ‘farmhouse ale’. But has anyone actually checked the sources on which all this is based? Especially for you, I will do so now. Warning for saison lovers: this may shake some firm beliefs you have cherished for a good part of your life.

In a few preceding articles I’ve been looking into the history of saison. This beer type has enjoyed a no less than colossal revival over the past decades: thirty years ago, only a few rural breweries in the province of Hainaut (in the French-speaking part of Belgium) were making it, today ratebeer.com counts over 12,000 different saisons brewed worldwide, and untappd.com lists no less than 43,390.

A major boost for its popularity was the 2004 book Farmhouse ales by American brewer Phil Markowski, currently brew master at Two Roads Brewing in Stratford, Connecticut, USA.[1] In the book, Markowski described the different Belgian saisons of that moment, defined what saison is and gave guidelines for brewing it, and also for its Northern French counterpart bière de garde. The bottom line of the entire book is: saison is what it is because originally it was a ‘farmhouse ale’, brewed on Belgian farms in wintertime to quench the farm workers’ thirst in summer.

A major boost for its popularity was the 2004 book Farmhouse ales by American brewer Phil Markowski, currently brew master at Two Roads Brewing in Stratford, Connecticut, USA.[1] In the book, Markowski described the different Belgian saisons of that moment, defined what saison is and gave guidelines for brewing it, and also for its Northern French counterpart bière de garde. The bottom line of the entire book is: saison is what it is because originally it was a ‘farmhouse ale’, brewed on Belgian farms in wintertime to quench the farm workers’ thirst in summer.

It’s a book that has inspired a lot of people worldwide, and saison is now being brewed everywhere from Trinidad to Tokyo, by people who think they are part of a Belgian farmer’s tradition. It helped to spread an until then quite unknown and probably endangered beer type, and it boosted sales of great Belgian beers, especially the beer that is definitely presented as the standard: Saison Dupont, from the Dupont brewery in the small Hainaut village of Tourpes.

Therefore, it may come as a shock to saison lovers that this influential book actually shows how Phil Markowski is oddly unaware of the very basics of Belgian geography and history. For instance, somehow he thinks that Wallonia and the French departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais were ‘once collectively known as Flanders’. Unfortunately, this is a laughable assertion to anyone who even remotely knows anything about Belgium, its politics and its linguistic problems. No less unfortunate is the mythical ‘Kingdom of Flanders’ Markowski somehow invents, as well as the border that according to Markowski has divided Wallonia and the French departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais since 1831. (I hate to tell you this, but there never was such a kingdom and the border dates from 1713).[2] To put it differently: to a Belgian, saying Wallonia is part of Flanders is like saying New York City is part of Canada. It makes you think: if Markowski couldn’t get this right, why should we trust him on the farmhouse story?

Therefore, it may come as a shock to saison lovers that this influential book actually shows how Phil Markowski is oddly unaware of the very basics of Belgian geography and history. For instance, somehow he thinks that Wallonia and the French departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais were ‘once collectively known as Flanders’. Unfortunately, this is a laughable assertion to anyone who even remotely knows anything about Belgium, its politics and its linguistic problems. No less unfortunate is the mythical ‘Kingdom of Flanders’ Markowski somehow invents, as well as the border that according to Markowski has divided Wallonia and the French departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais since 1831. (I hate to tell you this, but there never was such a kingdom and the border dates from 1713).[2] To put it differently: to a Belgian, saying Wallonia is part of Flanders is like saying New York City is part of Canada. It makes you think: if Markowski couldn’t get this right, why should we trust him on the farmhouse story?

At least, Markowski had the good sense of asking a Belgian to write the chapter about the history of saison. Like Markowski, Yvan De Baets is a brewer. Then working at De Ranke brewery in Dottignies (which is, admittedly, a rare Flemish brewery in Hainaut), he would shortly after co-found the well-known Brasserie de la Senne in Brussels. De Baets made a great contribution to the Belgian beer scene and has created wonderful beers. Also, his contribution to Farmhouse ales for many has become a classic reference when it comes to saison and its history.[3]

At least, Markowski had the good sense of asking a Belgian to write the chapter about the history of saison. Like Markowski, Yvan De Baets is a brewer. Then working at De Ranke brewery in Dottignies (which is, admittedly, a rare Flemish brewery in Hainaut), he would shortly after co-found the well-known Brasserie de la Senne in Brussels. De Baets made a great contribution to the Belgian beer scene and has created wonderful beers. Also, his contribution to Farmhouse ales for many has become a classic reference when it comes to saison and its history.[3]

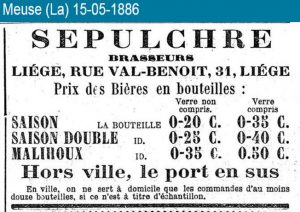

In fact, De Baets’ article is the only text I know on the history of Belgian saison. In it, De Baets paints a rather idyllic picture of the brewing farmers of Hainaut who, so to speak, hardly ever left the farmyard. That’s why I was surprised when I recently found out that most historical evidence I found myself on this beer type, didn’t really align with what De Baets is saying in his famous article. Surely, also in the past saison was defined as a beer brewed ‘in the good season’ (i.e. winter) that was kept for a few months or more. However, I found a lot of 19th century professional breweries making and selling saison in cities, especially Liège, which isn’t even part of Hainaut. I felt it was time to give De Baets’ article a very close reading and see what exactly he is basing himself on.

Clearly, De Baets spoke to the people at Dupont brewery and some other (former) brewers. He may have looked at their archives as well. Also, he tasted some old bottles of saison and drew some conclusions from that. Still, it is rather odd that although De Baets admits that ‘very few written records exist’ for the rural beers he is writing about, he somehow still feels confident enough to proclaim that the saisons of today are ‘similar to those of the past’.

Clearly, De Baets spoke to the people at Dupont brewery and some other (former) brewers. He may have looked at their archives as well. Also, he tasted some old bottles of saison and drew some conclusions from that. Still, it is rather odd that although De Baets admits that ‘very few written records exist’ for the rural beers he is writing about, he somehow still feels confident enough to proclaim that the saisons of today are ‘similar to those of the past’.

In any case, what De Baets relates about early 20th century saison seems plausible. Around 1900, saison must have been relatively sour. Also, it was weaker than today’s saison at around 3 to 3.5% ABV. Only during the course of the century did saisons become less sour and more bitter. Also, they got heavier, between 4.5 and 6.5% ABV, and in the end saison became a beer that was brewed year-round. De Baets describes the rural context these saisons had at Dupont and elsewhere: in the first half of the 20th century, farmers would go to a local brewery a few times during winter, and brew a reserve of saison. Marc Rosier of Dupont relates that before the Second World War, farmers would take bottles of saison to the field and put them in a hole in the ground to keep them cold. I have no particular reason to doubt that: I’m sure that’s what happened in that particular rural part of the region by that time. My idea is however, that it is a very narrow view of what saison actually was.

De Baets says a few things I’ve dealt with in earlier articles, such as the idea that ‘it was almost out of the question to brew in the summer’ or that ‘saisons originated in Wallonia, in southern Belgium, with an important concentration in the province of Hainaut.’ In short: there certainly were breweries in Belgium that continued to produce throughout summer, and saison was much more a typical beer from the province of Liège than from Hainaut.[4] De Baets gives no source for the ‘saison was brewed at the farm for the farm workers’ story, apparently considering it common knowledge. In reality, the oldest reference to this narrative I found so far only dates from 1989, by an author who clearly based himself on what the people at the Dupont brewery told him. I’ll get back to this in an upcoming article.[5]

De Baets says a few things I’ve dealt with in earlier articles, such as the idea that ‘it was almost out of the question to brew in the summer’ or that ‘saisons originated in Wallonia, in southern Belgium, with an important concentration in the province of Hainaut.’ In short: there certainly were breweries in Belgium that continued to produce throughout summer, and saison was much more a typical beer from the province of Liège than from Hainaut.[4] De Baets gives no source for the ‘saison was brewed at the farm for the farm workers’ story, apparently considering it common knowledge. In reality, the oldest reference to this narrative I found so far only dates from 1989, by an author who clearly based himself on what the people at the Dupont brewery told him. I’ll get back to this in an upcoming article.[5]

Anyway, things really go off the rails when De Baets wants to make it any more specific than that. For the details, De Baets consulted 19th and early 20th century brewing manuals and made a few more or less educated guesses. I’ve looked at the same works to see what exactly De Baets is basing himself on. What is to follow now, may shock saison lovers.

Let’s have a look at the grains used by the ‘farmhouse breweries’ De Baets wants to describe. He claims that they ‘usually grew their own barley and malted it themselves’. To confirm this, De Baets quotes a brewing manual by Cartuyvels and Stammer from 1879, on the primitive kilns used in Hainaut. But when you look up that old book and see what these gentlemen actually say on beer in Hainaut, you read: ‘malt is generally prepared in breweries… The grains used are most often six-row barley from the region, from the polders [=Flanders], from Beauce [Central France], Vendée [Western France] and barley from the Danube.’[6] Does that sound like home-grown barley malted by farms (not breweries)? Not to me.

Let’s have a look at the grains used by the ‘farmhouse breweries’ De Baets wants to describe. He claims that they ‘usually grew their own barley and malted it themselves’. To confirm this, De Baets quotes a brewing manual by Cartuyvels and Stammer from 1879, on the primitive kilns used in Hainaut. But when you look up that old book and see what these gentlemen actually say on beer in Hainaut, you read: ‘malt is generally prepared in breweries… The grains used are most often six-row barley from the region, from the polders [=Flanders], from Beauce [Central France], Vendée [Western France] and barley from the Danube.’[6] Does that sound like home-grown barley malted by farms (not breweries)? Not to me.

De Baets also quotes French beer writer Georges Lacambre (1851) on kilning, but picks it from a section on Walloon brown beer, a beer type that according to Lacambre (contrary to saison) was usually drunk fresh.[7] Then, De Baets references Vanderstichele (1905) on malting barley for bière de garde, but De Baets somehow fails to communicate that the original text recommends barley from the polders, especially from the district of Cadzand (in the Netherlands, right across the border)![8]

Conclusion: did these idyllic farmers grow their own barley? Not if the sources De Baets misquoted are anything to go by.

Then, there’s hops. De Baets quotes Cartuyvels and Stammer on the quantity of hops used, but then goes on to say that ‘it is well understood that Belgian hops, traditionally grown in the province of Hainaut, were most often used since they were grown near the brewery and were the most readily available.’ Unfortunately Cartuyvels and Stammer actually say something quite different on the hops used in Hainaut beers: ‘The hops that are most often used are those of Aalst and Poperinge’.[9] As you may know, these places are in Flanders, and not in Hainaut ‘near the brewery’.

Then, there’s hops. De Baets quotes Cartuyvels and Stammer on the quantity of hops used, but then goes on to say that ‘it is well understood that Belgian hops, traditionally grown in the province of Hainaut, were most often used since they were grown near the brewery and were the most readily available.’ Unfortunately Cartuyvels and Stammer actually say something quite different on the hops used in Hainaut beers: ‘The hops that are most often used are those of Aalst and Poperinge’.[9] As you may know, these places are in Flanders, and not in Hainaut ‘near the brewery’.

De Baets goes on to talk about the use of old hops, apparently to encourage the development of lactic bacteria that would have been incompatible with fresh hops. De Baets: ‘Farmhouse breweries would most likely have a stock of old or imperfectly stored hops on hand. The use of older hops was frequent, bringing saisons close to traditional lambic.’ He provides no evidence for this, and worse: the brewers of the ‘traditional’ lambic of the 19th and early 20th century actually used fresh hops, not old hops.[10] One would almost be inclined to believe that De Baets is simply inventing this out of thin air. It doesn’t end here. On fermentation temperature De Baets again quotes what Lacambre had to say about Walloon brown beer, again: this was a fresh beer that was completely different from saison.[11]

I have to admit, that after verifying De Baets’ claims, he really fell off a pedestal for me. All in all, I don’t believe he is giving a fair representation of his source material here. Quite the opposite, actually. So what went wrong? I think De Baets was desperate to write about what happened at farms, but found very little material to work with. Instead, he turned to brewing literature that obviously described what professional brewers were doing – and then was happy to misquote it.

I feel that if De Baets had stayed closer to what the sources are actually saying, he would have painted an entirely different picture. At least Cartuyvels and Stammer devote a small chapter on the beers of Hainaut, which do not include saison but do include ‘bière de garde, vieille ou de conserve’ which at least in definition is more or less the same thing.[12] But the only actual saison these old books talk about is the saison of Liège, which according to Vanderstichele was made in ‘the province of Liège, parts of Limburg, Luxemburg and Namur, and even [sic!] in Hainaut’.[13] It was a poorly attenuated (sweet) beer traditionally based on spelt malt. De Baets dismisses this Liège saison in a footnote as a completely different beer, referring to the current well-attenuated (dry) saisons as the only ‘true’ saisons. Sure, De Baets may choose to look at it that way, but to a 19th century Belgian, ‘saison’ almost always meant ‘Liège saison’. It is a bit unfair to walk away from that so easily.

I feel that if De Baets had stayed closer to what the sources are actually saying, he would have painted an entirely different picture. At least Cartuyvels and Stammer devote a small chapter on the beers of Hainaut, which do not include saison but do include ‘bière de garde, vieille ou de conserve’ which at least in definition is more or less the same thing.[12] But the only actual saison these old books talk about is the saison of Liège, which according to Vanderstichele was made in ‘the province of Liège, parts of Limburg, Luxemburg and Namur, and even [sic!] in Hainaut’.[13] It was a poorly attenuated (sweet) beer traditionally based on spelt malt. De Baets dismisses this Liège saison in a footnote as a completely different beer, referring to the current well-attenuated (dry) saisons as the only ‘true’ saisons. Sure, De Baets may choose to look at it that way, but to a 19th century Belgian, ‘saison’ almost always meant ‘Liège saison’. It is a bit unfair to walk away from that so easily.

More in general, Yvan De Baets wants you to believe that in 19th century Hainaut, idyllic farmhouse brewing was somehow the norm, even if Wallonia was, as I’ve stressed in a previous article, one of the most industrialised and urbanised regions in the world. He is happy to ignore that his sources are talking about professional breweries, situated in towns like Ath, Chièvres, Péruwelz, Tournai and Soignies.[14] Instead, I feel that De Baets is trying to give an idealised vision of the countryside, and by doing so he often paints himself into a corner, for instance when talking about the kraüsen method used to carbonate beer. Realising such a sophisticated technique, typically used by commercial breweries, was not the sort of thing that simple farmers would do, he tries to get out of it by saying ‘This technique wasn’t used frequently in farmhouse breweries (…) Later, this technique could have been spread when the farmhouse breweries became only breweries.’ Yeah right.

In a few instances, De Baets gives no reference to source material at all, for instance when claiming ‘each brewer had his own recipe’ or that some brewers also used wheat, oats, buckwheat and malted spelt. The same for the use of spices such as star anise, sage and coriander, or for his description of the developments in the 20th century. It’s not that I find all this particularly unconvincing, but it would have been nice if he had provided some sources. (Also, who would use spices in a beer that was then supposedly mainly appreciated for its sour taste and vinousness? But that’s another story.)

In a few instances, De Baets gives no reference to source material at all, for instance when claiming ‘each brewer had his own recipe’ or that some brewers also used wheat, oats, buckwheat and malted spelt. The same for the use of spices such as star anise, sage and coriander, or for his description of the developments in the 20th century. It’s not that I find all this particularly unconvincing, but it would have been nice if he had provided some sources. (Also, who would use spices in a beer that was then supposedly mainly appreciated for its sour taste and vinousness? But that’s another story.)

Markowski’s book and De Baets’ article in it have inspired people worldwide to drink and brew great beer, and that’s wonderful. But I feel that what De Baets writes is hardly representative of the actual history of saison or even of the Dupont-like variety from rural Hainaut. Clearly, De Baets took Dupont as a starting point and used only what seemed to confirm their story: saison as a farm beer. Think of this what you will, but I’ll just say this: I don’t mind if Belgian brewers engage in cherry picking, but only if it is to make kriek.

[1] Phil Markowski, Farmhouse ales. Culture and craftmanship in the Belgian tradition, Boulder (Colorado), 2004.

[2] Or the longer version of the real history: Flanders was a county; Hainaut was a separate county and never part of Flanders (nor were any of the other provinces that now constitute Wallonia, except for Walloon Brabant, which was only formed in 1995). Parts of Flanders were however conquered by France in the 17th and 18th centuries and are now part of the French departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais. Markowski somehow forgets to mention the most important part of historical Flanders: most of the old county of Flanders is now, of course, in the provinces of Eastern and Western Flanders in the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium (now also collectively known as Flanders, to complicate matters).

[3] Yvan De Baets, ‘A history of saison’, in: Markowski, Farmhouse ales, p. 96-127.

[4] http://lostbeers.com/what-was-a-19th-century-saison-really-like/

[5] Achille Latour, Les brasseurs et la bière, Nonette [1989], p. 6.

[6] Jules Cartuyvels and Charles Stammer, Traité complet théorique et pratique de la fabrication de la bière et du malt, Brussels / Liège 1879.

[7] Georges Lacambre, Traité complet de la fabrication de bières et de la distillation des grains, pommes de terre, vins, betteraves, mélasses, etc., Brussels 1851, p. 320-321.

[8] G. Vanderstichele, La brasserie de fermentation haute, Paris / Turnhout 1905, p. 280.

[9] Cartuyvels and Stammer, Traité complet, p. 413.

[10] http://lostbeers.com/eight-myths-about-lambic-debunked/ The Artois brewery in Leuven was using fresh hops in lambic as late as 1908 [EDIT: as late as 1914] (Brewing book ‘Nouveau Cornet’, Artois archives at the National Archives, Leuven).

[11] Lacambre, Traité complet, p. 320-321.

[12] Cartuyvels and Stammer, Traité complet, p. 412.

[13] Vanderstichele, Brasserie de fermentation haute, p. 286.

[14] Cartuyvels and Stammer, Traité complet, p. 412.

This is a great read—thanks! So am I to gather that you’re debunking the entire book (and the romantic story we’ve all been told)? Or is there still some truth to it, even if only in essence?

Thanks for your comment. I’d say that anything that concerns Dupont in the 20th century is more or less correct. It’s just that the farmhouse origin story doesn’t add up, and that all the 19th century and early 20th century brewing details come from sources that do not talk about saison (and certainly not about the farmhouse version, whether it existed or not).

Sorry, I must disagree, Cartuyvels talks about saison in 1873.

In the Bière de Liège section, “Pour préparer la bière de saison, qui ne se fabrique que dans la

saison favorable et ne se consomme que 4 à 6 mois après,sa

fabrication…”

Meaning In order to prepare Saison Beer that is only made during favorable season and that is consumed only 4 to 6 months after it’s fabrication

Excellent work!

Hi Roel, nice article! Do not hesitate to join this new group about European CRAFT beer news 🙂 and share with us your posts and tastings ! Thanks for your interest!

https://www.facebook.com/groups/2096849037295357

I’ve very much enjoyed your project of digging into primary source material to try and verify or debunk the marketing-driven myths about historical beers. Right on.

But but but. This is not your best work, and there’s quite a bit of ad hominem critique on De Baets and Markowski, ascribing intent to their actions based on your feelings (“I feel” is used to critique De Baets three times) in a way that kind of comes across as a personal vendetta. You might not intend it as such, but that’s how it reads.

If this is a historical project, it seems like it would be wise to refrain from so directly assuming you know the intent of De Baets and Markowski (at least you need to provide a much higher bar of evidence to prove that). If this is primarily a journalistic project, it seems you would have some kind of obligation to reach out to De Baets and Markwoski and ask for their thought process, particularly as there have been other cases where new evidence has emerged since Farmhouse Ales was published. And another personal opinion: the click-baity approach cheapens the value of what you’re contributing, which is otherwise quite valuable.

Hi Kyle, thanks for your thoughts. I try to keep my articles to the point, but I guess once in a while a personal note slips through. In any case, I have no beef with Phil Markowski or Yvan de Baets personally, and regardless of the historical errors I think they did a great job promoting a great beer style.

Have to agree with all of this. The really good information is partly obscured by the nasty tone. Is the purpose of this article to present a differing view of what Saisons were historically, or simply to denigrate the work of others? If the former, perhaps it should be revised.

Thanks Roel, really. This gets us closer to the truth I GUESS, and to understand better a couple of essential things. Here in Argentina, “saison” is any beer fermented with Belle Saison yeast strain and with fruit like peach, mango or passion fruit,that’s it, brewers just use the name as a fashion and to sell the beer. Even if you ask most of them, none has even read Markowski’s book or ever tried a Dupont, Fantôme or Blaugies. They just use the belle Saison strain, fermented at 18C al the way and that’s all. The rest is the farmhouse fairy tale everybody spreads to sell it. I Wish more brewers get friends with history books or blogs like yours. Or even get the guts to take out fruits and try, taste and work to perfect a recipe with the basic ingredients. Thanks again for making ir clearer.

Interesting post and claims, which I’m still processing.

The following footnote loses me, however:

“The Artois brewery in Leuven was using fresh hops in lambic as late as 1908 (Brewing book ‘Nouveau Cornet’, Artois archives at the National Archives, Leuven).”

I’ve spent a fair amount of time in the sub-basement of the National Archives in Leuven, and I know that brewing book “Nouveau Cornet” very well. I also know the books for the production of the Artois Breweries, the purchases and sales, and the Grands Livres for each year. I have many photos from all of those books here with me. None of them seem to list a “lambic” as such. Are you claiming that Peeterman is a lambic? Or that they made a “lambic” of some other kind? Can you please clarify?

In any case, the brewing logs in the book you mentioned do *not* list the years of the hops used. Just looking at the entry for 3 January 1901, for example, it says that the Peeterman brewed that day included 2700 kilos of wheat, 1300 kilos of malt and 38 kilos of hops. It does not say which provider or which year those hops are from. (I have plenty of photos that back this up.)

However, if you check the entries for “Houblon Haute-Fermentation” (meaning at the Nouveau Cornet brewery) in the Grand Livre, you’ll see that in the brewing year 1901, the Artois Breweries were using… Alost hops from the years 1895 and 1896. Meaning aged hops. I’ve got pictures if you want to see them.

To reiterate, I’m confused about what you’re trying to say here regarding “lambic” from the Artois Breweries.

And in terms of the claim that the Artois Breweries were using fresh hops for the beers produced in the Nouveau Cornet brewery around the turn of the century, the evidence I have says that’s wrong.

Hi Evan, thanks for your reaction.

I think we have not looked at the same brewing book.

I saw one simply called ‘Nouveau Cornet’ that includes the years 1907-1917. Next to white, Louvain and peeterman, it contains quite a few brews of lambic; it also includes Bavière and Pilsen for the war years.

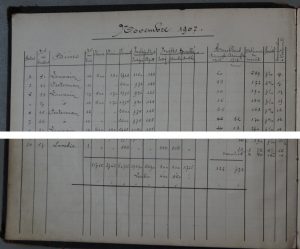

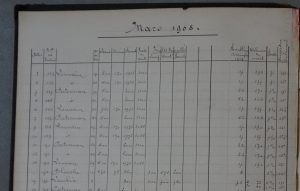

Here are entries for November 1907 and March 1908, where they used fresh hops for all the beers (from 7 November onwards):

There’s lambic as late as February 1914, when they used 1913 hops for lambic and 1912 hops for peeterman and Louvain:

Still, the presence of 1895 hops in 1901 (I photographed the same page, but hadn’t studied it in detail yet) is interesting, though I presume it was used for white beer and Peeterman, because as you say that year they weren’t producing lambic.

I really liked your blog on Czech brewers at Artois, by the way. I would like to delve into the (very chaotic) Artois archives further, but I haven’t found time to do so yet. In any case, there’s undoubtably much interesting stuff to be discovered there!

Wow, that’s wild. We are talking about different books. Mine even looks different, with a different layout.

Well, to establish what we do know, I’m sure there was no Artois “lambic” produced just a few years before that. The circa-1901 books list four different beers being produced in the Nouveau Cornet brewery: Peeterman, Blanche, Orge and Louvain. (In those books, Blanche is not the same as Louvain.)

NB: the brewery did have a habit of renaming beers. There’s one year where the beer they formerly called “Munich” becomes “Pilsen,” I believe (either that or their “Bock” becomes “Pilsen,” I can’t remember without looking it up) — at first the change is only in the local (Leuven) market, and then it happens to all markets. I’ll have to check my notes to find out which beer it was and when.

That leads me to think that there’s a chance that Artois might have simply renamed an existing top-fermented (but not spontaneously fermented) beer as “Lambic” at some point. That’s one possibility.

How do I put this? Even in 1908, this was not the most compulsively honest and transparent brewery out there. The stuff people complain today had analogues 100, 200 and 250 years ago.

Hi Evan,

I’m not so sure that the lambic at Artois is a renamed version of another beer, in the brewing book the grist seems quite distinct from the other beers. According to the old labels at jacquestrifin.be, Artois at some point made a ‘brune gueuze’ (from somewhere after 1906 until at least WWII), which is probably what the lambic was intended for.

In any case, the Artois archives are still full of surprises!

Roel,

Your research and “fact checking” should be most welcomed. There is so much more to be said, corrected and discovered about ancient beer.

However, the tone you are using reminds me something between presidential tweets and gossip magazines. “The incredible truth about X – you will be shocked!”. Wow. Very elegant. But whatever: I suppose it’s important, when one manages a website, to get as much clicks as you can to get it successful.

I personally see the evolution of knowledge more like an emulating team sport we all play together. And, -this is official- believe me, I will never claim I know everything on any subject related to beer. Making it myself since now almost 15 years professionally has forced me to be a bit more humble, as I’m touching its immense complexity every single day of my life. It helps me to know one thing for sure: I will never fully understand it. And I think it’s cool: it keeps the job fascinating.

Back to the subject, the sources are, indeed, extremely scarce and difficult to interpret for Saisons. My take on it is that it was indeed primarily and originally a rural type of beer, and that the scholars didn’t really want to write on rural things. Those guys were used to concentrate on what was happening in cities. The knowledge and money were there. The symbolic capital, as Bourdieu would have say, too. Who cares about the peasants, right?

So, written sources are very rare, but I consider oral testimony to fully be a valid source if of course different people are involved and not closely related to each other, and critical mind is applied. Add to this that you have to pay all the possible checking to be sure the people don’t have any “hidden agenda”, like trying to self-promote themselves or their companies. In that matter, I can assure you that Marc Rosier, who was at the time the CEO -although he would have never used that term- at Dupont brewery, is one of the most honest and genuine persons I have ever met in the industry. He would have never even think of making up stories for selling more beer. He was -as he sadly passed away earlier this year- the total opposite of a self-promoting and marketing person. I wish he could serve as an example for some people I know.

Oral testimony is a widely accepted source in Human Sciences in general, and History in particular. It’s actually considered being one of the best sources for recent history, except for the official documents. I’m extremely happy I could still get in touch and have long discussions with some of those old brewers before they passed or will pass away. I had the chance and privilege to speak to at least seven different old Saison brewers. They all told me the same story for the origin of it -in farms. Only two of them were related to Dupont by the way, and two of them (one Dupont-related, one other) openly hated each other, so they would have had no interest of telling a story that would have helped the other. But more generally: are you seriously claiming all those old Brewmasters were lying while you detain the truth about the beer they, their fathers and grandfathers, have been making all their life?? This would be nothing but contemptuous towards them, not talking about the arrogance behind it.

To add to this, I honestly don’t see anything one could not believe about that origin in farms. In the 18th and the19th Centuries, you had plenty of farming treatises being published. In most if not all of them you have a chapter on brewing. And not only homebrewing (for the family), but also sometimes at a level allowing the making of beer for a larger amount of people (the saisonniers, or summer workers for instance, and most probably some folks of the village).

In Hainaut, within the breweries that still exist, not only Dupont was a farm-brewery, but Dubuisson and Biset-Cuvelier (now Vapeur) also. It is documented.

Anyway, for you to know, even if I don’t have much time (unfortunately) to do lots of research and even less for writing and publishing anything at the moment -as I currently have one brewery to run and another, new one, to build- I continue reading, collecting sources and -how terrible!- talking to people. And everything I have found since I wrote the chapter in Farmhouse Ales in 2003 is still going in the exact same direction. When I was asked to write something for the book, it was originally not even meant to be a chapter, but I came with way more information than they expected, and it couldn’t have been cut without loosing too much of it. So, it finally became a chapter, thanks to Phil Markowski and the open mind of the publisher. But I was still in permanent pressure to make it as short as possible, as it was not planned to be in the book. And I had to fight for having footnotes written: they didn’t want it at first because they considered it would make the whole text to “heavy” to read for the public they were focusing on… I said that I could not write anything that would only look like personal claims and demanded the footnotes to be in. Phil Markowski -one of the best American brewers by the way- fought on my side. They finally accepted. You can see in the other books of the series that there are no precise footnotes. Just a general bibliography with books or articles that were used as sources. Not only all my sources are referenced, but also the very page in which you can find my quotations! You open the book, you find the quotation. Do you think it’s a way one would use if he wanted to hide anything? Really? If I demanded them to be included, it was for the precise reason that I wanted other researchers to have the possibility to criticize them! The idea was to start a work on the subject, hoping to complete it myself someday, and that others would complete it too. I have always been very transparent with it. In short, my entire work has been DESIGNED to be criticized!

Oh, and my original title for my text was “A historical approach of the Saison beers”. It means it was meant to be a formal essay. It’s the editor who choose to rename it “A History of Saison”. Still, it’s not “The” History of Saison, but “A” History of Saison. I didn’t want the title to sound definitive, as I knew for sure it’s a never-ending work in progress. And, yes, as a human creation, there must be mistakes in it. I only hope -for yourself- you realize there are errors in your writings too. It’s just inevitable. A last thing: the adjective “Farmhouse” is not mine. I don’t think it really makes sense (especially when a typical blue-collar/miner beer like Grisette is included in it). But it maybe gave a general idea of rustic techniques in a certain environment that helped the people to get a general picture, and maybe -yes- attract attention and, eventually, save a dying style of beer.

My entire approach was also explained (page 95) and transparent: my sources were oral testimonies, written records and a contextualization of the brewing techniques of the time, plus the tastings of bygone Saisons. So, when I quote some books that are not specifically talking about Saisons, I do it to explain, for instance, that the technique X was used at the time for making bière de garde, a family Saisons are part of, or was used in this specific region, and I use this to guess -yes, I’m guessing, as there are no precise sources and I was obviously not there at the time- that it is plausible that such a technique was used for the making of Saisons. I really don’t see what is wrong with such an approach, especially when a precise bibliography is written black on white.

You talk about misquoting and it’s very funny when you claim I said something I actually never said: “… proclaim that the Saisons of today are ‘similar to those of the past’”. Where did you find that one? I wrote: “Some beers brewed today are true authentic Saisons even if their brewers do not always call them by that name” (page 121). I say “some” at first, which means “not all”. And I’m talking mainly about Saisons from the post WWI evolution (like Blaugies or Dupont), although the mix-fermented ones I also mention relate more to the pre-WWI Saisons.

In addition, in short: grains: I said, because I was told by the old brewers, that it’s the other grains than malted barley (wheat, spelt, etc.) that were generally grown by the farmers. In the brewing books, the more you approach the end of the 19th Century, the more the brewing scholars recommend the sole use of malted barley for the making of bières de garde. Same for hops: they recommend better hops (from Bavaria and Bohemia when the brewers could get it for aroma, and Alost and Poperinghe for bittering, sometimes aroma) instead of the local ones. In Mons area, Hainaut, hops were cultivated. They had quite a bad reputation. They have been used by the brewers in the region, of course, including for the Grisette. Old hops were, in the real world, very frequently used, even if not recommended by the scholars -for good reason- except indeed for some specific styles of beer. One or two year hops badly kept easily smell like old hops. Spices: do you seriously think using spices in a sour beer has no influence on its flavor? Is that an argument? I maybe fell off a pedestal for you but what actually happened is that I fell off my chair when reading some of your brewing-related claims.

To come back to what seem to be an obsession for you, it is obvious that Saisons have also been made by other kind of breweries than farm-breweries, including village breweries-only and city breweries for a long time before 1900. I though it would have been something more of the late 19th Century (which I talk about, while you want the people to believe I claim “they hardly left the farmyard”, which is not true), and you found I think a publicity showing that a brewery of the city of Charleroi made a Saison before that. That’s good to know. I’m only happy when I see new information like that.

And, yes, of course, Saison is indeed synonym of “keeping”, de garde, provision, vieille, etc. I mention it. It could have been more developed. It is then obvious that the “Brune saison” you found a publicity of was simply a keeping dark ale. Makes me want to make one.

Something I strongly disagree with you is about the Saison de Liège: it is a style totally apart from the “other Saisons” -that were sometimes called the “Saisons de Wallonie”, a term found in the old literature but that is a little bit restrictive as there has been Saisons made in Flanders too. (Should we call them “countryside Saisons”? -you will get mad…) I, indeed, am claiming that with force! The reasons are, among others, its poor attenuation, that is very well documented (even in the De Clerck, who speaks about an attenuation between 50 and 60%) and a quite precise recipe (although, as for every style of beer, there has been an evolution with the time – so far I have found three different main recipes for it, related to three different periods; there might be more), while the countryside Saisons offer way more possibilities recipe-wise. Those latter Saisons were obviously beers highly attenuated, due to the wild yeasts necessarily involved in their fermentation back in the days, and old brewers confirm that.

A last thing: there exist only one monograph about “Saison”, written in 1907. But it’s specifically on Saison de Liège, not about the “countryside Saisons”. The book is entirely dedicated to the promotion of new, more modern, methods for making the very Saison de Liège.

To summarize, if I had to rewrite that chapter now, it would be longer and more nuanced, with some new additions, more sources, and there would certainly be a chapter on what is for me the main myth about Saison: yeast! But the description of the essence of the fabrication of these beers would still be the same.

This is your website. By definition you will have the last word on it. Cool. I will not start a debate here anyway. I have more to say about some of your claims but I don’t have nor the time nor the desire to do it: not only I strongly dislike the ego battles, but more importantly the first tanks of our new brewery are arriving in a few weeks and I have to prepare them a nice nest.

Yvan De Baets

Hi Yvan,

Thanks for your detailed reply. I strongly feel that while writing my blog post, at several times I have gone in a direction that my website shouldn’t go, and I do think that I could have handled this in a better way. I’m sorry if this has offended you. Also, the title was indeed intended to grab people’s attention, but I didn’t realise in time how much it resembles today’s cheap ‘clickbait’ found online all too often.

It’s great that you’ve provided some background information on how the article was created. (It’s what I originally asked you, but regrettably I grew too impatient to ask you again.)

I hope that we can go foreward from here. There is indeed a lot still to be learned about saison and I also see a lot of gaps that still need to filled up.

That said, even though you provide references for a lot of your sources (for which I’m grateful), I still feel you were retro-fitting historical information to make it say something it never did. My main problem with your article is, that you’re approaching saison history from the wrong end: the sources shouldn’t confirm what you already think you know, in my opinion they should tell you where to go.

I am perfectly willing to believe (as I already stated in my article) that what Mr. Rosier and his colleagues told you was a genuine testimony of what saison was in that region at that particular time. I’m sure it more or less happened as they told you.

But I’ve done enough oral history myself to know that it has its limitations: how far do these testimonies go back? How are they corrobated by other sources? And how does practice in early 20th-century rural Hainaut fit in with saison history as a whole?

Without a doubt, many Belgian breweries have been connected to farms in the past. Dupont, Dubuisson, Biset-Cuvelier, but also Palm, Bosteels and others. But it’s hard to say how exactly this fits in with saison history. There seems to be some overlap, but it’s clear to me that saison and farm beer were not always necessarily the same thing.

By the way, you do say that ‘several breweries still produce [saisons] and fortunately these saisons are similar to those of the past.’ It’s on the first page of your article.

I agree that saison de Liège poses a problem. Is it an ancestor of current Hainaut saison? Did the two develop separately? Did they influence eachother? It seems that by WWI, at least in a few places spelt had been replaced by barley in Liège saison (this was the case at Maastricht in 1913). Hainaut saison is absent from 19th century brewing literature, so why does it appear on post-WWI bottle labels (plenty of examples on jacquestrifin.be, an excellent website) , apparently as an all-malt luxury beer? Is there a missing link that can tie Liège and Hainaut saison together? I hope to find some answers to this.

I’m not familiar with the 1907 book on Liège saison you mention, it sounds very interesting. Can you tell me the title and where I can find it? Also, you mention ‘saison de Wallonie’, I haven’t come across this term yet, maybe you can tell me where to find it?

In any case, yes I would be interested in tasting a ‘brune saison’ if you made one.

Keep up the good work with your brewery.

Best regards,

Roel

Oral sources are valid and important, and often contain information that no other sources do because it was never written down. But – it’s a big but – people have fallible memories and they often also tell stories that they have heard from someone else, at which point they become much less useful. This is the trap that Michael Jackson (and also others such as Greg Noonan) fell into when he repeated the charming and romantic stories that brewers had told him. Once people such as Martyn Cornell and Ron Pattinson compared these tales with actual historical documents, it turned out that a lot of what Jackson wrote down was folklore handed down through the brewery, rather than verifiable fact.

Thank you Yvan De Baets!

[…] been a shock wave hammering those writing about the history of saison. You see, Roel Mulder has shared his thoughts of a fact-checking mission he undertook on the “2004 book Farmhouse ales, and […]

Roel,

You might want to amend the bit where you write that Phil Markowski “thinks that Wallonia and the French departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais were ‘once collectively known as Flanders’”, and state that “this is a laughable assertion to anyone who even remotely knows anything about Belgium”.

The medieval County or Fiefdom of Flanders certainly did encompass parts of modern-day Wallonia (i.e Hainaut) and Northern France. When this historic county ceased to exit in 1795, it was because it became part of France itself! – although admittedly that did not last very long.

Markowski is undoubtedly correct geographically, although his use of the term “Kingdom of Flanders” is questionable (not incorrect, necessarily, but questionable).

Martin

Well, to be fair, re-reading my copy of Markowski, he does overstate how much of modern Wallonia was once part of Flanders at one point in the text. I suspect it’s poor editing rather than poor geography or history.

So, for example, note that his p.3 reference mentions The Netherlands. So when he writes, on p.15, that “a national border seperates the region of Wallonia in Belgium and the French Departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais, the area once collectively known as Flanders”, perhaps we should understand him to mean, “a national border seperates the region of Wallonia in Belgium FROM the French Departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais, the area once collectively known as Flanders”.

And his point, surely, is to remind us that the people of these borderlands have shared more, culturally, than has separated them?

Maybe both of you have a lot of truth in what you write. To me it makes sense that farmers, like brewers probably only wrote what they had to. Brewers have to fill out brew logs, perhaps farmers did not.

So it may well be that the written evidence is tied into the brewer’s story. The rural Saison may well have little evidence beyond a few oblique mentions in brewing books and in oral testimonies.

Perhaps Saison was also more widely used term as originally thought. Maybe it is like Porter – brewed in London to what everyone thinks is the standard recipe, but in the country it was a different beast. After all, Saison just means ‘season’ it is not a more tightly defined term like IPA (in the historical sense). But even IPA grew to be a looser name. Both IPA and Porter also developed considerably over the years and ended up very different in their end states – which are still developing, just like Saison.

Perhaps the testimonies of a rural based brewer contemporary brewer and the log books from a town brewer of 100 years ago will naturally be at odds.

Anyway, just my 2 cents…

[…] med Farmhouse Ale. Vad som är den korrekta historiska beskrivningen har det diskuterats om främst här. Jag kommer inte göra en historisk djupdykning kring ölstilen. Är man intresserad av det […]