Bavarian beer from Breda

An aspect of Dutch beer history I hadn’t dealt with sufficiently so far, is ‘Beijersch’ (which means, in old Dutch spelling, Bavarian) beer. From the middle of the 19th century onwards, it replaced the old Dutch beer types, especially after the 1868 beer law made its production a lot cheaper. Often this Beijersch beer has simply been equated to pilsener, but that’s not right. Pils came to the Netherlands only in 1876, and initially sold only in modest quantities. So what kind of beer was Beijersch?

An aspect of Dutch beer history I hadn’t dealt with sufficiently so far, is ‘Beijersch’ (which means, in old Dutch spelling, Bavarian) beer. From the middle of the 19th century onwards, it replaced the old Dutch beer types, especially after the 1868 beer law made its production a lot cheaper. Often this Beijersch beer has simply been equated to pilsener, but that’s not right. Pils came to the Netherlands only in 1876, and initially sold only in modest quantities. So what kind of beer was Beijersch?

On page 102 my book has a recipe for a ‘Hollandsch Beijersch’ (‘Dutch Bavarian’) beer from 1866, adapted to the old legislation, which means it doesn’t use infusion (raising the mash temperature step by step, by boiling a part of the wort). That was a blond beer. But the actual Beijersch made by the post-1868 industrial Dutch breweries was something else. My fellow beer historian Ron Pattinson, who had been browsing the Heineken archives, assured me that their Beijersch was a brown beer. So it was time for me to look through some records myself again. And I already had a lot of data from the town of Breda, in the South of the Netherlands.

The history of De Drie Hoefijzers (‘Three Horseshoes’) goes back a long way. In 1628 one Dielis Peeters van den Kieboom bought the ‘Den Boom’ (‘The Tree’) brewery in Breda, and changed its name to ‘De Drije Hoeffijsers’. The site is now a busy intersection in Breda’s old city centre, near the popular brewpub De Beyerd. Although the brewery kept referring to 1628 as their year of origin, the original company on that spot dated from 1538.[1]

Anyway, in 1807 De Drie Hoefijzers was bought by J.N. Smits and that family would run it for another century and a half.[2] At that moment, Breda had eight breweries. Over the course of the 19th century, the traditional Dutch brewing industry declined, something that had been going on for a few centuries. The Smits family was among the first in the province of North Brabant to successfully switch to working on an industrial scale, after German examples and with German bottom-fermenting beers.

In December 1886 a building permit was granted for a brand new steam beer brewery just outside the city, where already six years before a new malthouse had been built. A German brew master was hired, Kurt Weber from Höhnstadt (near Leipzig, Germany). The brewing installation, ice machine included, was supplied by Maschinenfabrik Germania from Chemnitz (also near Leipzig). The goal was to make ‘both foreign and Breda type beers’.[3]

In December 1886 a building permit was granted for a brand new steam beer brewery just outside the city, where already six years before a new malthouse had been built. A German brew master was hired, Kurt Weber from Höhnstadt (near Leipzig, Germany). The brewing installation, ice machine included, was supplied by Maschinenfabrik Germania from Chemnitz (also near Leipzig). The goal was to make ‘both foreign and Breda type beers’.[3]

Okay, but what kind of beers are we talking about? The brewing records have been preserved from 1886 to 1925, and there is some post-WWII material.[4] The records start with the last year and a half of the old brewery on Boschstraat in the centre, where apparently only ‘orge’ (French for ‘barley’) beer was made. The beer’s original gravity varied between 1041 and 1049, sometimes rice was added, and they used hops from Aalst in Belgium.[5]

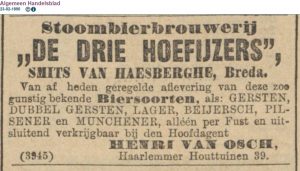

19 August 1877 was the last brewing day in the old brewery. However, on July 25 they had already made the first brew in the new building on Ceresstraat. Right away, they didn’t write down the gravity in the familiar four-digit density figures anymore, but in the completely different Balling scale. Also, the Belgian hops were largely replaced with Bavarian and English hops within a year. De Drie Hoefijzers was doing very well: within five years production doubled from 18464 hectolitres (in 1886) to 37719 (in 1892) and it would continue to increase. Especially the relatively cheap lager beer was popular, while they also made a small amount of Beijersch and some pilsener. The top-fermenting ‘gerste’ (barley) or ‘Hollandsch’ beer was slowly fading away. Interestingly, they also made a ‘colour’ beer, with 50% ‘Farbmalz’ (colour malt). Apparently it was used to give some extra colour to some of the other beers. It made up around 1% of total production. Perhaps it was used to make Münchener (Munich type) beer, which certainly was advertised, but doesn’t feature in the brewing records.

19 August 1877 was the last brewing day in the old brewery. However, on July 25 they had already made the first brew in the new building on Ceresstraat. Right away, they didn’t write down the gravity in the familiar four-digit density figures anymore, but in the completely different Balling scale. Also, the Belgian hops were largely replaced with Bavarian and English hops within a year. De Drie Hoefijzers was doing very well: within five years production doubled from 18464 hectolitres (in 1886) to 37719 (in 1892) and it would continue to increase. Especially the relatively cheap lager beer was popular, while they also made a small amount of Beijersch and some pilsener. The top-fermenting ‘gerste’ (barley) or ‘Hollandsch’ beer was slowly fading away. Interestingly, they also made a ‘colour’ beer, with 50% ‘Farbmalz’ (colour malt). Apparently it was used to give some extra colour to some of the other beers. It made up around 1% of total production. Perhaps it was used to make Münchener (Munich type) beer, which certainly was advertised, but doesn’t feature in the brewing records.

From 1892 a comprehensive report has been preserved of the brewing process for both gerste and Beijersch beer.[6] The gerste beer was brewed with top fermentation, as well as the blending beer and the table beer, however the typically German infusion method, mentioned above, was used. It wasn’t particularly heavy, 9.3 degrees Balling, which is the equivalent of about 4% ABV. Interestingly, the gerste was blended with ‘sour blending beer’ which was stored in a separate building on Pasbaan street (just around the corner from today’s De Beyerd café). There it could quietly go sour biologically, in big barrels. In a dedicated ‘Old beer cellar’ underneath the malthouse on Ceresstraat it was blended with the fresh gerste beer.[7]

From 1892 a comprehensive report has been preserved of the brewing process for both gerste and Beijersch beer.[6] The gerste beer was brewed with top fermentation, as well as the blending beer and the table beer, however the typically German infusion method, mentioned above, was used. It wasn’t particularly heavy, 9.3 degrees Balling, which is the equivalent of about 4% ABV. Interestingly, the gerste was blended with ‘sour blending beer’ which was stored in a separate building on Pasbaan street (just around the corner from today’s De Beyerd café). There it could quietly go sour biologically, in big barrels. In a dedicated ‘Old beer cellar’ underneath the malthouse on Ceresstraat it was blended with the fresh gerste beer.[7]

It would be interesting to delve further into this one day. In the 19th century Breda knew several of these ‘old’ beers like Breda’s Oud and Breda’s Provisiebier. Of the latter, I have a recipe with various spices, but I don’t know how long it was kept and whether it was blended.

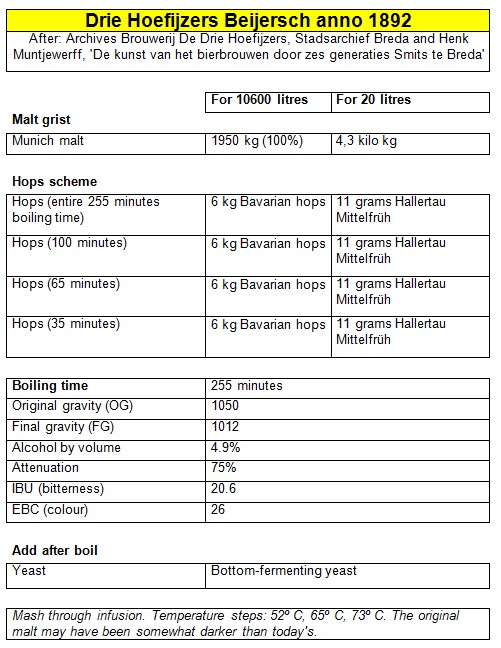

Anyway, then there is the Beijersch beer. In the 1892 description (when it made up 5% of total production) Moravian and Hungarian malt was used, but that doesn’t tell us much about the colour. With a brew in December 1895 however, there is mention of the use of ‘Malz Münchener Art’ (Munich style malt), and likewise in 1896 and 1899. Munich malt is a relatively dark malt type that still contains enough enzymes to use it as a base malt. How dark? In 1897 the brewing book mentions a ‘Pfälzer’ malt (from Palatinate in Germany) that has been kilned at 120 degrees Celsius. By current standards, that would be pretty dark: today, Munich malt is usually kilned at only around 105 degrees.[8]

That means that in Breda Beijersch beer was made with a quite dark malt. Actually, they didn’t brew a lot of it: Beijersch had already given way to the cheaper lager. This popular type was produced with appropriately called lager malt. How dark that malt was? I don’t know, in any case it was not the same as pilsener malt, because in Breda they had that as well and it was used, again appropriately, only to make pilsener.

That means that in Breda Beijersch beer was made with a quite dark malt. Actually, they didn’t brew a lot of it: Beijersch had already given way to the cheaper lager. This popular type was produced with appropriately called lager malt. How dark that malt was? I don’t know, in any case it was not the same as pilsener malt, because in Breda they had that as well and it was used, again appropriately, only to make pilsener.

All in all, the Beijersch beer is a nice, malty brew that I wouldn’t mind tasting. About what happened to the Drie Hoefijzers brewery later on , that’s another story for another time.

[1] D.C.J. Mijnssen, ‘De bierbrouwerij “De Drie Hoefijzers” te Breda’, in: Jaarboek De Oranjeboom 25 (1972), p. 93-98.

[2] Henk Muntjewerff, ‘De kunst van het bierbrouwen door zes generaties Smits te Breda (1807-1968), een industrieel erfgoed’, in: Jaarboek De Oranjeboom 57 (2004), p. 231-318, p. 250-252.

[3] Muntjewerff, ‘Kunst van het bierbrouwen’, p. 269-273, 310.

[4] Stadsarchief Breda, Archief Firma F. Smits van Waesberghe / Brouwerij De Drie Hoefijzers, inv. no. 797-804.

[5] In the brewing books, the gravity figure seems to contain one zero too many, so for what is indicated there as ‘1004.8’, I took 1048. Probably, they measured in Belgian degrees (in this case 4.8) and simply added 1000.

[6] Muntjewerff, ‘Kunst van het bierbrouwen’, p. 307-309.

[7] Muntjewerff, ‘Kunst van het bierbrouwen’, p. 275.

[8] Hans Michael Eßlinger, Handbook of Brewing. Processes, technology, markets, Weinheim 2009, p. 163.

I was thrilled to read this. In the last century I was a summer intern there as part of a business school exchange program with Tilburg University. Breda Bier was the first beer I ever tasted, but not the last! The Smits family were exceptional hosts.

Hello. I read with interest your essay about the history of Dutch beer, hoping to see some reference to my maternal ancestor’s Breda brewery . It was called, I believe, “Van Reuth’s Beer”. I understand it was sold all over Europe in the 18th century, and that the brewery itself was sold by my great-grandfather’s grandfather, Josephus Norbertus van Reuth. The proceeds of that sale were then used to open another family business in Breda called “Van Reuth and Van Gils Banking and Manufacturing Company” with satellite branches in Nymegen and two other towns in the Netherlands. Do you have any info. re van Reuth’s Beer? Please reply by email to my address below. Many thanks. (Mrs.) Sue Douthit, 44 Ferry Road, Doylestown, PA 18901-5013, U.S.A.