Crabbeleer, a historic beer returns… or does it?

In June 1847 several newspapers featured a remarkable story. For instance, the Leydse Courant (from Leiden in Holland) told its readers: ‘Gent, 22 June. A new or rather old type of beer is brewed here now, which is called crabbeleire and which was highly regarded by the citizens of Gent in the 15th century… Mr. Van der Haagen has retrieved the recipe and is now supplying tasty, foaming crabbeleire to several innkeepers.’[1] Nice, a lost beer brought back to life, that’s how we like it. But what was the story behind it?

In June 1847 several newspapers featured a remarkable story. For instance, the Leydse Courant (from Leiden in Holland) told its readers: ‘Gent, 22 June. A new or rather old type of beer is brewed here now, which is called crabbeleire and which was highly regarded by the citizens of Gent in the 15th century… Mr. Van der Haagen has retrieved the recipe and is now supplying tasty, foaming crabbeleire to several innkeepers.’[1] Nice, a lost beer brought back to life, that’s how we like it. But what was the story behind it?

The Gazette van Brugge (from Bruges) was already a bit closer to the source. It read: ‘Gent, 24 June. Since a few days, everybody in this city talks about a type of beer, called Crabbeleer, that existed in the 1300s and was conceived to compete with the brown beers of that age, called Leeuwaerd and Clauwaerd.’[2]

The most comprehensive version of the story was published on 23 June 1847 in a magazine called De Gentschen Mercurius, in an article simply titled ‘Crabbeleer’. It takes the anonymous author a lengthy bombastic introduction before finally getting to the point: ‘Crabbeleer, then, is a beer, and a beer that… had the honour of appearing on Jacob van Artevelde’s table, and that of Philips van Artevelde and his brave companions… The Leliaerts, addicted to France, drank wine; Jacob van Artevelde and his comrades, who had ‘Flanders the Lion’ as their slogan, drank beer…’[3]

You may start to feel dizzy at this point. Jacob who? Leliaerts? Flanders the Lion? But in 19th century Flanders, everybody would know what you were talking about. Jacob van Artevelde (ca. 1290-1345) once was a merchant in Gent and leader of a revolt against the king of France. At that moment the French, who also ruled over Flanders, were at war with England, Gent’s most important trade partner. It’s where they got the wool for their sizeable textile industry. Such a fighter for freedom was naturally seen as an inspiring figure in later centuries, especially in his native Gent, which still proudly calls itself ‘city of Artevelde’. In 1863, a towering statue of this people’s hero was inaugurated on Vrijdagmarkt square. A people’s hero who apparently was fond of a good pint.

You may start to feel dizzy at this point. Jacob who? Leliaerts? Flanders the Lion? But in 19th century Flanders, everybody would know what you were talking about. Jacob van Artevelde (ca. 1290-1345) once was a merchant in Gent and leader of a revolt against the king of France. At that moment the French, who also ruled over Flanders, were at war with England, Gent’s most important trade partner. It’s where they got the wool for their sizeable textile industry. Such a fighter for freedom was naturally seen as an inspiring figure in later centuries, especially in his native Gent, which still proudly calls itself ‘city of Artevelde’. In 1863, a towering statue of this people’s hero was inaugurated on Vrijdagmarkt square. A people’s hero who apparently was fond of a good pint.

‘Leliaards’ was the name of the 13th and 14th-century Flemish supporters of France. Their enemies were the Liebaards, supporters of Flemish interests, who were also known as Leeuwaards of Klauwaards. And according to the 1847 article, those last two names were also beer types that were popular among fighters for the Flemish cause. ‘But the Leeuwaerd and the Clauwaerd were brown beers… and there was an even greater wish for white beer… One of the brewers of Gent, one who worked laboriously and who as a true patriot befriended Van Artevelde, by the name of Hendrik Goethals, wanted to meet that demand…’ A certain Jan de Crabbe, an important magistrate ‘steadily visited the inns’ where Goethals’ beer could be found, and in his honour the beer was called ‘crabbeleer’.

Still according to the 1847 article, the crabbeleer remained a renowned beer for over two centuries, and naturally it was especially popular among the brave warriors of Flanders, until it died out during the Eighty Years War (1568-1648). But as luck would have it, there now was a brewer in Gent, a certain Charles Vander Haeghen, who had dug up the recipe and was reviving this once famous beer. Gent drinkers who had tasted this new 1847 crabbeleer all admitted that ‘in goodness, virtue, taste and flavour it is equal to the best Hoegaarden beer, and can compete with any beer in stoneware bottles.’ The article concluded with the happy coincidence that the beer had been introduced right before the start of the yearly funfair and supplied a list of Gent pubs where it was available. ‘Long live the crabbeleer, in saecula saeculorum!’

Yeah, great. But as these things go: when such a historic tale is just a bit too euphoric, I get suspicious. And luckily, I was not the only one. It turns out the anonymous author, who only signed his article as ‘S………’ was in fact a certain Théodore Schellinck (1797-1867), a Gent journalist and amateur historian. Soon I discovered more about in him in a 1898 book by archivist Victor Van der Haeghen, with the promising title Mémoire sur des documents faux relatifs aux anciens peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs flamands (Treatise on false documents concerning old Flemish painters, sculptors and engravers).[4]

Yeah, great. But as these things go: when such a historic tale is just a bit too euphoric, I get suspicious. And luckily, I was not the only one. It turns out the anonymous author, who only signed his article as ‘S………’ was in fact a certain Théodore Schellinck (1797-1867), a Gent journalist and amateur historian. Soon I discovered more about in him in a 1898 book by archivist Victor Van der Haeghen, with the promising title Mémoire sur des documents faux relatifs aux anciens peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs flamands (Treatise on false documents concerning old Flemish painters, sculptors and engravers).[4]

Archivist Van der Haeghen (as far as I know not related to the aforementioned brewer) had noticed that in Gent, of all places, there were circulating a tad too many remarkable old documents that had something odd about them. For instance, someone had been tinkering with the books of the old painters’ guild, that dated from the 16th century but to which an unknown 19th-century perpetrator had added a number of mock Medieval pages. Another case was the 16th-century Gent painter and writer Lucas d’Heere, whose book of biographies of famous Dutch painters had long been lost. Long lost yes, but in the 19th century all sorts of alleged quotations from this book seemed to emerge everywhere. Hmmm.

It is the tragedy of us critically-minded historians that we lose so much time debunking nonsense spread deliberately or undeliberately. Van der Haeghen describes how said falsifications had found their way into serious publications, because people trusted these sources or simply didn’t know any better. And if I myself would only get ten euros for every time I have to read somewhere that beer king Cambrinus was the same person as duke John of Brabant!

Further on, Van der Haeghen’s book gets to the Gent journalist Théodore Schellinck, author of the article on crabbeleer. Who was he? Another source describes Schellinck as ‘barren-bodied, brown-skinned, his shoulders raised high and his head bent over,’ with skinny legs and curbed toes. ‘Barber nor hairdresser have ever made much money on him. Moreover, he warped his already unappealing face in strange twists, from steadily chewing tobacco.’ In short, un unusual man, who was said to have had to renounce from a project of setting up a newspaper in Hasselt because he had been caught visiting a brothel there.[5]

During his lifetime Schellinck wrote for various newspapers, but history was his hobby. He catalogued the archives of various towns, churches and guilds, and he wrote serialised historical fiction. It was however not beneath him to invent whole genealogies out of thin air for well-paying wealthy families. Another ‘literary con game’ was a book on the history of eyeglasses and eye diseases in Gent, filled with fabricated historical facts and quotations on how important the opticians of Gent supposedly had been. This book too managed to fool serious historians for decades. In a similar way Schellinck brought all sorts of fabrications on historical painters into circulation. Van der Haeghen does not actually acknowledge it, but for the falsifications mentioned earlier Schellinck also seems to be the prime suspect.

Anyway, this colourful Schellinck was the man behind the article on crabbeleer, undoubtedly at the request of the brewer who wanted to have an original way of marketing it. It wouldn’t be the last time a brewer tweaks history a bit (or more) with an eye on sales…

So what’s the real deal with crabbeleer? This beer type actually existed, we learn from an article on the Gent brewing industry by Paul de Commer.[6] It just existed later than Schellinck claimed. In the early 16th century, Gent knew only small beer and double beer. In 1522 two new ‘double’ beers were introduced, called ‘crabbelaer’ and the slightly stronger ‘clauwaert’. As the 16th century progressed, the crabbelaer morphed into a simple, rather weak beer, while in 1573 clauwaert spawned a new, even stronger version, the double clauwaert. At that time, crabbelaer made up about 50% of total Gent beer production, and about 43% around 1604. After that, it probably slowly died out. A recipe has not been preserved, but there is no particular reason to assume it was a white beer.

So what’s the real deal with crabbeleer? This beer type actually existed, we learn from an article on the Gent brewing industry by Paul de Commer.[6] It just existed later than Schellinck claimed. In the early 16th century, Gent knew only small beer and double beer. In 1522 two new ‘double’ beers were introduced, called ‘crabbelaer’ and the slightly stronger ‘clauwaert’. As the 16th century progressed, the crabbelaer morphed into a simple, rather weak beer, while in 1573 clauwaert spawned a new, even stronger version, the double clauwaert. At that time, crabbelaer made up about 50% of total Gent beer production, and about 43% around 1604. After that, it probably slowly died out. A recipe has not been preserved, but there is no particular reason to assume it was a white beer.

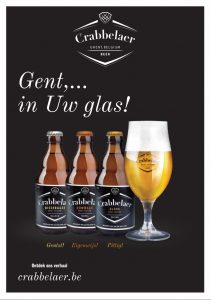

So there you have it… Jacob van Artevelde, hero of the people, never drank crabbeleer. The beer with the same name that was introduced in 1847 didn’t last long either, the self-satisfied marketing story notwithstanding. Yet nothing is ever forgotten: after some googling, I learnt that a few years ago a Gent-based contract brewery revived crabbelaer, using it as a name for their blond and triple. Accompanied by the correct story by Paul de Commer. So I guess we’ll have to drink that, then. And if you really want to honour Van Artevelde there still is the Huyghe brewery, which has been producing a beer named after him since the 1980s.

[1] Leydse Courant, 25-6-1847.

[2] Gazette van Brugge 25-6-1847.

[3] ‘Crabbeleer’, in: Gentschen Mercurius 23-6-1847.

[4] Victor Van der Haeghen, Mémoire sur des documents faux relatifs aux anciens peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs flamands, Gent 1898.

[5] Daniël Van Ryssel, ‘Vergeten Gentse schrijvers. Théodore Schellinck (Gent 1797 – Gent 1867). Journalist, scherpzinnig en verbeeldingrijk vervalser, schrijver’, in: Ghendtsche tydinghen volume 43 nr. 2 (March 2014), p. 149-151.

[6] Paul de Commer, ‘De brouwindustrie te Gent, 1505-1622’, in: Handelingen der Maatschappij voor Geschiedenis en Oudheidkunde te Gent, XXXV (1981), p. 81-114 and XXXVII (1983) p. 113-171.

could I obtain a recipe for crabbeleer beer?

I would like to make this beer. But I need the recipe. Rob.