Beer riots in 19th century Brussels

Climate protests, angry farmers, yellow vests: mass protests are all over the news at this moment. So far, I haven’t seen beer lovers on the barricades, but even this used to happen once in a while. In 19th century Brussels for instance.

Climate protests, angry farmers, yellow vests: mass protests are all over the news at this moment. So far, I haven’t seen beer lovers on the barricades, but even this used to happen once in a while. In 19th century Brussels for instance.

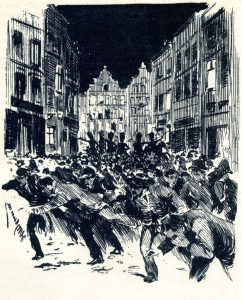

On Sunday evening 16 September 1855, around eight o’clock, a crowd gathered at the Grand-Place in Brussels in front of the Le Renard café, located in the monumental building of the same name, and the adjacent Rue de la Tête d’Or. What was the problem? For years, the city’s popular beer, faro, had been sold at 12 centimes a litre.[1] Even during the food scarcity of 1846, the landlords of Brussels had managed to maintain this price level. Now, grain prices were on the rise again. In 1854, there had been several riots about the price of bread. This time, the pub owners wanted to increase the price of a faro by two centimes. The increase had been announced on Saturday 15 September, and about a quarter of the pub owners of Brussels intended to adhere to the new price level. They were soon going to regret that.[2]

That Sunday evening, several windows and glasses had been smashed, and the police had already intervened. By midnight however, uproar was on the rise again. There were some disturbances inside the café, and the owner had to be evacuated. Several people were arrested.[3] On Monday morning there was another gathering of people. Three rioters were arrested: a tinsmith from Ixelles, a chair maker and a salesclerk. That evening, the gatherings were even bigger, but the police were present as well. At Le Renard, a window pane was hit by a brick and by midnight, all pubs on the Grand-Place were evacuated.[4]

That Sunday evening, several windows and glasses had been smashed, and the police had already intervened. By midnight however, uproar was on the rise again. There were some disturbances inside the café, and the owner had to be evacuated. Several people were arrested.[3] On Monday morning there was another gathering of people. Three rioters were arrested: a tinsmith from Ixelles, a chair maker and a salesclerk. That evening, the gatherings were even bigger, but the police were present as well. At Le Renard, a window pane was hit by a brick and by midnight, all pubs on the Grand-Place were evacuated.[4]

In the end, the ‘baes’ (boss) of Le Renard gave in: the price for a glass of faro was reinstated at its former level of 12 centimes. Quickly, the news was spread around town, and it wasn’t long before another crowd of workmen gathered: but this time to cheer and sing and have a pint. Other pub owners followed the example. The ‘émeute du faro’ was over.[5]

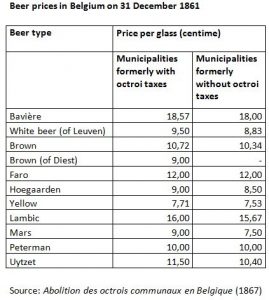

Interestingly, faro already was quite expensive of its own. At 12 centimes for half a litre (then, a ‘pint’ really was a pint in Belgium, not the miserable 0.25 litre you get nowadays when ordering a ‘pintje’) it was one of the most expensive beers in the country. In Belgium, a Hoegaarden white beer generally cost 8.5 to 9 centimes, a white beer of Leuven 9 to 9.5, a Peeterman set you back 10 centimes, a brown 11 and an uytzet 10.5 to 11.5 centimes. Only lambic was more expensive: 16 centimes.[6]

Even by 1872, the price of faro was still the same old 12 centimes. Then, a few landlords in the Belgian capital toyed the audacious idea of again raising the price to 14 centimes, this time in connection with the high prices of coal used in the brewery. Again, some ‘lamentable scenes’ followed and the intervention of the police was needed to restore the public order. Remarkably, by then the price of lambic had risen to 25 centimes. It would seem that since 1855, along with some monetary inflation, the gravity of faro itself had diminished to some extent. Or at least the price difference with lambic had greatly increased in less than twenty years.[7]

Even by 1872, the price of faro was still the same old 12 centimes. Then, a few landlords in the Belgian capital toyed the audacious idea of again raising the price to 14 centimes, this time in connection with the high prices of coal used in the brewery. Again, some ‘lamentable scenes’ followed and the intervention of the police was needed to restore the public order. Remarkably, by then the price of lambic had risen to 25 centimes. It would seem that since 1855, along with some monetary inflation, the gravity of faro itself had diminished to some extent. Or at least the price difference with lambic had greatly increased in less than twenty years.[7]

All in all, 19th century Brussels saw beer riots only twice, as far as I’ve been able to find.[8] Later, these of course turned into a nice tall story: in the early 20th century, some newspapers chuckingly looked back, and pretended the people of Brussels only took to the streets when beer prices were affected. Which is nonsense of course: bread riots were much more common, especially in the 1840s and 1850s. Thy did however trace a protest song which allegedly was popular back in 1855. It translates as:

‘If bakers want to raise prices again

‘If bakers want to raise prices again

Let them do it while they can

But that wonderful faro beer

That was the only thing that made us cheer…’[9]

In the end, with the advent of modern bottom-fermented beer and high-quality gueuze, faro lost its status of being the people’s drink, especially after the First World War. Luckily, it does still exist: in a good Brussels pub, you can still order one. Just don’t forget that nowadays it will cost more than just 12 centimes… which in today’s money would be less than one eurocent.

[1] Some accounts mention a price of ‘6 cents’. At that time in Belgium, oddly, the name ‘cent’ meant ‘2 centimes’.

[2] Journal de Bruges 19-9-1855; Gita Deneckere, Sire, het volk mort. Sociaal protest in België (1831-1918), Antwerpen 1997, p. 121-122.

[3] L’Indépendance belge 18-9-1855.

[4] L’Indépendance belge 19-9-1855.

[5] La Presse 20-9-1855.

[6] Abolition des octrois communaux en Belgique. Documents et discussions parlementaires, Tome 1, Brussel 1867, p. 572.

[7] Burgerwelzijn 5-10-1872; Le Temps 21-9-1872.

[8] The poster ‘Histoire du faro et du lambic à travers les âges’ by Edgard Tytgat from 1935 mentions a faro riot in 1842, but I haven’t been able to trace it.

[9] Le soir 31-1-1901; Journal de Bruxelles 18-10-1902; Le Bruxellois 13-7-1915.

Leave a Reply