The memoirs of Jef Lambic

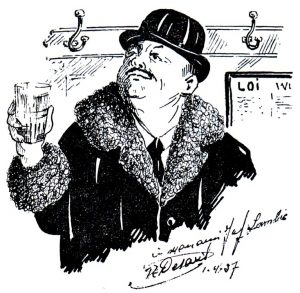

The Pottezuyper. The Brommelpot. The Kwaksalver. Krott & Compagnie.[1] They’re just a few of the many types of pub-goers described by a mysterious writer from Brussels in his Mémoires de Jef Lambic. This little book, published in 1958, is all about beer, pubs, and especially ‘zwanze’, a type of humour particular to Brussels. And all this in a late 19th century setting of gaslight and horsecars. It’s an odd book that has to be dissected on multiple levels, because: who actually wrote it, and what of it is true?

The Pottezuyper. The Brommelpot. The Kwaksalver. Krott & Compagnie.[1] They’re just a few of the many types of pub-goers described by a mysterious writer from Brussels in his Mémoires de Jef Lambic. This little book, published in 1958, is all about beer, pubs, and especially ‘zwanze’, a type of humour particular to Brussels. And all this in a late 19th century setting of gaslight and horsecars. It’s an odd book that has to be dissected on multiple levels, because: who actually wrote it, and what of it is true?

Two litres of lambic he would drink daily, a litre of faro and a litre of table beer. Over the course of his life, he must have gulped down 160,000 litres of Brussels beer in total, Jef Lambic calculates. Still, he lived to be 91 years old, if we are to believe his memoirs. And that’s exactly the question with this little book. As I want to know everything about the history of Belgian beer, I read anything I can find. Brewery histories, brewing books, biographies, regional histories, hop chronicles. But Les mémoires de Jef Lambic is in a category of its own. Is it fiction, is it real, can we learn anything from it or is it just a big pile of fabrications?

1958 was the year that Brussels hosted the Expo ’58 world fair, which carried Belgium into the nuclear age. However, that same year a publisher in that same city, ‘La technique belge’, released Les mémoires de Jef Lambic.[2] According to the introduction, it comes from a manuscript found during demolition works in the Rue des Capucins in Brussels, in an empty beer barrel.[3] The pages were wrapped in pink garter belts and supposedly were written by one Jef Lambic, born the first of April (!) 1860, and died in 1951. As an old man, the author apparently had written down his memories of the merry pub life of Brussels during his youth.

1958 was the year that Brussels hosted the Expo ’58 world fair, which carried Belgium into the nuclear age. However, that same year a publisher in that same city, ‘La technique belge’, released Les mémoires de Jef Lambic.[2] According to the introduction, it comes from a manuscript found during demolition works in the Rue des Capucins in Brussels, in an empty beer barrel.[3] The pages were wrapped in pink garter belts and supposedly were written by one Jef Lambic, born the first of April (!) 1860, and died in 1951. As an old man, the author apparently had written down his memories of the merry pub life of Brussels during his youth.

His father was a brewer in that same Rue des Capucins, he himself became a clerk at the office for mortgage conservation, but that didn’t keep him from going to the pub on a daily basis, to enjoy beer and the company of the ladies. Years later, with a certain nostalgia, he looks back to a time when a glass of faro cost 12 cents, that Brussels still knew 300 beer blenders and that there was one pub for every 13 households. On New Year’s Eve, landladies would make their ‘calibabou’: warm lambic with a secret mix of sugar, rum, cinnamon, clove and whipped eggs. An innocent time of mischief and excursions to the countryside in springtime. A countryside now swallowed up by the city.

His father was a brewer in that same Rue des Capucins, he himself became a clerk at the office for mortgage conservation, but that didn’t keep him from going to the pub on a daily basis, to enjoy beer and the company of the ladies. Years later, with a certain nostalgia, he looks back to a time when a glass of faro cost 12 cents, that Brussels still knew 300 beer blenders and that there was one pub for every 13 households. On New Year’s Eve, landladies would make their ‘calibabou’: warm lambic with a secret mix of sugar, rum, cinnamon, clove and whipped eggs. An innocent time of mischief and excursions to the countryside in springtime. A countryside now swallowed up by the city.

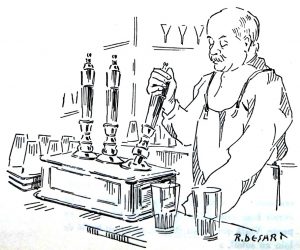

A time when Brussels sang and danced, in high hats and crinoline, as Jacques Brel put it. A time that the ‘baes’ (boss) could pour his beer cold from the tap, because a bar of ice had been placed inside the pump. The ‘meekes’ (girls) would bring the beer, preferably a strong lambic, to your table. It was a time when the French language came to dominate Brussels for good, although many ‘Brusseleirs’ would still speak the old Flemish dialect at home and throw in a few words of it into their French every now and then. The street signs showed overlong French translations of the original Flemish names, like the ‘Vestje’ that became ‘Rue du Petit Rempart’ (Little Rampart Street), the ‘Warmoesberg’ (Vegetable Mountain) now was ‘Rue Montagne aux Herbes Potagères’, and so on.

A time when Brussels sang and danced, in high hats and crinoline, as Jacques Brel put it. A time that the ‘baes’ (boss) could pour his beer cold from the tap, because a bar of ice had been placed inside the pump. The ‘meekes’ (girls) would bring the beer, preferably a strong lambic, to your table. It was a time when the French language came to dominate Brussels for good, although many ‘Brusseleirs’ would still speak the old Flemish dialect at home and throw in a few words of it into their French every now and then. The street signs showed overlong French translations of the original Flemish names, like the ‘Vestje’ that became ‘Rue du Petit Rempart’ (Little Rampart Street), the ‘Warmoesberg’ (Vegetable Mountain) now was ‘Rue Montagne aux Herbes Potagères’, and so on.

The weird way the manuscript was supposedly ‘found’, the improbable name and the day of birth (the 1st of April) all strongly suggest that Jef Lambic was a fictitious person. However, many anecdotes related in the book do seem to have some truth to them. A few stories that could be checked easily, such as Hawaiian king Kalakaua’s visit to a Brussels pub, or the existence of the mysterious comical society of the Agathopèdes, are all in some way based on real events.[4] The same goes for the practical joke in the form of an auction catalogue full of very rare books that lured a flock of collectors to the carnival city of Binche, which actually took place.[5]

Jokes and mischief, that’s what they liked in Brussels. Les mémoires de Jef Lambic is packed with ‘zwanze’: an intelligent form of humour, that in this book mainly takes the guise of all sorts of pranks. A nice example is the chamber pot that was kept for years on a shelf in a pub in the Rue aux Choux called Le Diable au Corps. A chamber pot that was only used when out-of-towners had ventured into the café. Once these were seated, the pub’s ‘baes’ would secretly take the chamber pot from its shelf and fill it with blonde beer and a few pieces of gingerbread. Next, the serving girl would hide the pot under her large black dress, go to the out-of-towners’ table and with a lot of fuss she would ‘discover’ the pot under the table. At which the landlord would cry: ‘Och arme! Our menneke has been playing in the pub again!’ And he would pretend to yell at his wife: ‘Our little boy has left his pispot among our clients’ legs again!’

Jokes and mischief, that’s what they liked in Brussels. Les mémoires de Jef Lambic is packed with ‘zwanze’: an intelligent form of humour, that in this book mainly takes the guise of all sorts of pranks. A nice example is the chamber pot that was kept for years on a shelf in a pub in the Rue aux Choux called Le Diable au Corps. A chamber pot that was only used when out-of-towners had ventured into the café. Once these were seated, the pub’s ‘baes’ would secretly take the chamber pot from its shelf and fill it with blonde beer and a few pieces of gingerbread. Next, the serving girl would hide the pot under her large black dress, go to the out-of-towners’ table and with a lot of fuss she would ‘discover’ the pot under the table. At which the landlord would cry: ‘Och arme! Our menneke has been playing in the pub again!’ And he would pretend to yell at his wife: ‘Our little boy has left his pispot among our clients’ legs again!’

By then, the pub regulars knew which game was being played. One of them would join the conversation, and grab the chamber pot from the serving girl’s hands, growling: ‘What’s this? We don’t let anything go to waste here!’ And he would take a large gulp from the pot, after which he would pass it to the next regular, who after another gulp would yell: ‘Voilà, they don’t serve you this in a restaurant!’ But by then, the out-of-towner usually had already run out of the door, hiccupping…

By then, the pub regulars knew which game was being played. One of them would join the conversation, and grab the chamber pot from the serving girl’s hands, growling: ‘What’s this? We don’t let anything go to waste here!’ And he would take a large gulp from the pot, after which he would pass it to the next regular, who after another gulp would yell: ‘Voilà, they don’t serve you this in a restaurant!’ But by then, the out-of-towner usually had already run out of the door, hiccupping…

So, Les mémoires de Jef Lambic gives a fascinating peek into a lost world. That leaves us with the question: who wrote it and how much of it is true? As the book was illustrated by Brussels artist Robert Desart (1898-1981), it has been assumed that he is also the writer, for instance by the website lambic.info, which has based its logo on a drawing in the book. But I’m not so sure: Desart wasn’t a writer, at least not of this kind of hilarious anecdotes, as far as I know. It is telling that most of his drawings do not match what is happening in the text. Also, Desart was a bit young to have witnessed the era that is evoked so vividly and in detail here. This is also true for a few of his pals who did write a lot about Brussels, such as Louis Quiévreux (1902-1959) and Jean d’Osta (1909-1993).

My suggestion would be to have a closer look at Curtio, pseudonym of the prolific Brussels writer George Garnir (1868-1939), a ‘maître-zwanzeur’ who demonstrably did experience 19th century pub life.[6] Not in the least because… several of his texts have been included verbatim in Jef Lambic. Curtio’s descriptions of typical pub-goers like the brommelpot (grump), the frucheleer (a merry busybody) and ‘Krott et Compagnie’ (a family with whining kids visiting a pub) were published as far back as 1906-1907 in several books and newspapers.[7] Jokes about a ‘piswijf’ (female restroom attendant) or about the Rue de Merode (a street in Brussels named after a war hero, but interpreted as named after nightclub dancer Cléo de Mérode) feature both in Jef Lambic and in Curtio’s work.[8] What’s more, Curtio himself, or at least his real-world persona of George Garnir, has a cameo in Jef Lambic‘s book![9]

My suggestion would be to have a closer look at Curtio, pseudonym of the prolific Brussels writer George Garnir (1868-1939), a ‘maître-zwanzeur’ who demonstrably did experience 19th century pub life.[6] Not in the least because… several of his texts have been included verbatim in Jef Lambic. Curtio’s descriptions of typical pub-goers like the brommelpot (grump), the frucheleer (a merry busybody) and ‘Krott et Compagnie’ (a family with whining kids visiting a pub) were published as far back as 1906-1907 in several books and newspapers.[7] Jokes about a ‘piswijf’ (female restroom attendant) or about the Rue de Merode (a street in Brussels named after a war hero, but interpreted as named after nightclub dancer Cléo de Mérode) feature both in Jef Lambic and in Curtio’s work.[8] What’s more, Curtio himself, or at least his real-world persona of George Garnir, has a cameo in Jef Lambic‘s book![9]

There is of course one problem: when Jef Lambic was published in 1958, George Garnir had been dead for almost twenty years. But perhaps… the publication of the book itself was an act of ‘zwanze’? Who knows, maybe Garnir had already prepared the manuscript, but had stipulated that it could only be released years after his death, with a few brief references to current affairs (post-war Belgian prime minister Paul-Henri Spaak gets a name check) squeezed in? Or was there a post-war anonymous editor who compiled several of Curtio/Garnir’s texts and knitted them together? Or did the bulk of the text flow from another pen and did they just plagiarise Garnir (perhaps with permission) in a few places? Have Quiévreux and d’Osta worked on this?

It remains a mystery. As it should, in the case of a good zwanze. In the end, Jef Lambic is first and foremost a well-played prank.

[1] ‘Pot guzzler’, ‘Grumpy pot’, ‘Quack’, ‘Krott and Company’ (see below).

[2] Robert Desart (illustrations), Les mémoires de Jef Lambic, Brussels 1958.

[3] As the book Jef Lambic is in French, and as French is more widely understood worldwide, I ‘ll stick to the French names of streets etc. in this article. In the Dutch version, I used the Dutch/Flemish names.

[4] Jef Lambic, p. 46, 70-73; Journal de Bruxelles 29-07-1881; https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soci%C3%A9t%C3%A9_des_agathop%C3%A8des

[5] https://www.canvas.be/canvas-curiosa/de-fortsas-hoax

[6] Curtio, Le petit brusseleir illustré, Brussels 2010, p. 7.

[7] Reprinted several times, under names like Zievereer Krott & Cie Architek. Baedeker de physiologie Bruxelloise, and as a compilation under the name Le petit brusseleir illustré. Examples in newspapers: Le soir 7-2-1907, 16-3-1907; Le petit bleu du matin 16-4-1907. See also: https://vimeo.com/88982244

[8] Jef Lambic, p. 49, 83; Curtio, Le petit brusseleir illustré, p. 10, 91-92.

[9] Jef Lambic, p. 87.

Leave a Reply