Fact check: where did gruit occur?

Recently someone added me to a gruit chat group on Facebook, called ‘The Gruit Guild’. That meant many pictures of brews and of people picking herbs out on the heath. After all, gruit was a herb mix added to beer in the Middle Ages, before people started using hops. But recently, someone asked a historical question, so I was happy to interfere. The question was: where did gruit actually occur? A fact check!

Recently someone added me to a gruit chat group on Facebook, called ‘The Gruit Guild’. That meant many pictures of brews and of people picking herbs out on the heath. After all, gruit was a herb mix added to beer in the Middle Ages, before people started using hops. But recently, someone asked a historical question, so I was happy to interfere. The question was: where did gruit actually occur? A fact check!

Lately I had already been studying gruit, for an article in the Brewery History journal. There, I summarised the basic facts, and debunked a few odd claims made by others (read the article here).[1] And now at The Gruit Guild someone wanted to know: where exactly did gruit exist? Because this is what American beer historian Richard Unger writes about it, in his book Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance from 2004:

‘The state had the power to control the use of gruit, which was, by far, the most popular additive for ale throughout the early and the high Middle Ages in most of northwestern Europe. Brewers commonly used it in the Low Countries, the lower Rhine Valley, Scandinavia, and even in northern France. The term, in its many forms, appears all the way from Bayonne on the Bay of Biscay, along the coast, and in coastal regions to Gdansk in Poland.’[2]

Gruit from Basque Country to Poland? That made me frown a little. So what do you do in such a case? You look at the footnote to check where Unger got it from. And, ouch. His source turned out to be a German article from 1908, by one Aloys Schulte. Schulte talks about the various herbs gruit contained, one of which was bog myrtle (myrica gale). But was exactly does Schulte write? ‘The herb bog myrtle… surfaces near Biarritz and Bayonne, and follows the North Sea coast until beyond Danzig.’[3] In other words, Schulte is talking about where the herb bog myrtle occurs in nature. That means Unger didn’t read it properly: he thought not bog myrtle, but gruit, the herb mix to be put in beer, occurred in that vast area!

Well yeah, that’s how things become a mess. But then, if gruit didn’t occur all the way from Bayonne tot Gdansk, where did it? In Scandinavia? Not according to the Norwegian (?) guy who asked me on Facebook. Northern France? Unger’s sources say hardly anything on that country. So that’s no help either.[4]

There is some danger of confusion about the definition of gruit. It has been established that in various areas, including Scandinavia, France and England, herbs were added to beer in the Middle Ages. In England this was optional, there ale could be brewed without any flavouring whatsoever.[5]

Herbs in beer occurred more often, but when do we speak of gruit? We do when it’s mix of various herbs on which the local authorities had a monopoly, which resulted in an artificially high price. In that way it was a de facto tax on beer. The composition of gruit could be secret and could differ from place to place. It has been argued, not successfully in my opinion, that gruit wasn’t a flavouring agent made of herbs, but a grain porridge that speeded up mashing, or a wort syrup that could serve as a yeast starter. The ease with which gruit was eventually replaced by hops from the fourteenth century onwards, seems to prove that gruit, like hops, really was added mainly for its taste.[6]

That brings us back to the question: where did gruit really occur? In his 1955 book, Dutch engineer Gerard Doorman gave a wonderful survey of what the sources tell us about gruit. Next, Hans Ebbing made a critical analysis of Doorman’s work in his thesis Gruytgeld ende hoppenbier. By combining these publications, Schulte’s article mentioned above and some more literature, we get an idea of where gruit was known. [7]

That gives us these places, sorted by which country they’re in nowadays:

| The Netherlands | Belgium | Germany | France | |

| Aardenburg Alkmaar Alphen Ameide Amersfoort Amsterdam Arnhem Breda Delft Den Bosch Deventer Doesburg Dordrecht Goor Groenlo Haarlem Harderwijk Helmond Kampen |

Leiden Lochem Maasbommel Maastricht Nijmegen Ootmarsum Ouddorp Rhenen Roermond Rotterdam Utrecht Venlo Vollenhove Wijk bij Duurstede Woudrichem Yde Zaltbommel Zutphen Zwolle |

Bruges Diest Dinant Tournai Fosses-la-Ville Gembloux Gent Herentals Huy Ieper Leuven Lier Lombardsijde Liège Nieuwpoort Nivelles Rodenburg Sint-Truiden Turnhout |

Aachen Beckum Bocholt Dortmund Duisburg Emmerich Goch Köln (Cologne) Kempen Kleve Mönchengladbach Monheim Münster Neuss Osnabrück Ratingen Rees Tecklenburg Vreden Wesel |

Cambrai Crespin |

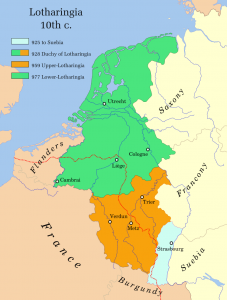

Thus, gruit occurred roughly in the Low Countries, the lower Rhine area in Germany, and Westphalia. Interestingly, this area more or less corresponds to Lower Lorraine, which by the time gruit was first mentioned (from 974 onwards) was a German duchy. Flanders (mostly part of France) and Westphalia (part of Saxony) however weren’t part of it. As far as we know, in the Low Countries gruit disappeared during the 15th century, in westernmost Germany often only in the 16th century, and Osnabrück and Tecklenburg are supposed to have known gruit beer into the 17th century.[8]

Thus, gruit occurred roughly in the Low Countries, the lower Rhine area in Germany, and Westphalia. Interestingly, this area more or less corresponds to Lower Lorraine, which by the time gruit was first mentioned (from 974 onwards) was a German duchy. Flanders (mostly part of France) and Westphalia (part of Saxony) however weren’t part of it. As far as we know, in the Low Countries gruit disappeared during the 15th century, in westernmost Germany often only in the 16th century, and Osnabrück and Tecklenburg are supposed to have known gruit beer into the 17th century.[8]

The name ‘gruit’ is interesting too. In the part of the gruit area where Germanic languages were spoken, it was called ‘gruit’, ‘grut’ or ‘grüssink’, the latter being a mostly Westphalian term for the beer that was made with it. In the area where Romance languages were spoken, its name was usually ‘materia’, ‘maceria’ or ‘maire’. It is tempting to connect the word ‘gruit’ to Dutch words like ‘grut’, ‘grutten’, ‘gort’ and ‘gruis’ (or English words like groat, grit, grits, grind, etc.), which indicate a finely ground matter. ‘Materia’ then simply means ‘matter’ or ‘substance’.[9]

It is however confusing that in most of this period Latin was the only language used for writing. Latin, originating from the wine-drinking Southern part of Europe, did not have a word for gruit and so writers came up with the word ‘fermentum’, after which often was added the word in the local language as an explanation (for those who known Latin: for instance ‘fermenti cervisiarum, quod maiera vulgo dicitur’, ‘fermentatae cervisiae, quod vulgo grut nuncupatur’).[10]

It is however confusing that in most of this period Latin was the only language used for writing. Latin, originating from the wine-drinking Southern part of Europe, did not have a word for gruit and so writers came up with the word ‘fermentum’, after which often was added the word in the local language as an explanation (for those who known Latin: for instance ‘fermenti cervisiarum, quod maiera vulgo dicitur’, ‘fermentatae cervisiae, quod vulgo grut nuncupatur’).[10]

The word ‘fermentum’ comes from the Latin ‘fermentare’ which originally meant ‘to ferment’. Because of this, it has been argued that Medieval people thought gruit stimulated fermentation. I don’t really believe that. I’m inclined to think that in Medieval Latin ‘fermentare’ could also simply mean ‘to brew’; after all, ‘brewing’ is another thing that Latin didn’t really have a word for. For instance, in 1364 emperor Charles IV wrote of a ‘novus modus fermentandi cervisiam’, or a ‘new method of brewing beer’, which was with hops. And of hops we are certain that it wasn’t seen as something that stimulated fermentation. Thus, for a Medieval person ‘fermentum’ simply meant ‘brewing substance’.[11]

The next time, I’ll have a look at an even more burning question: what did gruit actually contain? Because it is much less of a riddle than some people claim.

[1] R. Mulder, ‘Further notes on the essence of gruit: an alternative view’, in: Brewery History 169 (2017), p. 73-76.

[2] Richard W. Unger, Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Philadelphia 2004, p. 30.

[3] Aloys Schulte, ‘Vom Grutbiere. Eine Studie zur Wirtschafts- und Verfassungsgeschichte’, in: Annalen des historischen Vereins für den Niederrhein insbesondere die alte Erzdiözese Köln, nr. 85 (1908), p. 118-146, here p. 120.

[4] J. Deckers, ‘Recherches sur l’histoire des brasseries dans la région mosane au moyen âge’, in: Le moyen âge 1970, p.445-491, here p. 458.

[5] Raymond van Uytven, Geschiedenis van de dorst. Twintig eeuwen drinken in de Lage Landen, Leuven 2007, p. 63; Ian S. Hornsey, A history of beer and brewing, Cambridge 2003, p. 318-320.

[6] Vgl. Mulder, ‘Further notes’.

[7] G. Doorman, De Middeleeuwse brouwerij en de gruit, Den Haag 1955; Hans Ebbing, Gruytgeld ende hoppenbier. Een onderzoek naar de samensteling van de gruit en de opkomst van de Hollandse bierbrouwerij van circa 1000-1500, thesis Universiteit van Amsterdam 1994; Schulte, ‘Vom Grutbiere’; Raymond Van Uytven, ‘Haarlemmer hop, Goudse kuit en Leuvense Peterman’, in: Arca Lovaniensis, jaarboek 1975, p. 334-351; Deckers, ‘Brasseries dans la région mosane’; Paul de Commer, ‘De brouwindustrie te Gent, 1505-1622’, in: Handelingen der Maatschappij voor Geschiedenis en Oudheidkunde te Gent, XXXV (1981), p. 81-114, here p. 86. In France Schulte also mentions Abbeville, but that looks like a reference to a building torn down in 1795, which belonged to the Lords of Gruuthuse from Bruge, and not an actual gruit house.

[8] Mulder, ‘Further notes’ p. 74-75; Schulte, ‘Vom Grutbiere’, p. 140-141.

[9] Schulte, ‘Vom Grutbiere’, p. 144-146; Ebbing, Gruytgeld ende hoppenbier, p. 23, 25.

[10] Ebbing, Gruytgeld ende hoppenbier, p. 10, 28.

[11] John Beckmann, A History of Inventions and Discoveries, volume IV, Londen 1814, p. 337.

Excellent article, thanks for the details. Now I’m glad someone added me to that FB group too!