Fact check: the Vandervelde Law

A Belgian law from 1919 aimed at combating alcohol abuse, is credited with creating the heavy Belgian beers we now know so well: the dubbels, the tripels, the Duvels. But is it true? Time for a fact check.

A Belgian law from 1919 aimed at combating alcohol abuse, is credited with creating the heavy Belgian beers we now know so well: the dubbels, the tripels, the Duvels. But is it true? Time for a fact check.

This is what well-known Belgian beer writer Jef van den Steen has to say about it, in connection with the rise of ‘heavy’ trappist beers after the First World War:

Undoubtedly, also the Van der Velde (sic) law plays a role: it came into effect on 29 September 1919, prohibiting consumption, sale and supply (even for free) of alcoholic spirits in all places accessible to the general public. Thus, it stimulates the sale of heavy beers: in 1921 [the abbey of] Westmalle starts brewing a dark ‘dubbel’…[1]

The suggestion is clear: because in Belgium gin was banned from the pubs, monks started brewing heavier beers. And other brewers too, because in his book Abdijbieren Van den Steen repeats his claim:

One of the important consequences of this law is the rise of ‘bières de forte densité’: in 1921 Westmalle creates the dubbel, in 1923 Moortgat launches the Victory Ale, which will later become Duvel. In Brussels the breweries come up with double bock…[2]

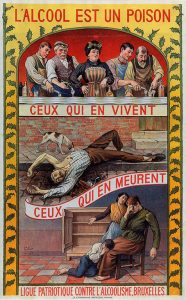

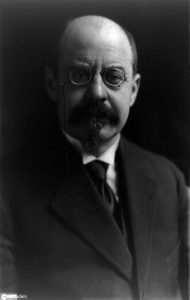

What law are we talking about here? It’s the alcohol law that came into effect on 29 August (not September) 1919. It was conceived by Emile Vandervelde, minister of Justice and a socialist in heart and soul. And a passionate anti-alcohol activist. At some point, I’ll be looking at the anti-alcohol craze that raged through Europe and the United States since around 1850, but one thing was clear for the teetotallers of those days: it was the poor workman that had to keep his hands of the bottle. If members of the upper class wanted to get sloshed on gin, wine and champagne, that was quite all right. As long as the working class didn’t get themselves drunk.

Anyway, just after the First World War, the temperance movement saw their chance. In the United States, where alcohol was completely prohibited, but also in Belgium: on 15 November 1918 Vandervelde pushed through a law that implied a total ban of alcoholic spirits. No sale, no production, no exports, no imports. After some protests, the law was slightly diluted and the result was the famed 1919 Vandervelde law. The sale of spirits in pubs was prohibited, but for consumption at home Belgians were still allowed to buy it in shops, but only in quantities of at least two litres (!). Thus the Belgian caught in the streets with one bottle was considered a criminal, but with two bottles, there was no problem.

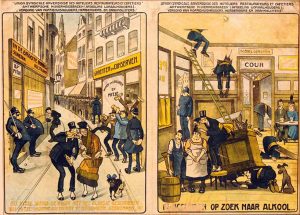

The idea was of course that poor people could not afford to buy such a big quantity at once, especially not since excise had quadrupled too. The workman could not get drunk anymore, the rich man could carry on drinking at home as he had always done, and everything was as it should be again. Naturally, pub and restaurant owners weren’t pleased. They had wonderful posters printed showing the malpractices and injustices that were to be expected: fines for pubs, drunkards at the off-licence. And of course a considerable black market and ditto production, with all the dangers associated with it.

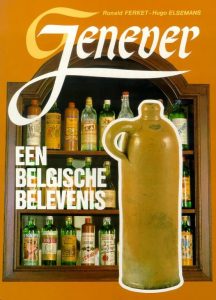

But now the main questions: did the new law have the desired effect on the sale of genever? And: did the ban on spirits encourage Belgians to start drinking heavier beers, as Van den Steen claims? To answer the first question: in any case the sale of genever dropped because of the law. Consumption in Belgium in 1919 was as roughly half of the pre-war level .[3] But now the alcohol content of beer. Did the Belgians start to drink tripels in huge numbers, just to get the desired amount of alcohol? Um, no. In 1930 the average alcohol content of Belgian beer was 3.36%. That was hardly more than the 3.29% that it had been in 1900. And that’s roughly where it stayed: in 1940 it was at 3.40%, hardly a significant rise.[4] At the same time, consumption of beer in Belgium as a whole dropped. While in 1900 a Belgian would drink 220.5 litres of beer a person a year, in 1930 that was 201.6 litres and three years later only 155 litres.[5]

It seemed such a nice story: Vandervelde wanted to combat genever, but created heavy beers. In reality, beers like dubbel and tripel remained rare, and only gained popularity after 1950. Did the Vandervelde law do nothing for Belgian beer culture? Of course it did. In other countries, such as the Netherlands, beer consumption dropped even more during the 1930s. In Belgium beer undoubtedly profited from the absence of distilled beverages in the pub. But the beers didn’t get heavier, like Van den Steen claims.

After the Second World War, Belgian beer of course slowly did become heavier. But it would be wrong to credit this to the Vandervelde law. For one thing, low-alcoholic table beers were outcompeted by upcoming soft drinks, causing the average alcohol content of beer to rise. Most heavy Belgian alcohol bombs however only date from the 1980s: La Chouffe, Kwak, Verboden vrucht, Kasteel, Delirium Tremens and all other Gulden Draaks, Moeder Overstes, Fantômes etcetera came into being only then. And what happened to the consumption levels of alcoholic spirits in Belgium? It was rising too in those years![6] The entire idea that genever and beer in Belgium are like communicating vessels is simply not true.

On 1 January 1984 the Vandervelde law was finally abolished. About time, because allegedly the ban on spirits in pubs had been massively violated for years: a great many ‘wittekes’ was being handed to the patrons from under the bar.[7] From now on, the Belgian genever culture could go hand in hand again with beer. Genever café De Vagant in Antwerp for instance has a selection of over 200 genevers from about forty Belgian genever and liqueur distillers. So, when in Belgium and tired of beer…

[1] Jef van den Steen, Trappist. Het bier en de monniken, Leuven 2003, p. 17. (my translation)

[2] Jef van den Steen, Abdijbieren. Geestrijk erfgoed, Leuven 2004, p. 17. (my translation)

[3] Eric Van Schoonenberghe et al., Jenever in de Lage Landen, Brugge 1996, p. 152; Raymond van Uytven, Geschiedenis van de dorst. Twintig eeuwen drinken in de Lage Landen, Leuven 2007, p. 255.

[4] Van Uytven, Geschiedenis van de dorst, p. 251.

[5] Van Uytven, Geschiedenis van de dorst, p. 251.

[6] Van Uytven, Geschiedenis van de dorst, p. 281.

[7] De Telegraaf 7-7-1983, 7-1-1984; Limburgs dagblad 14-1-1984.

An excellent article. I’d become very suspicious of this story, especially after I saw numbers for average Belgian beer gravities in the 20th century.

I can vouch for genever often being sold under the counter in Belgian pubs. I saw it a couple of times on my early trips to Belgium.