Brasserie à Vapeur: Belgium’s last steam brewery

B ack in February I visited the wonderful Brasserie à Vapeur in the small village of Pipaix in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. Going there is quite an experience: because of the monumental preserved brewery, and because of the uniquely festive atmosphere a brewing day has there.

ack in February I visited the wonderful Brasserie à Vapeur in the small village of Pipaix in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. Going there is quite an experience: because of the monumental preserved brewery, and because of the uniquely festive atmosphere a brewing day has there.

Originally, the Brasserie à Vapeur (which literally means Steam brewery) was the Biset-Cuvelier brewery, a small enterprise run by the family of the same name, that also ran an adjacent farm. In 1895, they had a small steam engine installed to power various aspects of their brewhouse. An important sign of modernity for that time, especially for such a small village (though it wasn’t even the village’s only brewery, because Pipaix is also home to Dubuisson, known for its Bush beer). The last brewer, Gaston Biset (1898-1985), knew his son wouldn’t take over the business from him, so he never modernised the place, and left it largely in the state it was already in. By the 1980s, he was still brewing his Biss amber and some saison, with the aid of his steam engine.

It was at this stage that Jean-Louis Dits knocked on the door. History teacher in a local high school and home brewer, but also running a small trade in local beers. Having worked with Gaston Biset for some time, he learned in 1984 that Biset, well over eighty years old, was closing the brewery. Would Dits perhaps be interested in buying it? Jean-Louis and his wife decide to take the risk.

That’s how the old brewery was saved – otherwise, Biset’s children probably would have had the place demolished. Instead, Dits and his wife decided to keep it running, on a small scale. One brewing day per month, open to the public. Sadly, Dits’ wife Sitelle was killed an accident with the steam kettle in 1990. Jean-Louis Dits now runs the brewery with his new wife Vinciane.

As I said, a brewing day at Brasserie à Vapeur is quite an experience. It starts at 9 AM, when the 12 horsepower steam engine sets in motion the stirring mechanism in the mash tun. Simultaneously, malt and water are added. A wonderful sight to see a type of brewhouse that I only knew from black-and-white illustrations in old, well-thumbed books, in full operation. The steam is not heated by coal anymore, but by fuel oil, which is quicker and cheaper.

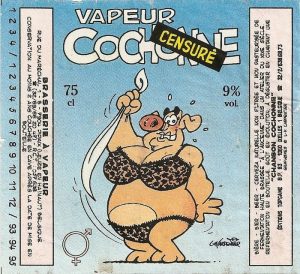

That day, they were making 4,000 litres of Vapeur Cochonne, one of their stronger beers at 9% ABV, a beer conceived by Dits and not an historical recipe. In fact, with this installation, it’s possible to make 12,000 litres of much weaker beer, but that probably wouldn’t be as popular now. In a way, the brewing process at Brasserie à Vapeur is a compromise between 19th and 21st century brewing. Dits sends steam through the mash to heat it; heating it with only water would yield a much weaker beer.

|

|

|

|

The ingredients are local: the malt comes from Beloeil, 15 km away, while the hops are from Warneton near the French border. The yeast was actually cultivated from samples scraped of the wall in the brewery 30 years ago. It is now commercially available.

Meanwhile, the party has started in the tasting room. For Jean-Louis and Vinciane, brewing is also about hospitality.

That morning, there were quite a lot of visitors: a local hiking club, a few tourists from Flanders and a guy from the Wallonian heritage board, because they are considering registering the brewery as an historical monument. By noon, most of the visitors had adjourned to the tasting room in the old farm building on the other side of the road. There, a wonderful meal was served, and of course a lot of beer. Especially the members of the hiking club, all well over sixty years of age, were having a great time, singing songs and cracking jokes.

In fact, though the meal is not free, Jean-Louis and his helpers are doing it all for fun. He has kept his job as a teacher all along, and only since a few years the brewery is just about breaking even. But what a way to keep the old brewery alive!

In the meantime, a few local lads emptied the mash tun of its spent grains, while the beer was boiling upstairs. Some spices and sugar are added. Their most popular beer is the Vapeur Cochonne, with its risqué labels involving pigs, designed by Louis-Michel Carpentier, a cartoonist from Brussels known for his ‘Du côté de chez Poje’ comic strip. In fact, Carpentier was dropping by that very afternoon, and it was nice to talk to a (much more successful) fellow beer comic writer (I make a much more crudely drawn comic strip for Dutch Bier magazine). To me, Carpentier’s labels are typical of microbreweries that started out in the 1980s and 1990s: tongue-in-cheek and usually involving an animal or a woman with naked breasts; and Carpentier even managed to combine the two.

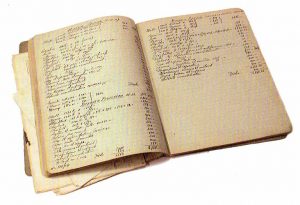

A completely different label is reserved for the Saison de Pipaix, which was already produced by the previous owners. A 6% ABV saison spiced with ginger, pepper, lichen, orange peel and star anise, it’s the continuation of the saison that Dits claims was already made here when the brewery started in 1785. The recipe has been recorded in a little black book, that Gaston Biset gave to Dits when he bought the brewery. As noted in his book about the brewery (Jean-Louis Dits raconte la bière et la Brasserie à Vapeur, there is also an English version), Dits is determined to keep the contents of the little black book to himself, including all ‘brewer’s secrets’.[1]

The mysterious little black book, containing the brewery’s old recipes. But how far do they go back?

Dits’ book does however provide some clues about the little black book. There’s even a picture of it. It looks like it’s from the early twentieth century, with its graph paper. In fact, most information in it seems to be from roughly the period of the First World War up to the 1950s. The only recipe that predates the moment when Gaston Biset took over the brewery, in 1926, is the saison (after that, there were also an English-type ale, a grisette and a stout, among others). Why Dits assumes that the saison was already brewed there in 1785, remains unclear. After all, the black book clearly isn’t nearly that old, and elsewhere in Dits’ book, it is indicated that no operational records from the early days of the brewery have survived.[2]

I can only assume that Dits relates this in good faith, and that the black book somehow describes the saison recipe as something that had ‘always’ been made there. The same goes for the idea that the brewery’s saison was made to quench the farm workers’ thirst in summer. Either it’s in the black book or Dits heard the story somewhere, but as we’ll see in an upcoming article, there is little outside evidence for such a use for saison. In any case 1785 seems remarkably early for a saison in Hainaut. The earliest mention I found for a saison in that region dates from 1858, and from 1823 in the whole of Belgium.[3] Instead, in 19th-century sources about beer in Hainaut, saison is usually remarkably absent.[4]

In any case, I found my two hours’ drive to Brasserie à Vapeur totally worth it. Not only do you get the spectacle of one of the oldest breweries in the world still in operation, but more importantly, you get a very warm welcome from Jean-Louis Dits, Vinciane and their helpers. First-class Belgian hospitality in a tiny Wallonian village. It’s one of the most wonderful Belgian beer experiences you’ll ever get.

Visit: www.vapeur.com

[1] Jean-Louis Dits and Louis-Michel Carpentier, Jean-Louis Dits raconte la bière et la Brasserie à Vapeur, Pipaix 2005, p. 62-63. A kind donation by the author.

[2] Dits and Carpentier, Jean-Louis Dits raconte, p. 44, 62-63, 104.

[3] I will delve into this further in an upcoming article.

[4] Cf. Ph. Vander Maelen, Dictionnaire géographique de la province de Hainaut, Brussels 1823. This book goes at long length to describe all the towns and villages of Hainaut with remarks on the beers brewed there. It doesn’t mention saison at all. 19th century brewing manuals like the ones by Vrancken (1829) and Lacambre (1851) are completely silent on saison being brewed in Hainaut.

Vous ne trouverez jamais de mentions d’une bière “Saison” car elle s’appelait (vieille) Provision. Il n’y avait pas d’étiquette mais un trait de craie sur les bouteilles quand il y en avait. La Provision était la plupart du temps livrée en fût dans la cave du client.