Thanks to the magic lantern: lambic is (slightly) older than we thought

It will happen someday: my book on the history of Belgian beers. Already I’m working on a timeline, not unlike the one featured in my book on lost Dutch beers, published in 2017: an overview of which beer types existed from when, and in many cases, when they disappeared. Therefore, I keep on looking for the earliest (and latest) mentions of certain beers. Since when have we known white beer, grisette, Flemish old brown and saison? That’s why I was happy as a pig in muck last week, when I found a new starting date for one of my favourite beer types: lambic. And it has everything to do with a magic lantern.

It will happen someday: my book on the history of Belgian beers. Already I’m working on a timeline, not unlike the one featured in my book on lost Dutch beers, published in 2017: an overview of which beer types existed from when, and in many cases, when they disappeared. Therefore, I keep on looking for the earliest (and latest) mentions of certain beers. Since when have we known white beer, grisette, Flemish old brown and saison? That’s why I was happy as a pig in muck last week, when I found a new starting date for one of my favourite beer types: lambic. And it has everything to do with a magic lantern.

As beer lovers know, lambic is a beer type from the Brussels region, in Belgium. Still brewed traditionally with spontaneous fermentation. ‘Traditionally’ is not just a buzz word here: many lambic breweries are still housed in old crooked buildings, where not even one little cobweb in the attic is ever changed. Spontaneous fermentation, which means that fermentation starts without the brewer actively adding any yeast, is strongly dependent on the micro-organisms that happen to be in the air in the building’s direct surroundings. Today, lambic aged for a few years in wooden barrels is the base beer from which the varieties gueuze, faro, kriek and various other fruit beers are blended.

But since when has lambic been around? It has been claimed that it is ‘the oldest beer style’, which assumes that during the Middle Ages all beers were spontaneously fermented, but that notion can easily be dismissed. And then there is the ‘recipe’ allegedly written down in 1559 in the city of Halle. A closer study has taught us that it is a description of beers called ‘keute’ and ‘houppe’, which were more of a kind of white beer.

No, lambic isn’t nearly as old as that. In the late 17th century, Brussels knew beers called Dobbel, Bras-pennincx and small beer.[1] In any case, in Western Europe, the trend of ageing beers seems to date from the 18th century. Therefore it is only in 1721, this year exactly 300 years ago, that the first lambic-like beer in Brussels is attested. In those days the Dutch adventurer and multi-talent Jacob Campo Weyerman, born in an army camp near Charleroi, wrote his own little magazine called De Rotterdamse Hermes. In the issue of 14 August 1721 he related the tale of a cabinetmaker in Brussels, who had won the great sum of three thousand golden coins while playing cards. A great host of relatives came to congratulate him, and he treated them to brandy, sweet buns, salted fish and an enormous ‘expenditure of beer from Leuven, Faro, kaves from Lier, Hoegaerts and similar drunkard’s sherbets’[2] At the time, the white beer of Leuven, the caves of Lier and the beer of Hoegaarden all were well-known beer types in what is now Belgium, and from then on faro was apparently also part of the list.

No, lambic isn’t nearly as old as that. In the late 17th century, Brussels knew beers called Dobbel, Bras-pennincx and small beer.[1] In any case, in Western Europe, the trend of ageing beers seems to date from the 18th century. Therefore it is only in 1721, this year exactly 300 years ago, that the first lambic-like beer in Brussels is attested. In those days the Dutch adventurer and multi-talent Jacob Campo Weyerman, born in an army camp near Charleroi, wrote his own little magazine called De Rotterdamse Hermes. In the issue of 14 August 1721 he related the tale of a cabinetmaker in Brussels, who had won the great sum of three thousand golden coins while playing cards. A great host of relatives came to congratulate him, and he treated them to brandy, sweet buns, salted fish and an enormous ‘expenditure of beer from Leuven, Faro, kaves from Lier, Hoegaerts and similar drunkard’s sherbets’[2] At the time, the white beer of Leuven, the caves of Lier and the beer of Hoegaarden all were well-known beer types in what is now Belgium, and from then on faro was apparently also part of the list.

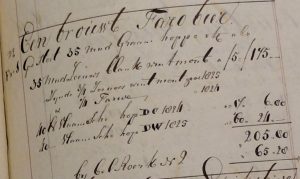

In those days, faro very likely was not sweetened as it is today, and it must have been a beer type of its own, and not a blend from something else. After all, lambic did not exist yet, and as late as the 1820s, in the records of the Scheepje brewery in Haarlem (in Holland, where they brewed faro and lambic as an imitation of the Brussels originals), there are separate brews of faro, next to brews of lambic.[3] As a matter of interest, there already was a beer called pharo or faro in 16th and 17th-century Holland and Zeeland, but we know little on how it was made, and it seems to have been largely extinct there by the time it resurfaced in Brussels.[4]

In those days, faro very likely was not sweetened as it is today, and it must have been a beer type of its own, and not a blend from something else. After all, lambic did not exist yet, and as late as the 1820s, in the records of the Scheepje brewery in Haarlem (in Holland, where they brewed faro and lambic as an imitation of the Brussels originals), there are separate brews of faro, next to brews of lambic.[3] As a matter of interest, there already was a beer called pharo or faro in 16th and 17th-century Holland and Zeeland, but we know little on how it was made, and it seems to have been largely extinct there by the time it resurfaced in Brussels.[4]

After 1721, it would take some time before we hear more on faro from Brussels. In 1775 a brewer in Asse (some 13 km outside Brussels) paid his tithes with three barrels of faro, and in 1783 it was observed that the people of Mons preferred the beers of Mechelen, Leuven, Hoegaarden or ‘the beer of Brussels that is called faro’ to their local brews.[5]

But what about lambic, and where does that name come from? It has been explained as a form of Latin ‘lambere’ (to lick), Spanish ‘el ambiguo’ (‘the ambiguous one’) or the placename Lembeek. However, the sources tell us that during the first decades of its existence, it was known as ‘alambic’ or ‘allambique’. This clearly refers to the French, originally Arabic term ‘alambic’, which means ‘still’, as in ‘kettle used for distilling beverages’. The ‘a’ at the beginning slowly eroded until it was gone.

But what about lambic, and where does that name come from? It has been explained as a form of Latin ‘lambere’ (to lick), Spanish ‘el ambiguo’ (‘the ambiguous one’) or the placename Lembeek. However, the sources tell us that during the first decades of its existence, it was known as ‘alambic’ or ‘allambique’. This clearly refers to the French, originally Arabic term ‘alambic’, which means ‘still’, as in ‘kettle used for distilling beverages’. The ‘a’ at the beginning slowly eroded until it was gone.

Since when has lambic been around then? In 1996, archivist Thierry Delplancq found a document dated 21 November 1794, describing a dispute between an innkeeper and a certain brewer’s widow Van Assche on four barrels of ‘allambique’ worth 32 pounds a barrel.[6]

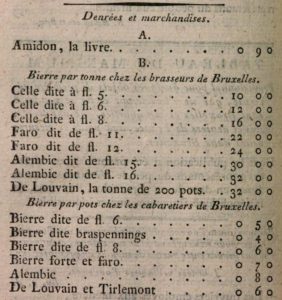

At that moment, the territory that is now Belgium had just been conquered by revolutionary France, and to well-known lambic brewer Frank Boon this is what explained the name (a)lambic: as the French had banned distilling gin at a certain moment, the distillers who secretly continued working, allegedly masked their activities by also making a beer named after their still. A claim easily debunked by critical blogger Raf Meert: the mention of the widow’s four barrels of allambique predates the French distilling ban by over a month. On top of that, Raf provided a slightly older source: on 10 September 1794 the French fixed maximum prices for various foodstuffs in Brussels, among which those of faro (at 22 to 24 pounds) and ‘alembic’ (at 30 to 32 pounds).[7]

At that moment, the territory that is now Belgium had just been conquered by revolutionary France, and to well-known lambic brewer Frank Boon this is what explained the name (a)lambic: as the French had banned distilling gin at a certain moment, the distillers who secretly continued working, allegedly masked their activities by also making a beer named after their still. A claim easily debunked by critical blogger Raf Meert: the mention of the widow’s four barrels of allambique predates the French distilling ban by over a month. On top of that, Raf provided a slightly older source: on 10 September 1794 the French fixed maximum prices for various foodstuffs in Brussels, among which those of faro (at 22 to 24 pounds) and ‘alembic’ (at 30 to 32 pounds).[7]

For some time, 10 September 1794 has been considered the oldest reference to lambic. But now I’ve found another source, which tells us that this beer type is yet another few years older. A source that lifts it from the era of the French Revolution back to the Ancien Régime that came before.

Since 1715, most of the area that is now Belgium was controlled by Austria. The Belgians had to conform themselves to whatever was decided in Vienna by the emperor. In the 1780s, Joseph II, influenced by the Enlightenment, started introducing all sorts of modernisations. The sort of innovations that would not sound so bad to our ears: limiting the influence of the Catholic church, granting more rights to Jews, and introducing a uniform code of law replacing the labyrinth of local bylaws.

Since 1715, most of the area that is now Belgium was controlled by Austria. The Belgians had to conform themselves to whatever was decided in Vienna by the emperor. In the 1780s, Joseph II, influenced by the Enlightenment, started introducing all sorts of modernisations. The sort of innovations that would not sound so bad to our ears: limiting the influence of the Catholic church, granting more rights to Jews, and introducing a uniform code of law replacing the labyrinth of local bylaws.

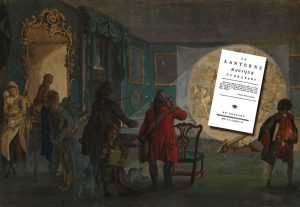

Yet, in the so-called Austrian Netherlands people were not eager to adopt all these novelties and in any case they wanted to finally have their own say on their fate. It was in this context that in 1787 a pamphlet was printed titled La lanterne magique du Brabant, which means ‘The magic lantern of Brabant’.[8]

A magic lantern was an optical instrument, similar to a slideshow projector (or nowadays: a video projector), projecting images on the wall. Throughout the 18th century, it was a popular form of entertainment, used in performances by travelling artists, often in the homes of the wealthy. At the same time, the 18th century was the age of the pamphlet: thin booklets, addressing various political themes, often with humoristic texts. In a way, they were the satirical news websites of their time. For a while, various pamphlets were published that supposedly described a magic lantern performance, as a vehicle for a political message. Not unlike a Youtube parody of a well-known tv programme. La lanterne magique du Brabant was one of the first of this type.[9]

A magic lantern was an optical instrument, similar to a slideshow projector (or nowadays: a video projector), projecting images on the wall. Throughout the 18th century, it was a popular form of entertainment, used in performances by travelling artists, often in the homes of the wealthy. At the same time, the 18th century was the age of the pamphlet: thin booklets, addressing various political themes, often with humoristic texts. In a way, they were the satirical news websites of their time. For a while, various pamphlets were published that supposedly described a magic lantern performance, as a vehicle for a political message. Not unlike a Youtube parody of a well-known tv programme. La lanterne magique du Brabant was one of the first of this type.[9]

The actual pamphlet is rather hard to follow for a 21th century reader, lampooning many politicians of the time. It consists of only eight pages, and describes an artist hauling from Savoye, walking through the streets of Brussels, until he is invited into a home to provide a show with the magic lantern. In the first image shown, we supposedly see Brussels lawyer Hendrik van der Noot, who two years later would lead an actual uprising against the emperor. And then, in the third image, we see a Brussels street, where bonfires have been lit. Candles and Chinese lanterns everywhere, and as a sign of joy there are fountains of ‘le faro, l’alembic, le punch’![10]

So there it is. Lambic turns out to be another seven years older than we thought. Interestingly, this aligns with a text from 1829, in which Leuven-based doctor of medicine Jean-Baptiste Vrancken mentions a 42-year old lambic. A short calculation tells us that it would date from 1787 as well. Vrancken tells us four people drank of this old lambic, who all quickly got plastered.[11]

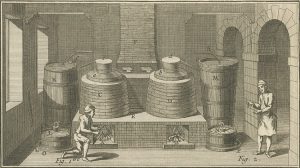

Unfortunately, little is known of this ‘primordial’ lambic and faro. In 1799 however, Jacobus Buys, a brewer from Klundert in the Netherlands, did already describe the spontaneous fermentation and the long keeping times of the beers of Brussels: ‘In Brussels, the brewers do not draw any yeast from their brown beer, that they deliver to customers that keep it for the entire summer, and it tastes and ages, once it has become old and mature, very well.’[12]

Another early description where we recognise the typical properties of faro and lambic can be found in a French medical dictionary from 1812: ‘The rich beers of Brussels are headier and less nutritive, and can be sent over considerable distances: the faro, by its smell and taste very punchy and alcoholic, somewhat approaches certain old ciders and perries, and it has, like these drinks, stimulating and even somewhat irritating qualities; the alambic is even stronger and headier, especially when it has been aged: both could be used to treat adynamic fevers, instead of wine. The best double beers of Paris, Amiens etc. are much weaker and could not be used with the same amount of success.’[13]

Another early description where we recognise the typical properties of faro and lambic can be found in a French medical dictionary from 1812: ‘The rich beers of Brussels are headier and less nutritive, and can be sent over considerable distances: the faro, by its smell and taste very punchy and alcoholic, somewhat approaches certain old ciders and perries, and it has, like these drinks, stimulating and even somewhat irritating qualities; the alambic is even stronger and headier, especially when it has been aged: both could be used to treat adynamic fevers, instead of wine. The best double beers of Paris, Amiens etc. are much weaker and could not be used with the same amount of success.’[13]

All in all, there remains a lot of research to be done on the history of lambic. But as you can see, new sources keep surfacing, new pieces that can make the puzzle a little bit more complete each time. It will only make the delicious gueuze, today still produced as of old, taste even better.

[1] Ordonnantie op het stuck van brouwen, Brussels 1698.

[2] Jacob Campo Weyerman, De Rotterdamsche Hermes, Amsterdam 1980, p. 391.

[3] Archives of North Holland, Archive ’t Scheepje brewery in Haarlem , inv. no. 198.

[4] Marco Daane, Bier in Nederland. Een biografie, Amsterdam 2016, p. 76-80.

[5] Thierry Delplancq, ‘Les brasseurs de lambic. Données historiques et géographiques (XVIIIe S. – XXe S.) (1)’, in: Archives et bibliothèques de Belgique, volume 67 (1996), nr. 1-4, p. 257-320, here p. 261; Le voyageur dans les Pays-Bas autrichiens, ou Lettres sur l’état actuel de ces pays, volume 6 part 1, Amsterdam 1783, p. 193.

[6] Delplancq, ‘Les brasseurs de lambic’, p. 260.

[7] https://lambik1801.wordpress.com/2015/10/22/eerste-lambik-komt-niet-uit-lembeek/ (today offline, can be consulted in the Wayback Machine); Recueil des proclamations et arrêtés des représentans du peuple français , envoyés près des armées du Nord et de Sambre et Meuse, Tome I Cahier I, Brussels 1794, p. 138.

[8] La lanterne magique du Brabant, s.l. 1787.

[9] Jean-Jacques Tatin-Gourier, ‘La lanterne magique: pluralité des imaginaires et des formes d’ecriture’, in: Jean-Jacques Tatin-Gourier (red.), La lanterne magique, pratiques et mise en écriture, Tours 1997, p. 5-16.

[10] La lanterne magique du Brabant, s.l. 1787, p. 5.

[11] Jean Baptiste Vrancken, ‘Antwoord op vraag 81’, in: Nieuwe verhandelingen van het Bataafsch Genootschap der Proefondervindelijke Wijsbegeerte te Rotterdam, Rotterdam 1829, p. 132.

[12] Jakobus Buys, De bierbrouwer of volledige beschrijving van het brouwen der bieren, Dordrecht 1799, p. 39. Strictly speaking, Buys is talking of not withdrawing yeast, which then can not be used for the next brew. The preceding sentence however clearly speaks of adding yeast in the conventional brewing method, with which the Brussels practice is constrasted.

[13] Adelon et al., Dictionaire des sciences médicales, par une société de médecins et de chirurgiens, Paris 1812, p. 119.

Love what you are doing. Thx!

Lovely story and very thoughtful comment on some rare and interesting scholarship. Enjoyed it immensely. Wonderful to find your website and blog. Please continue to share your finds and thoughts! Cheers!

Very nice research. Update me please