Stella Artois: so is it a Christmas beer or not?

We need to talk about Stella Artois. This pilsener-type lager is the flagship beer of AB InBev, the world’s biggest brewery. A beer of which the makers want it to ooze quality, which is why in English-speaking countries it was often advertised as ‘reassuringly expensive’. In Belgium itself, it has already lost its splendour long ago. Anyway, because every beer needs a marketing story (and because lager has become such a bland product), for Stella they will often tell you that it originally was a Christmas beer, when it was introduced in 1926. But was it?

We need to talk about Stella Artois. This pilsener-type lager is the flagship beer of AB InBev, the world’s biggest brewery. A beer of which the makers want it to ooze quality, which is why in English-speaking countries it was often advertised as ‘reassuringly expensive’. In Belgium itself, it has already lost its splendour long ago. Anyway, because every beer needs a marketing story (and because lager has become such a bland product), for Stella they will often tell you that it originally was a Christmas beer, when it was introduced in 1926. But was it?

For centuries the Artois brewery in Leuven made only the local white beer and an amber-coloured variant called peeterman, top-fermented multi-grain beers that were shipped to various other regions in Belgium. However, in 1892 a new brewhouse was added to make bottom-fermented German-style beers. Artois bought a German brewing installation, hired German and Czech brewers and bought German raw materials.[1] They were following a relatively new trend in Belgium, where the first serious bottom-fermenting breweries only were created after a new beer law was passed in 1885. The most popular beers were the light-coloured Bock, the dark Munich and the lighter petite Bavière.[2]

For centuries the Artois brewery in Leuven made only the local white beer and an amber-coloured variant called peeterman, top-fermented multi-grain beers that were shipped to various other regions in Belgium. However, in 1892 a new brewhouse was added to make bottom-fermented German-style beers. Artois bought a German brewing installation, hired German and Czech brewers and bought German raw materials.[1] They were following a relatively new trend in Belgium, where the first serious bottom-fermenting breweries only were created after a new beer law was passed in 1885. The most popular beers were the light-coloured Bock, the dark Munich and the lighter petite Bavière.[2]

This German beer enabled a further expansion at Artois: between 1901 and 1914 production doubled. The old white beer lagged behind: the share of bottom-fermented beers in total sales went from 44% to 58%. All in all, Artois quickly rose to the position of second-largest brewery in Belgium.[3]

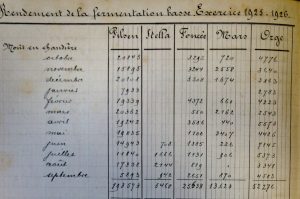

I travelled to Leuven, where in the National Archives I was allowed to snoop around in the dusty Artois files.[4] Dusty they were: after an afternoon of browsing, my fingers were black! But somewhere in those yellowed pages I actually found the birth certificate of Stella Artois. In June 1926 it was first mentioned as a beer being brewed. This was not done on a whim: the year before, Artois had already been experimenting with a new beer, then simply called ‘X’ in the brewing logs. It was a blonde beer, a bit stronger than the other beers produced up to that point. The malt was, in their own words, of best Czech quality, and the only hops used were Saaz. After a while, fermentation took place at the unusually high temperature of 11.5º C.[5]

I travelled to Leuven, where in the National Archives I was allowed to snoop around in the dusty Artois files.[4] Dusty they were: after an afternoon of browsing, my fingers were black! But somewhere in those yellowed pages I actually found the birth certificate of Stella Artois. In June 1926 it was first mentioned as a beer being brewed. This was not done on a whim: the year before, Artois had already been experimenting with a new beer, then simply called ‘X’ in the brewing logs. It was a blonde beer, a bit stronger than the other beers produced up to that point. The malt was, in their own words, of best Czech quality, and the only hops used were Saaz. After a while, fermentation took place at the unusually high temperature of 11.5º C.[5]

Does this mean that Stella marks the beginning of the production of pilsener at Artois? Oddly, it doesn’t. The beer they sold as ‘Bock’ had been indicated as ‘Pilsen’ in the brewing books since 1910.[6] This means that when in 1926 they started making Stella, there already was a pilsener in the records, but it was a different beer altogether! Even more so, for years Stella wasn’t called a pilsener, it was considered a beer type by itself, just like the beers Salva (a kind of Munich) and Sparta that were introduced later on. Meanwhile, by October 1932 they dropped the in-house name ‘Pilsen’ for their Bock. It seems that only by the 1970s Artois adapted the label ‘pils’ for their Stella.[7]

Does this mean that Stella marks the beginning of the production of pilsener at Artois? Oddly, it doesn’t. The beer they sold as ‘Bock’ had been indicated as ‘Pilsen’ in the brewing books since 1910.[6] This means that when in 1926 they started making Stella, there already was a pilsener in the records, but it was a different beer altogether! Even more so, for years Stella wasn’t called a pilsener, it was considered a beer type by itself, just like the beers Salva (a kind of Munich) and Sparta that were introduced later on. Meanwhile, by October 1932 they dropped the in-house name ‘Pilsen’ for their Bock. It seems that only by the 1970s Artois adapted the label ‘pils’ for their Stella.[7]

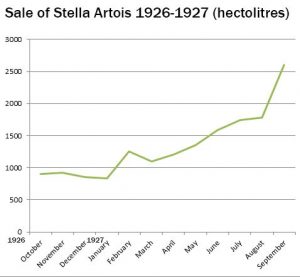

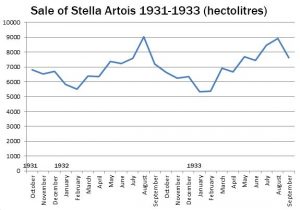

Second question: was Stella a Christmas beer? The name seems to suggest this (‘Stella’ means ‘star’ in Latin), but the original records tell a different story. It was first brewed in June (cf. this advert which suggests it was during the winter), and after a few months of lagering it was put on the market in September 1926. After that, the monthly sales paint an interesting picture. Sales remained at more or less the same level until November, and dropped slightly in December 1926 and January 1927! In 1927 sales just rose again, especially during summer. Sure, it can happen that a Christmas beer is already sold to retailers in November, but even if in 1926 it may have been intended as a holiday beer, they were quick to drop this seasonality. During the accounting years of 1931-1933, Stella Artois sales clearly peaked during summer. By that time it made up 16% of total production. Almost half was still Bock.

Second question: was Stella a Christmas beer? The name seems to suggest this (‘Stella’ means ‘star’ in Latin), but the original records tell a different story. It was first brewed in June (cf. this advert which suggests it was during the winter), and after a few months of lagering it was put on the market in September 1926. After that, the monthly sales paint an interesting picture. Sales remained at more or less the same level until November, and dropped slightly in December 1926 and January 1927! In 1927 sales just rose again, especially during summer. Sure, it can happen that a Christmas beer is already sold to retailers in November, but even if in 1926 it may have been intended as a holiday beer, they were quick to drop this seasonality. During the accounting years of 1931-1933, Stella Artois sales clearly peaked during summer. By that time it made up 16% of total production. Almost half was still Bock.

At Artois they clearly intended to simply keep selling Stella all year. So where does the Christmas story come from? I have seen nothing from 1926 to suggest a Christmas theme for Stella Artois, which of course doesn’t mean that this never may have been the original intention. However, in Belgium pilsener certainly wasn’t considered a typical beer for Christmas, that honour was reserved for dark Scotch ale (more on that soon…). (Edit: to be fair, Haacht brewery has made a ‘Super Christmas pils‘ at some point.)

At Artois they clearly intended to simply keep selling Stella all year. So where does the Christmas story come from? I have seen nothing from 1926 to suggest a Christmas theme for Stella Artois, which of course doesn’t mean that this never may have been the original intention. However, in Belgium pilsener certainly wasn’t considered a typical beer for Christmas, that honour was reserved for dark Scotch ale (more on that soon…). (Edit: to be fair, Haacht brewery has made a ‘Super Christmas pils‘ at some point.)

What does strike me about the phenomenon of pilsener in Belgium in those days, is that it wasn’t really a thing. Almost no-one actually made it. I did find earlier examples of Belgian breweries that next to Bock and Munich advertised their ‘Pilsen’, but it met with very little success.[8] There was even some mushrooming of weird variants like ‘double pilsen’, ‘triple-pils’ and ‘pilsen de table’.[9]  The beer that currently is marketed as being Belgium’s first pils is Cristal, introduced in 1928 by the Alken brewery from the village with the same name in Belgian Limburg. But when you look up old labels of it, you find that also there the word ‘Pilsen’ or ‘Pilsener’ seems to have been carefully avoided. As a side note, there were warm ties between Artois and Alken: Léon Verhelst, president of Artois and professor at Leuven brewing school, served as an advisor to the founders of Alken, and from 1932 to 1947 Artois actually had some shares in the company.[10]

The beer that currently is marketed as being Belgium’s first pils is Cristal, introduced in 1928 by the Alken brewery from the village with the same name in Belgian Limburg. But when you look up old labels of it, you find that also there the word ‘Pilsen’ or ‘Pilsener’ seems to have been carefully avoided. As a side note, there were warm ties between Artois and Alken: Léon Verhelst, president of Artois and professor at Leuven brewing school, served as an advisor to the founders of Alken, and from 1932 to 1947 Artois actually had some shares in the company.[10]

At Artois, Stella slowly came to dominate all the other beers. Just before the Second World War, it made up 24% of production, against 50% of Bock and only a modest 9% of old-fashioned top-fermented beer.[11] During the war, the brewery was heavily damaged, especially during bombings in 1944. Most of the complex needed to be rebuilt. After the war, Stella definitely rose to the status of the company’s figurehead. Folders and brochures from the 1960s and 1970s hardly show any other beers. At the same time, Artois came to dominate the Belgian market: already in the 1930s they had started to take over other breweries. Also, they seriously started exporting and expanding abroad. In Belgium itself, one brewery after the other fell down and came under the spell of Artois, which spread throughout the country.

At Artois, Stella slowly came to dominate all the other beers. Just before the Second World War, it made up 24% of production, against 50% of Bock and only a modest 9% of old-fashioned top-fermented beer.[11] During the war, the brewery was heavily damaged, especially during bombings in 1944. Most of the complex needed to be rebuilt. After the war, Stella definitely rose to the status of the company’s figurehead. Folders and brochures from the 1960s and 1970s hardly show any other beers. At the same time, Artois came to dominate the Belgian market: already in the 1930s they had started to take over other breweries. Also, they seriously started exporting and expanding abroad. In Belgium itself, one brewery after the other fell down and came under the spell of Artois, which spread throughout the country.

So why is it not Stella Artois, but Jupiler whose name seems to be on every pub sign in the country? That’s because the people at Piedboeuf in Jupille near Liège were such clever businessmen. In 1971, Artois and Piedboeuf had made a secret gentlemen’s agreement to cooperate in the Belgian market. At that time, Stella was still by far Belgium’s most important pilsener. However Piedboeuf was smaller but on the rise, and with its Jupiler it cleverly ate away Stella’s market share in Belgium, not in the least because there was a rumour (spread by Piedboeuf?) that Stella was a ‘headache beer’. In any case, despite the agreement Jupiler was Stella’s biggest competitor![12] By 1988, when the actual merger took place (the result, Interbrew, was then no. 18 worldwide), throughout Belgium pubs were covered in Jupiler signs.

So why is it not Stella Artois, but Jupiler whose name seems to be on every pub sign in the country? That’s because the people at Piedboeuf in Jupille near Liège were such clever businessmen. In 1971, Artois and Piedboeuf had made a secret gentlemen’s agreement to cooperate in the Belgian market. At that time, Stella was still by far Belgium’s most important pilsener. However Piedboeuf was smaller but on the rise, and with its Jupiler it cleverly ate away Stella’s market share in Belgium, not in the least because there was a rumour (spread by Piedboeuf?) that Stella was a ‘headache beer’. In any case, despite the agreement Jupiler was Stella’s biggest competitor![12] By 1988, when the actual merger took place (the result, Interbrew, was then no. 18 worldwide), throughout Belgium pubs were covered in Jupiler signs.

In Belgium, Stella Artois nowadays is a typical petrol station beer, only in Leuven itself it still is a popular brand. But even there they have to watch out: in 2016 InBev, obsessed with marketing like many other big breweries, started replacing the traditional ribbed beer glasses from which students and workmen drink their tipple, with the chic but pretentious chalice glass it uses abroad. It caused a storm of protest.[13] All that for this wretched ‘Premium’ appearance that they seem to find important. (My personal view: it will take only a couple of years before the word ‘Premium’ will have lost all of its meaning anyway.) They will have to be careful not to make this explode in their face, alienating the drinkers from them even further…

The Artois brewery and its roots

Stella was conceived by the Artois brewery in Leuven. Since 1717, the Artois family owned the brewery (Den Hoorn, a brewery that had been around since 1466, still a century later than the erroneous year 1366 shown on the labels).[14] In 1840 the Artois family died out, and through inheritances it came into the hands of the noble de Mevius and de Spoelberch families.[15] Already by the end of the 18th century the brewery’s owners were quite well off, but during the 20th century the company, after merging with Piedboeuf near Liège, emerged as the biggest brewery in the world. Its owners are now by far the richest people in Belgium.[16]

Stella was conceived by the Artois brewery in Leuven. Since 1717, the Artois family owned the brewery (Den Hoorn, a brewery that had been around since 1466, still a century later than the erroneous year 1366 shown on the labels).[14] In 1840 the Artois family died out, and through inheritances it came into the hands of the noble de Mevius and de Spoelberch families.[15] Already by the end of the 18th century the brewery’s owners were quite well off, but during the 20th century the company, after merging with Piedboeuf near Liège, emerged as the biggest brewery in the world. Its owners are now by far the richest people in Belgium.[16]

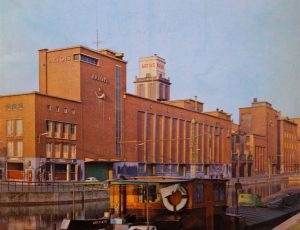

If you go to Leuven to see the place where Den Hoorn brewery was situated, in the Mechelsestraat, you will find nothing more than a gaping hole with a messy wasteland behind it. This is because by the end of the 18th century, the company’s focus shifted to buildings at the Vaartkom, the basin where the canal to Mechelen starts. The old Den Hoorn brewery was turned into a malthouse and later demolished. By now, at the Vaartkom things are just as messy: the actual brewery has relocated even more to the East, and for years the buildings from the 1920s and 1950s slowly deteriorated. Now they will be demolished, and partially repurposed in a large-scale city renewal program.

[1] http://www.beerculture.org/2016/05/12/a-czech-influence-on-belgian-brewing/

[2] Paul Godaert, Les présidents des brasseries Artois: Léon Verhelst, Henry van den Schrieck, Werner de Spoelbergh, Raymond Boon, Virton 1993, p. 23.

[3] Godaert, Les présidents des brasseries Artois, p. 43, 54.

[4] National Archives Leuven, archives Artois breweries. With special thanks to the archivist Mr. Carnier.

[5] Godaert, Les présidents des brasseries Artois, p. 83.

[6] Only for a short while it must have been sold as ‘Bock-Pilsen’, as shown by labels on jacquestrifin.be. A 1931 price list calls it ‘Bock’, while the brewing logs still called it ‘Pilsen’. It wasn’t until October 1932 that the internal documents call it ‘Bock’ again.

[7] Steven Wilsens, Leuven hoofdstad van het bier, Leuven 1976. In it, a brochure describes Stella Artois as ‘The first-rate Pils’.

[8] In 1909 Bavaro-Belge in Antwerpen already advertised its pilsen, Caulier in Brussels did so in 1920, and Van den Heuvel in Brussels in 1924. De Vlaamsche wacht 26-9-1909; De Poperinghenaar 25-7-1920; De Gazet van Poperinghe 16-3-1924.

[9] Cf. labels by Burny in Aalst, L’Abbaye St. Arnould in Jemappes and Labor in Mons at jacquestrifin.be.

[10] Godaert, Les présidents des brasseries Artois, p. 93-94. There is some confusion about the actual year Cristal Alken was born: the brewery itself says it’s 1928, brewer Indekeu claims it was 1927 and the actual production is said to have started in August 1929. Ivan Derycke (red.), Antwerpen bierstad. Acht eeuwen biercultuur, Brasschaat 2011, p. 84 note 297.

[11] Godaert, Les présidents des brasseries Artois, p. 91.

[12] Wolfgang Riepl, De Belgische bierbaronnen. Het verhaal achter Anheuser-Busch InBev, Roeselare 2009.

[13] https://www.hln.be/regio/leuven/stella-stopt-met-ribbelkes~ac1d841f; https://www.demorgen.be/binnenland/leuven-lust-chique-stijl-stella-artois-niet-b80658d7.

[14] Tom Avermaete, ‘De oorsprong van de Leuvense brouwerij Den Horen’, in: Oost-Brabant jaargang 41 (2004) nr. 4, p. 182-187.

[15] Paul Godaert, Les Artois et leurs successeurs Albert Marnef, Edmond Willems, Virton 1994.

[16] derijkstebelgen.be

Leave a Reply