Georges Lacambre: the man who taught Belgium how to brew

On May 30, 1884 a man was buried at the Cimétière de Passy in Paris, in a grave on section 1, row 8 south, number 3 east.[1] This graveyard, today located within a short walking distance from the Eiffel tower, looks just like you’d imagine a cemetary in Paris: lots of robust small tombs the size of telephone boxes, statues of mourning angels, and shiploads of expensive looking marble. This is where he found his last resting place: Georges Lacambre, the man who taught Belgium how to brew.

On May 30, 1884 a man was buried at the Cimétière de Passy in Paris, in a grave on section 1, row 8 south, number 3 east.[1] This graveyard, today located within a short walking distance from the Eiffel tower, looks just like you’d imagine a cemetary in Paris: lots of robust small tombs the size of telephone boxes, statues of mourning angels, and shiploads of expensive looking marble. This is where he found his last resting place: Georges Lacambre, the man who taught Belgium how to brew.

Of course, it’s nonsense. Belgians had been brewing for centuries. But Lacambre was the first to give a comprehensive account of the brewing methods and techniques used in Belgium, in his 1851 book Traité complet de la fabrication de bières et de la distillation des grains.[2] For over half a century, it would be the go-to brewing manual that many a Belgian and northern French brewer would always have within reach.

In over five hundred pages Lacambre described the raw materials, the malting process, brewing and fermentation, using the latest scientific knowledge available. He extensively commented on modern brewing methods used in England and Germany, and the real gem for us beer history geeks is his survey of the various beers made in Belgium itself, including many that have vanished since, such as the peeterman of Leuven, the caves of Lier, the uitzet of Flanders and the barley beer of Antwerp. If we know today how lambic was made at the time, or Hoegaarden‘s white beer, it’s because of Lacambre’s book.

In over five hundred pages Lacambre described the raw materials, the malting process, brewing and fermentation, using the latest scientific knowledge available. He extensively commented on modern brewing methods used in England and Germany, and the real gem for us beer history geeks is his survey of the various beers made in Belgium itself, including many that have vanished since, such as the peeterman of Leuven, the caves of Lier, the uitzet of Flanders and the barley beer of Antwerp. If we know today how lambic was made at the time, or Hoegaarden‘s white beer, it’s because of Lacambre’s book.

Anyone who writes anything on Belgian beer history, cannot ignore Lacambre (although it helps if you can read French).[3] Therefore it is all the more remarkable that no-one actually bothered to find out who he really was. I guess the task once again falls to me. For a start, he was not from Belgium.

Germain Pierre Georges Lacambre was born on May 28, 1811 in the hamlet of La Poujade, in the community of Altillac, in the Limousin region in central France. There, his father was a lawyer and a justice of the peace. The Limousin is not exactly a beer brewing area. It’s more of a wine region, if anything. Unfortunately, Lacambre did not write down an awful lot about himself, which means we have to reconstruct his life with the jigsaw pieces that we have available. In 1835 he graduated from the prestigious Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in Paris. This institute was founded in 1829 with the goal of combining science and technology, by training people as civil engineers. Alumni were expected to be generalists, deployable anywhere.

Germain Pierre Georges Lacambre was born on May 28, 1811 in the hamlet of La Poujade, in the community of Altillac, in the Limousin region in central France. There, his father was a lawyer and a justice of the peace. The Limousin is not exactly a beer brewing area. It’s more of a wine region, if anything. Unfortunately, Lacambre did not write down an awful lot about himself, which means we have to reconstruct his life with the jigsaw pieces that we have available. In 1835 he graduated from the prestigious Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in Paris. This institute was founded in 1829 with the goal of combining science and technology, by training people as civil engineers. Alumni were expected to be generalists, deployable anywhere.

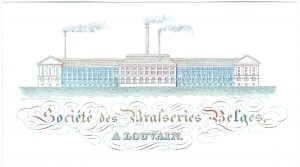

How did Lacambre end up in brewing? It’s impossible to say. In any case, in 1836 he went to Leuven together with his fellow student Charles Ernest Persac (1806-1873) to set up the brewhouse at the Société des Brasseries Belges there.

This company had been founded in 1835 one Renier Hambrouck, who had bought the grounds of the former abbey of Our Lady of the Vineyard in Leuven. For Hambrouck, Lacambre and Persac established a large, modern brewhouse, naturally with a steam engine. The complex was so big that it was locally known as the ‘monster brewery’![4]

This company had been founded in 1835 one Renier Hambrouck, who had bought the grounds of the former abbey of Our Lady of the Vineyard in Leuven. For Hambrouck, Lacambre and Persac established a large, modern brewhouse, naturally with a steam engine. The complex was so big that it was locally known as the ‘monster brewery’![4]

Meanwhile, Lacambre had visited several breweries in England, Belgium and Germany where he had a thourough look around. Once the brewery in Leuven was ready, he became the head brewer there, overseeing the brewing of the typical Leuven white beer but also of English-style ales. There also was a small test brewery where he could experiment to his heart’s content.

Something else was brewing for Lacambre too: in 1840 he married 27 year old Leuven-born Hyacinthe Euphrosine Anchiaux.[5] Such a fine-sounding name would make you suspect she was from a well-to-do family, and so she was: her father was a landowner of independent means. Subsequently, cadastral records show Lacambre and his wife as proprietors of land and houses in rural Brabant communities such as Molenbeek-Wersbeek, Rillaar, Tielt-Onze-Lieve-Vrouw and Kaggevinne.[6]

However, Hyacinthe Anchiaux also had some brewer’s blood running through her veins. Her maternal grandfather was a brewer in Mechelen, and her aunt was Regina Wauters, who was married to Pedro Rodenbach, one of the founders of the brewery with the name same in Roeselare still extant today. Even more so, that same Pedro Rodenbach was one of the witnesses at Lacambre’s wedding, as an uncle of the bride!

However, Hyacinthe Anchiaux also had some brewer’s blood running through her veins. Her maternal grandfather was a brewer in Mechelen, and her aunt was Regina Wauters, who was married to Pedro Rodenbach, one of the founders of the brewery with the name same in Roeselare still extant today. Even more so, that same Pedro Rodenbach was one of the witnesses at Lacambre’s wedding, as an uncle of the bride!

In 1840 Georges Lacambre left the ‘monster brewery’ in Leuven. We don’t know why. What’s more, although he was apparently already busy writing his brewing manual, he started occupying himself with various other matters. That same year he set op a dextrin syrup factury in Heusden for Darbois, Smith & Comp. (a company on which I have not managed to find any other information so far), and later that year together with Persac he applied for patents for a cloth weaving machine, a fan used for airing mines and a way to stop tubes in locomotives from leaking.[7]

During the next few years we see Lacambre, then living in Brussels and subsequently in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode and Schaerbeek, working on heating for public buildings, an oven for glass and crystal and a device for filtering gas used for lighting.[8]

Meanwhile the brewery in Leuven where Lacambre had left was doing less well: financial trouble led to liquidation and forced sale in 1844. In the end, the brewery was relaunched under the name La Vignette, which was simply the French name of the former monastery that once stood there. La Vignette would remain in business until 1937, when it was taken over by Artois.[9] Little remains from the days of Lacambre on the site today, but locals have started a project of reviving the La Vignette brand, of course based on an original Lacambre recipe. To find out more, check out www.lavignettelouvain.be.

In 1851 Georges Lacambre finally published his brewing manual Traité complet, which actually comprised two volumes: the second tome dealt with distilling, on which he apparently was an authority too. In fact, he had planned to issue the book as early as 1848 with a Parisian publisher, but that year’s political unrest made that plan go up in smoke. In any case, the book was apparently recieved positively, as it was reprinted in 1856.

In 1851 Georges Lacambre finally published his brewing manual Traité complet, which actually comprised two volumes: the second tome dealt with distilling, on which he apparently was an authority too. In fact, he had planned to issue the book as early as 1848 with a Parisian publisher, but that year’s political unrest made that plan go up in smoke. In any case, the book was apparently recieved positively, as it was reprinted in 1856.

As a side note, it is striking that it mainly was left to foreigners to publish anything about beer in Belgium in those days. There was for instance a certain Charles Godard (born Caen ca. 1792), originally from Normandy but in the 1830s working in breweries and destilleries in Sint-Jans-Molenbeek and Tienen, among others. He published several books and booklets on brewing.  Unfortunately, he was also a major kook, with idiosyncratic theories on the influence of electrity on malting and many other things. The Paris-based brewer Francois Ferdinand Rohart (Reims 1818 – Paris 1889) wiped the floor with Godard and his crackpot ideas in his 1848 book Traité théorique et pratique de la fabrication de la bière. Rohart’s book was fairly popular in Belgium too, but unfortunately his work does not deal with Belgium specifically.[10]

Unfortunately, he was also a major kook, with idiosyncratic theories on the influence of electrity on malting and many other things. The Paris-based brewer Francois Ferdinand Rohart (Reims 1818 – Paris 1889) wiped the floor with Godard and his crackpot ideas in his 1848 book Traité théorique et pratique de la fabrication de la bière. Rohart’s book was fairly popular in Belgium too, but unfortunately his work does not deal with Belgium specifically.[10]

Someone who did write a lot on the Belgian brewing industry was Frenchman Auguste Laurent (Fresnes-sur-Escaut 1819 – Saint-Laurent-Blagny 1903). In 1859 he founded the brewing journal Moniteur de la brasserie in Brussels, and in 1870 he started issueing a series of highly informative (but unfortunately very rare) booklets called Bibliothèque de la brasserie, of which about thirty volumes were published. Incidentally, his brother Isidore Laurent ran a malthouse near Arras, where he produced a colourant called Brutolicolor, made of cichory, which was heavily advertised in the Moniteur.[11]

With the rise of brewing schools in Belgium in the late 19th century, the Belgians themselves started to take an interest in the theory behind brewing, but it was Englishman George Maw Johnson (Sutton (Suffolk) 1864 – Brussels 1928) who in 1893 started the popular brewer’s magazine Le petit journal du brasseur. Ten years earlier, he had come from Canterbury to Belgium for the first time, where he advised scores of breweries on producing English-style beers. In 1887 he published his book Traité pratique de la brasserie et du maltage anglais et fabrication des bières anglaises. In 1919, his brewer’s journal became the official publication medium of one of the Belgian brewers’ associations, but that’s another story. In the end, after more than a hundred years, the weekly magazine was replaced by a trimestrial periodical called Het brouwersblad.[12]

With the rise of brewing schools in Belgium in the late 19th century, the Belgians themselves started to take an interest in the theory behind brewing, but it was Englishman George Maw Johnson (Sutton (Suffolk) 1864 – Brussels 1928) who in 1893 started the popular brewer’s magazine Le petit journal du brasseur. Ten years earlier, he had come from Canterbury to Belgium for the first time, where he advised scores of breweries on producing English-style beers. In 1887 he published his book Traité pratique de la brasserie et du maltage anglais et fabrication des bières anglaises. In 1919, his brewer’s journal became the official publication medium of one of the Belgian brewers’ associations, but that’s another story. In the end, after more than a hundred years, the weekly magazine was replaced by a trimestrial periodical called Het brouwersblad.[12]

Back to Georges Lacambre. After publishing his brewing manual he filed a few more patents, on subjects like distilling from grains and sugar beet, and the production of glass and mirrors.[13] After that, mostly silence. Did he retire? In 1864, a large amount of books from Lacambre’s collection was put on auction in Brussels.[14] Until 1866, we see him living on Boulevard d’Anderlecht in Brussels, after which he vanishes, only to pop up again in 1874 on Rue Dumont-d’Urville in Paris.[15] What he was doing there, in that posh street filled with large townhouses? Who knows. Maybe he didn’t do much at all, just sitting on his money. Did he still drink a Belgian beer once in a while? Who’s to say. Georges Lacambre died April 4, 1884, at four o’ clock in the night, 72 years old. His wife died a year later.

Back to Georges Lacambre. After publishing his brewing manual he filed a few more patents, on subjects like distilling from grains and sugar beet, and the production of glass and mirrors.[13] After that, mostly silence. Did he retire? In 1864, a large amount of books from Lacambre’s collection was put on auction in Brussels.[14] Until 1866, we see him living on Boulevard d’Anderlecht in Brussels, after which he vanishes, only to pop up again in 1874 on Rue Dumont-d’Urville in Paris.[15] What he was doing there, in that posh street filled with large townhouses? Who knows. Maybe he didn’t do much at all, just sitting on his money. Did he still drink a Belgian beer once in a while? Who’s to say. Georges Lacambre died April 4, 1884, at four o’ clock in the night, 72 years old. His wife died a year later.

They had no children. No portrait of Lacambre has been preserved. The main thing he left behind, is what was cherished by generations of Belgian brewers: his book.

[1] Book of burials (Répertoires annuels d’inhumation) Cimétière de Passy, Archives de Paris.

[2] Georges Lacambre, Traité complet de la fabrication de bières et de la distillation des grains, pommes de terre, vins, betteraves, mélasses, etc., Brussels 1851.

[3] This is of course not the place to discuss the linguistic history of Belgium, but in a nutshell: although in 19th-century Belgium over a half of the population spoke Dutch (‘Flemish’), French was the language of the elite, of politics, of science but also of commerce and industry. Many Dutch-speaking brewers had a reasonable or good knowledge of French. It wasn’t until 1916 that the first serious Belgian brewing manual in Dutch was published, by Hendrik Verlinden.

[4] Rik Uytterhoeven, Leuven, bierstad door de eeuwen heen, Leuven 1983, photos 32-36.

[5] Civil registry of mariages, 24-9-1840 in Leuven.

[6] To be consulted at https://belgica.kbr.be/belgica/popp.aspx?_lg=nl-BE.

[7] L’indépendance belge 22-12-1840, 28-12-1840; Bulletin officiel des lois et arrêtés royaux de la Belgique, volume XXI, (1840), p. 543.

[8] L’indépendance belge 21-5-1841, 30-12-1845; G. Lacambre, Rapport sur les divers systèmes de chauffage et de ventilation adoptés pour les différents édifices et établissements d’utilité publique, Brussels 1845.

[9] Uytterhoeven, Leuven, bierstad door de eeuwen heen.

[10] Cf. Charles Godard, L’art de brasser, Parijs 1842. Charles Goddard (sic), distiller, maried Marie Therese Bulens 20-5-1837 in Sint-Jans-Molenbeek. F. Rohart, Traité théorique et pratique de la fabrication de la bière, volume II, Paris 1848, p. 579-586.

[11] Cf. Auguste Laurent, La bière de l’avenir, Brussel 1873; Almanach des Brasseurs année 1864, Brussels / Paris 1864.

[12] Leidsch dagblad 22-2-1994; Jef Van den Steen, Speciale Belge Ale. Traditiebier van hier, Tielt 2016, p. 12-13; Anne Perrier-Robert en Charles Fontaine, België door het bier. Het bier door België, Esch-sur-Alzette 1996, p. 190. Het brouwersblad was discontinued in 2006, cf. De Standaard 14-6-2007.

[13] L’indépendance belge 16-11-1853; Bulletin des lois de l’Empire français, series XI (1855), p. 1044, 1194.

[14] Catalogue d’une très belle collection de livres anciens et modernes provenant de M. Lacambre (…), Brussels 1864.

[15] Annuaire-almanach du commerce, de l’industrie, de la magistrature et de l’administration, Paris 1874, p. 359.

Strangely enough, over recent years, Limousin has arguably become one of the hubs for brewing in France. I wonder if that is just a coincidence?

Do translations of Lacambre’s work exist in languages other than French? I’m fluent in Dutch and English and could reasonably get by reading a German translation.

I’m only good enough at French, Italian, or Spanish to do anything other than talk my way into trouble, and certainly not good enough to talk my way out of it.