East-Indian Haantjesbier

Last week’s Friday I had the honour of introducing the rebirth of a lost beer: Haantjesbier. At a festival about 19th century rebellious Dutch writers, in Amsterdam, because they were among its original drinkers. And it turned out to be a really good beer!

Last week’s Friday I had the honour of introducing the rebirth of a lost beer: Haantjesbier. At a festival about 19th century rebellious Dutch writers, in Amsterdam, because they were among its original drinkers. And it turned out to be a really good beer!

Last year’s December I received an e-mail from Stephen Grigg of the Utrecht-based Kromme Haring (‘Crooked Herring’) brewery. He was looking for the recipe of Haantjesbier. What happened to be the case? This brewpub started in 2016 thanks to crowdfunding, and the person who had invested the most was invited to choose a beer that he wanted to be brewed. This biggest crowdfunder turned out to be Simon Mulder (no relation): poet, performance artist and organiser of poetry festivals. Always impeccably dressed in costumes that seem to come directly from the 19th century. He wanted to taste the beer that the Tachtigers (from ‘Tachtig’ which means ‘Eighties’) drank at their meetings in the 1880s: Haantjesbier.

The Tachtigers, as many Dutch people vaguely remember from Dutch class in high school, were a group of young, rebellious writers and artists who wanted to resist the complacency of the Dutch bourgeoisie of that time. And Haantjesbier is what was served at the Karseboom café in the Kalverstraat in Amsterdam, where the Tachtigers met in 1881.[1] In fact drinking Haantjesbier was an act of resistance in itself, because the actual fashion of the day in the Netherlands was Bavarian beer, of which the most well-known today is pilsener. It’s no coincidence that Heineken had started brewing its pilsener just the year before, in 1880.[2] The streets of Amsterdam were full of Munich-style beer halls with Bavarian serving girls, who could carry 14 half-litre beer steins at a time.[3] And the Tachtigers were drinking Haantjesbier!

The Tachtigers, as many Dutch people vaguely remember from Dutch class in high school, were a group of young, rebellious writers and artists who wanted to resist the complacency of the Dutch bourgeoisie of that time. And Haantjesbier is what was served at the Karseboom café in the Kalverstraat in Amsterdam, where the Tachtigers met in 1881.[1] In fact drinking Haantjesbier was an act of resistance in itself, because the actual fashion of the day in the Netherlands was Bavarian beer, of which the most well-known today is pilsener. It’s no coincidence that Heineken had started brewing its pilsener just the year before, in 1880.[2] The streets of Amsterdam were full of Munich-style beer halls with Bavarian serving girls, who could carry 14 half-litre beer steins at a time.[3] And the Tachtigers were drinking Haantjesbier!

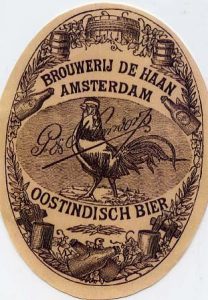

So, what sort of beer was that? Luckily, I was able to enlighten Kromme Haring’s Stephen Grigg and the sympathetic poet Simon Mulder: it originally was a beer meant for the East Indies. It was named after De Haan (‘The cock’ or ‘The rooster’) an Amsterdam brewery on Geldersekade, which was founded in 1611. They specialised in providing the Dutch East India Company. In the Far East, the beer even had medical applications: in the late 17th century, there was already a physician working in the tropics who wrote about a patient at the Coromandel coast in India, who drank Haantjesbier with some nutmeg grated into it. And in 1742 a manual for ship’s surgeons reported that rye flour boiled in Haantjesbier helped to ‘open the stomach’ (that is, it had a laxative effect).[4]

Especially during the 19th century Haantjesbier was widely known in the Dutch Indies. In Malay language, it was called ‘Bier Ajam’: chicken beer.[5] Around 1850, De Haan (by that time called Haan & Sleutels) was one of the two biggest breweries of Amsterdam and the Netherlands as a whole. By 1868 however, they were facing competition from the quickly growing new industrial breweries that made Bavarian beer, like Amstel and Heineken. De Haan & Sleutels had to keep up with its time, and had a second brewery built near the outskirts of the city, near Weesperplein. Here, mostly bottom-fermented German-style beers were produced. The old brewery on Geldersekade closed in 1888, which meant the end of the old Haantjesbier. The name Haantjesbier was transferred to the new brewery’s pilsener, until the company closed its doors in 1917.[6]

Especially during the 19th century Haantjesbier was widely known in the Dutch Indies. In Malay language, it was called ‘Bier Ajam’: chicken beer.[5] Around 1850, De Haan (by that time called Haan & Sleutels) was one of the two biggest breweries of Amsterdam and the Netherlands as a whole. By 1868 however, they were facing competition from the quickly growing new industrial breweries that made Bavarian beer, like Amstel and Heineken. De Haan & Sleutels had to keep up with its time, and had a second brewery built near the outskirts of the city, near Weesperplein. Here, mostly bottom-fermented German-style beers were produced. The old brewery on Geldersekade closed in 1888, which meant the end of the old Haantjesbier. The name Haantjesbier was transferred to the new brewery’s pilsener, until the company closed its doors in 1917.[6]

So was there still a recipe, to enable us to taste the beer the Tachtigers once drank? Unfortunately, the archives of the original Haantjesbier brewery are lost. However, I had found a recipe for a Dutch ‘East Indies Beer’ from 1866. I suspected the author was the The Hague brewer Bernardus Marinus Perk, whose nephew was poet (and member of the Tachtigers group) Jacques Perk. So probably there was a Tachtigers connection after all.[7]

A beer with lots of hops, that a first boil had to be poured into a silver recipient, in which the proteins could sink to the bottom and then be taken out. After all, the less proteins, the less the beer could deteriorate during the journey. After fermentation, the beer had to be stored in wooden barrels that had been soaked in the taste of juniper berries, and a small amount of brandy was added, after which the beer was aged for eight to twelve months. And only then it was shipped.

A beer with lots of hops, that a first boil had to be poured into a silver recipient, in which the proteins could sink to the bottom and then be taken out. After all, the less proteins, the less the beer could deteriorate during the journey. After fermentation, the beer had to be stored in wooden barrels that had been soaked in the taste of juniper berries, and a small amount of brandy was added, after which the beer was aged for eight to twelve months. And only then it was shipped.

An interesting beer, but not one you make just like that on a rainy afternoon in your kitchen. Especially ageing the beer requires a lot of know-how, because it involves many hardly understood biological processes. But Stephen Grigg and his friend Gijs van Wiechen of the Kromme Haring brewery have that skill, and they have proven that with previous great keeping beers.

Friday 27 October promised to be a wonderful evening, at the Tropenmuseum theatre in Amsterdam, and I wasn’t disappointed. Theatre group Oude Koeien performed a play about the life of Willem Kloos, one of the Tachtigers, with a script by Simon Mulder. Right before the start, the Haantjesbier was presented. I had been invited to give a brief overview of the beer and its background, after which poet and actor (and former National Poet) Ramsey Nasr was presented with the first official bottle.

|

|

|

|

Just prior to the show I was already able to taste the beer, and I just happened to meet fellow beer writer Marco Daane there, who is currently working on a biography of another Tachtiger author, Jac. van Looy. Together we sampled this new Haantjesbier, and we both had the same opinion: this really is like it would have tasted in the 19th century. I’m not good at writing down tasting notes, but it was a wonderful aged beer with a great complex taste. This is historical beer as it should be: no concessions to quick delivery times or trendy hop varieties, but simply dead good.

For the moment the Kromme Haring‘s Haantjesbier is a one-off brew, so be quick to come to Utrecht to taste it at their brewpub from a robust 0,75 litre bottle. And for those interested in Dutch literature, keep an eye on Simon Mulder and his poetry festivals: this time they had an historical beer, but they regularly have events involving a very real absinth bar as well…

[1] Prof. Dr. P. de Rooy, ‘Bier, kunst en politiek: De Nieuwe Gids in Amsterdam’, in: Jaarboek Amstelodamum, nr. 81 (1989), p. 175-187.

[2] http://bierinnederland.blogspot.nl/2017/10/175-jaar-pilsener-en-140-jaar-nederlands.html

[3] De Tijd 11-1-1958.

[4] J. Gawronski, ‘Bier voor de VOC. De productie en inkoop in Amsterdam in het midden van de 18de eeuw’, in: Kistemaker en Van Vilsteren, Bier! Geschiedenis van een volksdrank, p. 132-145 Aegidius Daalmans, De nieuw hervormde genees-konst gebouwd op de gronden van het acidum en alcali, Amsterdam 1720, p. 103; Abraham Titsingh, Konst-broederlyke lessen of noodige aanmerkingen wegens de koortszen op schepen van oorlog, tot nut der heelmeesteren, Amsterdam 1742, p. 78.

[5] M.T.H. Perelaer, Baboe dalima: opium roman, deel 2, Rotterdam 1886, p. 249.

[6] Pim van Schaik en Kees Volkers, Ontdek de bieren van Amsterdam. Brouwerijen, biercafés en historie, Amsterdam 2013, p. 55.

[7] De praktische bierbrouwer, bewerkt door een oudbrouwer, Amsterdam 1866, p. 104-105. For my adaptation into a modern recipe, see my book: Roel Mulder, Verloren bieren van Nederland, Houten 2017, p. 153. For my argumentation that B.M. Perk is the author of De praktische bierbrouwer, see http://verlorenbieren.nl/verloren-bieren-47-de-praktische-bierbrouwer-1/ and http://verlorenbieren.nl/verloren-bieren-47-de-praktische-bierbrouwer-2/.

Leave a Reply