Caves: another lost Belgian beer

Time to look another long lost Belgian beer, this time from Lier, a nice old little town on the Nete river. It has quaint little streets in the beguinage, a beautiful old town hall, and a Medieval tower with an astronomical clock. Currently, it does not have its own brewery. It does however have a story to tell about historical beers.[1]

Time to look another long lost Belgian beer, this time from Lier, a nice old little town on the Nete river. It has quaint little streets in the beguinage, a beautiful old town hall, and a Medieval tower with an astronomical clock. Currently, it does not have its own brewery. It does however have a story to tell about historical beers.[1]

In the 1990s, Belgian historian Erik Aerts delved into Lier’s brewing industry, from the 14th until the early 19th century. The result was Het bier van Lier (‘The beer of Lier’), a very thorough book, though a slightly dry read if you’re a layman.[2] Interestingly, it gives an insight into an unexpected question: who actually taught the Belgians how to brew?

Already in its earliest days, Lier was home to brewers who used a herb mix called gruit to produce their tart beers that had a very short shelf life. But lo, during the 14th century the first hop beers arrived, from renowned beer producing cities like Hamburg in Northern Germany and later Haarlem in Holland, to the dismay of the local gruit brewers, who quickly saw themselves outcompeted. Therefore, around the year 1400 the people of Lier tried to brew with hops themselves, in the manner or Haarlem (‘na de wijse van Haerlam’). Reactions were mixed. A few decades later, when a new beer type called kuit arrived from Holland, they proceeded to imitate that, as exactly as possible. And there you go, this time they got it right, and Lier became a centre of beer production, basically by mimicking the Dutch brewing methods. However, it would take some time until they developed a successful beer style of their own: caves (pronounced, apparently, ‘kah – VESSE’).

In the late 17th century this beer first surfaced. ‘There, people brew a very good beer, commonly called Kaves of Lier, which is exported throughout the country, and that is drunk a lot in summer.’[3] It was a white-coloured wheat beer with a certain amount of oats in it, that was indeed popular in Brabant (which in this case means, the current provinces of Brabant and Antwerp) and Flanders (the provinces of East- and West-Flanders). In Gent, the people of Lier were even asked in 1721 to provide a certificate with their beer, because a lot of bad, foreign beers came to the city ‘under the name of beers of Lier’.[4] An ‘appellation contrôlée’ for beer, as early as the 18th century!

In the late 17th century this beer first surfaced. ‘There, people brew a very good beer, commonly called Kaves of Lier, which is exported throughout the country, and that is drunk a lot in summer.’[3] It was a white-coloured wheat beer with a certain amount of oats in it, that was indeed popular in Brabant (which in this case means, the current provinces of Brabant and Antwerp) and Flanders (the provinces of East- and West-Flanders). In Gent, the people of Lier were even asked in 1721 to provide a certificate with their beer, because a lot of bad, foreign beers came to the city ‘under the name of beers of Lier’.[4] An ‘appellation contrôlée’ for beer, as early as the 18th century!

There were to types of caves: a pale-coloured export version, and a yellow-coloured keeping version for use in Lier itself. One of the main factors in the success of caves was its ABV: apparently it was no less than 11.7%![5] The use of wheat, the most expensive type of grain, also placed caves in the category of a luxury beer. In the 19th century it all went downhill, presumably because of competition from white beers from Hoegaarden and Leuven. By the time French engineer Georges Lacambre recorded the brewing method for caves (see below), in 1851, he was already writing in the past tense.[6] Two decades later, the caves of Lier had completely disappeared.

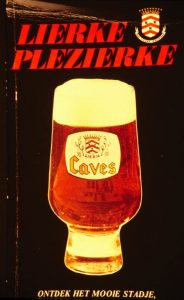

Yet, today you can once more drink a beer called ‘caves’ in Lier. A local guild called ‘Heren van Lier’ (‘Lords of Lier’) retraced a recipe in 1976 and has it brewed by the Verhaeghe brewery in Vichte (Western Flanders) ever since. However, it certainly is not an export beer anymore: the guild has stipulated that caves may only be served and drunk on Lier’s soil and nowhere else. If at any time this golden rule is broken, as was the case in Oostende in 2012, the guild’s representatives drop by with a jar of Lier soil to scatter it in the pub concerned, thus righting the wrong.[7]

Yet, today you can once more drink a beer called ‘caves’ in Lier. A local guild called ‘Heren van Lier’ (‘Lords of Lier’) retraced a recipe in 1976 and has it brewed by the Verhaeghe brewery in Vichte (Western Flanders) ever since. However, it certainly is not an export beer anymore: the guild has stipulated that caves may only be served and drunk on Lier’s soil and nowhere else. If at any time this golden rule is broken, as was the case in Oostende in 2012, the guild’s representatives drop by with a jar of Lier soil to scatter it in the pub concerned, thus righting the wrong.[7]

The current reconstruction may not be all that faithful: its ABV is only 5.8%, almost half of what it once must have been. Also, it is amber-coloured instead of pale white like export caves or yellow like the version drunk in Lier itself. In any case, to drink the current Lier version you’ll have to take a trip to Belgium, for the historical variant, you can brew it yourself. Here’s Georges Lacambre’s 1851 version.

Beers of Lier[8]

(…) The grains used for preparing these beers are well-germinated and moderately kilned barley, with wheat and oats mixed with the malt in a proportion of six parts of barley for one part of wheat and two of oats. According to dr. Vrancken [writing in 1829], these are the proportions used: for 50 kg of grains one obtains 100 litres of strong caves and 130 second-quality caves. This is, according to this author, how caves was brewed in his time.

One would pour the grains into the mash tun and for the variety that used to be exported to Flanders,[9] which was less coloured than the other one, they would first add lukewarm water to prepare the first mash, which was partly extracted with baskets and partly through the false bottom. A second mash was made with almost-boiling water, which together with the first mash made up the caves that was formerly exported to Flanders.

For the beer that was consumed locally, only the first mash was used; the second mash was used for a beer of inferior quality. For the latter type of brew, the temperature of the water used for the first mash was higher than for the export beer, which was paler.

When all the wort was united in the kettle, for the pale caves it was boiled for three hours with one third or half a kilogram of hops per 150 litres of wort, and for the locally consumed beer, the wort was boiled for six hours with half a kilogram of hops per 150 litres of wort.

After boiling, the wort was taken to the coolers and put in barrels still slightly lukewarm in winter, and as cold as possible in summer. Before putting in in barrels, a rather large amount of yeast was added, so that it would ferment promptly and would be drinkable after three to four days in summer and eight to ten days in winter, at least for the pale beer, which would generally be shipped once the main fermentation had ended, which is to say, no discernible yeast would still come out of the barrel.

When this beer was not shipped immediately after fermentation it could not be kept that well and did not become that clear; I have often observed the same thing for Leuven’s white beers, which also require shipment before secondary fermentation has ended, or at least before the yeast has completely sunk to the bottom.

The caves that used to be shipped to Flanders was then a kind of white beer while the one that is brewed for local consumption is a yellow beer that can be kept rather well for two to three months and that is rather easily cleared by isinglass after six weeks, while the first is drunk within two weeks in summer, never becomes clear, not even by use of isinglass or at least very imperfectly; this is another thing that it has in common with the beers of Leuven and Hoegaarden.

[1] This article was based on an earlier version in Dutch, https://verlorenbieren.nl/verloren-bieren-29-caves/.

[2] Erik Aerts, Het bier van Lier. De economische ontwikkeling van de bierindustrie in een middelgrote Brabantse stad (eind 14de – begin 19de eeuw), Brussels 1996.

[3] Aerts, Het bier van Lier, p. 122.

[4] Aerts, Het bier van Lier, p. 132.

[5] Aerts, Het bier van Lier, p. 220.

[6] Georges Lacambre, Traité complet de la fabrication de bières et de la distillation des grains, pommes de terre, vins, betteraves, mélasses, etc., Brussels 1851, p. 374-375.

[7] https://web.archive.org/web/20150607161819/http://www.herenvanlier.be/oostende-is-nu-liers-erfgoed

[8] Lacambre, Traité complet, p. 374-375.

[9] For this, read the current provinces of East- and West-Flanders.

Cartuyvels in 1879 talks about it too but not as a beer in the past.

Les matières farineuses employées dans cette ville pour la fabrication d’une bière mixte appelé cavesse, sont toujours l’orge fortement germée et modérément touraillée, le froment et l’avoine mélangés dans les proportions de 6 parties d’orge, 1 de froment et 2 d’avoine ;

50 kilogrammes de ces matières donnent 100 litres de cavesse forte et 130 litres de cavesse de seconde qualité.

Cette proportion est celle que renseigne La Cambre : à Lierre comme partout, l’avoine est aujourd’hui souvent hors d’usage à la cuve du brasseur et la formule a été modifiée en conséquence.

Pour préparer un brassin, on donne d’abord de l’eau tiède aux matières pour obtenir un premier métier qu’on enlève aux paniers, et par le double fond on fait une seconde trempe à l’eau presque bouillante qui, avec le premier métier, constitue la cavesse, sorte de bière blanche ou pale qu’on exportait jadis dans les Flandres. Quand on veut obtenir la cavesse jaune qu’on consomme dans la localité, on se sert du premier métier seul, le second sert à préparer

une qualité inférieure. L’eau de première trempe est à une température plus élevée que pour l’autre bière.

Quand tout le moût est réuni dans la chaudière pour la cavesse pâle, on lui fait subir une ébullition de 3 heures avec 350 à 500 grammes de houblon pour 150 litres de moût,

tandis que pour la cavesse jeune on fait bouillir vivement pendant 6 heures le liquide avec 300 grammes de houblon pour la même quantité de liquide.

Le moût, après la cuisson, est élevé sur les bacs, entonné légèrement tiède en hiver et le plus frais possible en été.

Avant cet entonnage on y mélange une assez forte proportion de levure qui la fait fermenter promptement et la rend potable au bout de 3 à 4 jours en été et de 8 à 10 en hiver.

From N. Basset 1868

Travail de cette bière, d’après Vrancken:

1° Introduction de la matière.

2° Première trempe à l’eau tiède.

3° Extraction par les paniers et le double fond.

4° Deuxième trempe à l’eau presque bouillante. Ces deux trempes réunies servaient à faire la bière d’exportation.

La cavesse forte était faite avec la première trempe et la seconde trempe donnait une bière faible.

5° Ébullition du moût avec le houblon, pendant trois heures et demie pour la cavesse pâle d’exportation, et pendant six heures pour la cavesse forte.

6° Envoi aux refroidissoirs. 7° Entonnage avec addition de levure et fermentation de trois à quatre jours. Consommation immédiate.

Les proportions employées sont de 1 de froment cru,6 de malt et 2 d’avoine.

50 kilogrammes de grain rendent 1 hectolitre de cavesse forte et 1,30 hl de petite bière.

Le rapport de production est de 2 litres de bière forte et 2,60l de petite bière par kilogramme de grain, soit en tout 4,60l.

Six parts barley, one of wheat and two of oats for a wort that was boiled six hours—it doesn’t *sound* particularly pale to me.

3Hrs to 3 1/2 for the pale

Has anyone brewed this or have a recipe that is scaled for home brewers?

Ben bezig met samenstellen van het recept (20 liter) voor thuisbrouwers.

Sorry, I could not understand that language.

I only have recipes for big batches from the old books.

But it could be easily scaled down with any beer recipe software.

Is there any information on the style with regard to yeast selection? Is this more of a Trappist style beer or a saison style? Smothering else? Clearly it will need to be alcohol tolerant. Thanks for any insights. Curt.