Berliner Alt: it sounds German, but it’s a Dutch lost beer

‘Do you know this beer style?’ Marco Lauret, brewer at Duits & Lauret, asked me. To his e-mail, he attached a jpg file of a label from a long closed brewery in the town of Culemborg, the Netherlands. A label for a beer called ‘Berliner Oud’. When I receive such a message, I always hope that it will lead to an ancient recipe being brewed again, so I thought: great, I’ll just dig up an old brewing instruction from Berlin, send it to Marco, and my job is done. But.. what exactly was this Berliner Oud?

‘Do you know this beer style?’ Marco Lauret, brewer at Duits & Lauret, asked me. To his e-mail, he attached a jpg file of a label from a long closed brewery in the town of Culemborg, the Netherlands. A label for a beer called ‘Berliner Oud’. When I receive such a message, I always hope that it will lead to an ancient recipe being brewed again, so I thought: great, I’ll just dig up an old brewing instruction from Berlin, send it to Marco, and my job is done. But.. what exactly was this Berliner Oud?

The old label Marco pointed my attention at, was from the Pauw (Peacock) brewery, owned by Gustaaf Hustinx. It was located in Culemborg, a town near the fortress of Everdingen where Duits and Lauret are currently brewing their wonderful beers. Gustaaf Hustinx (1885-1960), originally from, Maastricht, had bought the company in 1909 and sold it again in February 1913.[1] He may have sold it because he pursued a career in the army: he was summoned for active duty in the second regiment infantry at Den Bosch. After that, he moved to Venlo.[2]

The Pauw brewery was founded in the 19th century, in a 16th century monumental building on Grote Kerkstraat, in the heart of Culemborg’s historical centre. During the short period that Hustinx owned the brewery, he mainly produced bottom-fermented beer, like pilsner, light lager and bock.[3] And, evidently, Berliner Oud. ‘Oud’ is Dutch for ‘old’.

Hustinx produced German-style beers, and I figured it wouldn’t be difficult to find a recipe for such a Berliner Oud (or, in German, Berliner Alt) beer. After all, today the internet offers loads of digitised old books. Google Books contains scores of 19th century German brewing manuals that tell you how to brew Baireuther, Goslarisch, Kottbusser or Mannheimer beer. But no matter how I searched, no recipe for ‘Berliner Altbier’ or anything similar. Nor were there any advertisements or other mentions of such a beer. Well, except in Dutch sources. That raised my suspicion.

Hustinx produced German-style beers, and I figured it wouldn’t be difficult to find a recipe for such a Berliner Oud (or, in German, Berliner Alt) beer. After all, today the internet offers loads of digitised old books. Google Books contains scores of 19th century German brewing manuals that tell you how to brew Baireuther, Goslarisch, Kottbusser or Mannheimer beer. But no matter how I searched, no recipe for ‘Berliner Altbier’ or anything similar. Nor were there any advertisements or other mentions of such a beer. Well, except in Dutch sources. That raised my suspicion.

Berlin is of course mostly known for its Berliner Weisse, which is said to have been around since the 17th century and rose to prominence in the 19th century. So I asked Benedikt Koch, the expert on Weisse history, if he had ever heard of Berliner Alt. He hadn’t. He told me that there once existed a Berliner Braunbier, which was sweetened with sugar, but such a Braunbier is absent from Dutch sources. Also, Braunbier wasn’t exactly an ‘alt’ beer: it was often delivered to pubs when main fermentation was still going.[4]

Berlin is of course mostly known for its Berliner Weisse, which is said to have been around since the 17th century and rose to prominence in the 19th century. So I asked Benedikt Koch, the expert on Weisse history, if he had ever heard of Berliner Alt. He hadn’t. He told me that there once existed a Berliner Braunbier, which was sweetened with sugar, but such a Braunbier is absent from Dutch sources. Also, Braunbier wasn’t exactly an ‘alt’ beer: it was often delivered to pubs when main fermentation was still going.[4]

So if Berliner Alt was not to be found in Germany itself, what’s the deal? It turned out that only in the Netherlands, there must have existed a Berliner Alt or Oud at some point. As far as I could find, it all started on the 1st of November 1886, when the State Gazette announced the official registration of a beer label by a certain P.A. Roelofs, publican at café Helvetia on Spoorstraat in Nijmegen. The label, of which no image has survived, sported a portrait of the mythical beer king Cambrinus with the words ‘Berliner Alt’ and ‘trade-mark’ (in English), along with the letters ‘F.L.’ and Roelofs’ initials. The label was to be used on barrels and bottles, but I have found no evidence that Roelofs has actually produced or sold such a beer.[5]

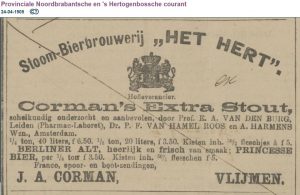

A few weeks later, Berliner Alt surfaced somewhere else. The Corman brewery in the Brabant village of Vlijmen, a company known for its top-fermented beer such as extra stout and pale ale, advertised its ‘Berliner Alt, being hearty and pleasant, quickly foaming in the bottle and can also be served from the barrel.’[6]

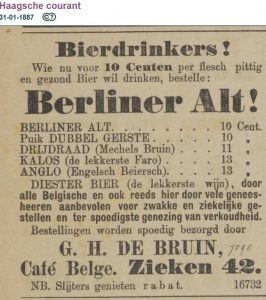

Within a few months Berliner Alt could be found all over the country. Beer merchants in Zaltbommel, Delft and Zwolle sold it, while the Café Belge in The Hague recommended this ‘very powerful’ brew as follows: ‘Beer drinkers! Those who want to drink a bottle of hearty and healthy beer at a price of 10 cents, should order: Berliner Alt!’[7] Probably as an imitation of Corman, it was also brewed by Junghuhn & co in Breda, by Rutten in Maastricht and by De Meiboom in Vlissingen.[8]

Within a few months Berliner Alt could be found all over the country. Beer merchants in Zaltbommel, Delft and Zwolle sold it, while the Café Belge in The Hague recommended this ‘very powerful’ brew as follows: ‘Beer drinkers! Those who want to drink a bottle of hearty and healthy beer at a price of 10 cents, should order: Berliner Alt!’[7] Probably as an imitation of Corman, it was also brewed by Junghuhn & co in Breda, by Rutten in Maastricht and by De Meiboom in Vlissingen.[8]

In the years after that, it was mainly Corman in Vlijmen who brewed it. He was still advertising it by 1905, and then from 1905 to 1915 a certain C. van der Wal in Rotterdam was ‘main agent’ for Berliner oud beer.[9] Newspaper ads tell us that also the Van Vollenhoven brewery in Amsterdam must have made it, and there’s a label for Berliner Alt from De Valk brewery in Eindhoven.[10]

And now of course, the big question: what was the beer like? Almost all breweries who produced it, were mainly top-fermenting. Furthermore, several ads claim it was a beer ‘like stout’.[11] Its price was in the middle range however, which means that it was cheaper than actual stout, which was a relatively heavy beer at the time. I don’t think Berliner Alt was derived from the Altbier of Düsseldorf in Germany, which was as good as unknown in the Netherland. The city of Venlo had an Altbier of its own, which may have been related (but that’s something for another article).

So what to make of this? My conclusion is that Berliner Alt probably was a fantasy style, developed as an attempt by small Dutch brewers to cash in on the popularity of German beer. A top-fermented, dark-coloured response to the brown Bavarian beers that were popular at that moment. All in all, it never really took off.

So what to make of this? My conclusion is that Berliner Alt probably was a fantasy style, developed as an attempt by small Dutch brewers to cash in on the popularity of German beer. A top-fermented, dark-coloured response to the brown Bavarian beers that were popular at that moment. All in all, it never really took off.

Last question: how does the Berliner Oud made by Hustinx in Culemborg fit into this? Hustinx mainly produced bottom-fermented beer. Maybe his Berliner Oud was a bottom-fermented variant on the products of Corman and others. Unfortunately, we will never know. In 1913, Hustinx sold his brewery to one H. van den Heuvel, who closed it for good in 1916. The building on Grote Kerkstraat was then used by a coal merchant, furniture factory, ice factory and as a warehouse for vegetables and fruit. Once the building had been worn out completely, it was restored. During restauration, a few old bottles and labels were found.[12] Apart from that, nothing that could tell us anything about the daily affairs at the brewery has survived.

[1] Culemborgsch Nieuws- en Advertentieblad 1-1-1909, 15-3-1913; Culemborgsche courant 6-2-1913.

[2] Information courtesy of Nico Luttik, who contributed several ideas to this article.

[3] bieretiketten.nl; Culemborgsch Nieuws- en Advertentieblad 20-1-1912.

[4] https://www.beeradvocate.com/articles/10019/berliner-braunbier/

[5] Nederlandsche Staatscourant 1-11-1886.

[6] Het nieuws van den dag 29-11-1886.

[7] Bommelsche Courant 30-11-1887; Delftsche courant 8-7-1887; Nieuwe Tielsche Courant 1-10-1887; Haagsche courant 31-1-1887.

[8] De Tijd 7-10-1887; Nieuwe Tielsche Courant 17-9-1887; Zierikzeesche Courant 12-12-1888.

[9] Provinciale Noordbrabantsche en ‘s Hertogenbossche courant 24-4-1905; Rotterdamsch nieuwsblad 15-6-1905, 10-12-1915.

[10] Zierikzeesche Courant 24-5-1900; bieretiketten.nl.

[11] Haagsche courant 29-4-1889, 28-7-1890, 26-6-1891, 14-1-1892.

[12] https://www.voetvanoudheusden.nl/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=60:dedekenij&catid=16&Itemid=45

Leave a Reply