A small history of Flemish old brown (and red) – 2

‘The double beer of Oudenaarde,’ wrote journalist and author Karel van de Woestijne in 1906, may not be as famous as its gothic city hall, but those who know it ‘compare it to the best wines of Burgundy. To them, Oudenaarde’s beer compares to ordinary beer as Musigny does to the most common of table wines.’ Those who were familiar with Oudenaarde’s beer, turned their nose up at gueuze-lambic and other beer types, when ‘lying in its basket, a bottle of Oudenaarde’ was served. In Gent, where it was particularly popular, there were people who fell out with each other over the question which of the two main Oudenaarde brands were the best: Felix or Liefmans.[1]

‘The double beer of Oudenaarde,’ wrote journalist and author Karel van de Woestijne in 1906, may not be as famous as its gothic city hall, but those who know it ‘compare it to the best wines of Burgundy. To them, Oudenaarde’s beer compares to ordinary beer as Musigny does to the most common of table wines.’ Those who were familiar with Oudenaarde’s beer, turned their nose up at gueuze-lambic and other beer types, when ‘lying in its basket, a bottle of Oudenaarde’ was served. In Gent, where it was particularly popular, there were people who fell out with each other over the question which of the two main Oudenaarde brands were the best: Felix or Liefmans.[1]

After a somewhat uncertain start, the old brown beer of Flanders had acquired some fame by the end of the 19th century, and as Van de Woestijne’s words clearly testify, the beers of the East-Flemish town of Oudenaarde were among the most well-known varieties. ‘It is the strongest and headiest. It is darker than ordinary beer and can be kept indefinitely,’ a Charleroi newspaper wrote in 1904. ‘No expenses are spared on Bavarian hops, which are better than those of Aalst. (…) A barrel of Oudenaarde costs 25 francs per 180 litres, from the renowned breweries Liefmans or Felix.’[2] A series of advertisements from 1909 tells us that Liefmans’ beer was also available in various restaurants and cafés in Brussels.[3]

After a somewhat uncertain start, the old brown beer of Flanders had acquired some fame by the end of the 19th century, and as Van de Woestijne’s words clearly testify, the beers of the East-Flemish town of Oudenaarde were among the most well-known varieties. ‘It is the strongest and headiest. It is darker than ordinary beer and can be kept indefinitely,’ a Charleroi newspaper wrote in 1904. ‘No expenses are spared on Bavarian hops, which are better than those of Aalst. (…) A barrel of Oudenaarde costs 25 francs per 180 litres, from the renowned breweries Liefmans or Felix.’[2] A series of advertisements from 1909 tells us that Liefmans’ beer was also available in various restaurants and cafés in Brussels.[3]

Meanwhile, also Rodenbach from the West-Flemish town of Roeselare was expanding. From 1900 onwards their ‘Vieille brune des Flandres’ is mentioned in various newspaper adverts in places like Tournai, Antwerp, Gent and Ieper.[4] In 1894 they had already been one of the participants at the World Fair in Antwerp, where they won a gold medal, and in 1900 they did the same in Paris.[5]

Speaking of fairs, in 1903 steam brewery Sint-Joris from Beerst near Diksmuide received awards for its brown bottled beer at exhibitions in Gent and Marseille. They added: ‘This beer is at least two years old, robust and recommended by doctors of medicine.’[6] In 1907 M. Croigny from Lo won a gold medal for his old beer at a competition in Oostende, and in 1910 it was the Feys-Callewaert brewery from Roesbrugge that triumphed with a gold medal at the World Fair in Brussels with their ‘forte brune’.[7]

Speaking of fairs, in 1903 steam brewery Sint-Joris from Beerst near Diksmuide received awards for its brown bottled beer at exhibitions in Gent and Marseille. They added: ‘This beer is at least two years old, robust and recommended by doctors of medicine.’[6] In 1907 M. Croigny from Lo won a gold medal for his old beer at a competition in Oostende, and in 1910 it was the Feys-Callewaert brewery from Roesbrugge that triumphed with a gold medal at the World Fair in Brussels with their ‘forte brune’.[7]

‘Oudenaarde is a city of about 7000 inhabitants, with a wonderful old city hall,’ a German soldier wrote home, during the First World War. ‘We ate quite well here, and most importantly, we drank Oudenaarde’s double beer, the most historical and most beautiful that is to be had in Belgium.’ He added that it needed to be aged for at least five years.[8]

This German enthusiasm can however not conceal how disastrous the years 1914-1918 were for Belgium, and for its brewers. Many breweries saw their copper kettles and equipment taken away for use by the German weapon industry, and many breweries in Flanders were ravaged by the violence of the war. The buildings of Rodenbach in Roeselare and those of Liefmans in Oudenaarde were also heavily damaged. Partly as a result of this, but also because of a lack of space, Liefmans built a new brewery outside the city centre in 1923. The next year, Liefmans was the 21st biggest brewery in Belgium by production volume, with over a million kilograms of malt used that year.[9]

This German enthusiasm can however not conceal how disastrous the years 1914-1918 were for Belgium, and for its brewers. Many breweries saw their copper kettles and equipment taken away for use by the German weapon industry, and many breweries in Flanders were ravaged by the violence of the war. The buildings of Rodenbach in Roeselare and those of Liefmans in Oudenaarde were also heavily damaged. Partly as a result of this, but also because of a lack of space, Liefmans built a new brewery outside the city centre in 1923. The next year, Liefmans was the 21st biggest brewery in Belgium by production volume, with over a million kilograms of malt used that year.[9]

We actually don’t know that much about the exact properties of Flemish old brown during those years. In 1913 the alcohol content of an Oudenaarde brown beer was found to be 4.14% ABV, while a brown beer from Zottegem was at 4.43% ABV.[10] Hendrik Verlinden, a brewer from Brasschaat, published a recipe for Oudenaarde beer in 1935, with only 66% malt, the remainder being rice, sugar, glucose, colourant and syrup.[11] The question is of course, how representative this really was.

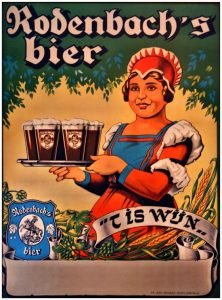

As for the taste, Karel van de Woestijne compared it to wine, or as he called Oudenaarde in 1914: ‘the Chambertin of beers’.[12] Rodenbach didn’t shy away from mentioning its wine-like taste, as becomes clear from the slogan they launched in the 1930s: ‘It’s wine!’ It was accompanied by a cheerful lady in traditional costume, who was known as ‘Big Bertha’.[13]

As for the taste, Karel van de Woestijne compared it to wine, or as he called Oudenaarde in 1914: ‘the Chambertin of beers’.[12] Rodenbach didn’t shy away from mentioning its wine-like taste, as becomes clear from the slogan they launched in the 1930s: ‘It’s wine!’ It was accompanied by a cheerful lady in traditional costume, who was known as ‘Big Bertha’.[13]

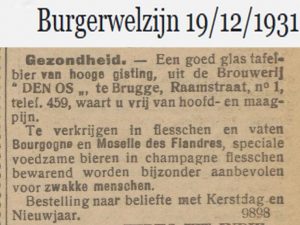

Another brewery that was most happy to compare its old beer to wine was Den Os (‘The Ox’) in Bruges, which launched its ‘Bourgogne des Flandres’ in 1911. ‘Bourgogne’ is not a reference to the time the dukes of Burgundy ruled Bruges, as Dutch Wikipedia claims, but alludes to Burgundy wine. In the 1920s, Den Os introduced a short-lived blonde sibling called ‘Moselle des Flandres’. By ‘Moselle’ they meant Mosel, a well-known wine from Germany named after the river with the same name.[14]

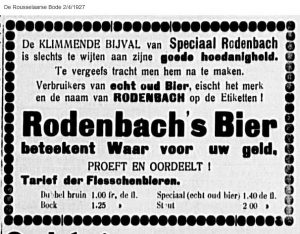

Interestingly, in the 1920s and 1930s Rodenbach too went down the path of diversification. As early as 1894, Rodenbach had started producing blonde uitzet, and in 1926 their newspaper adverts show not only ‘double brown’ and ‘Special (real old beer)’ but also a bock and a stout.[15] Another Rodenbach beer, which probably endured after the Second World War, was ‘Mandel ale’, an brew in English pale ale fashion. Somewhere during the 1960s and 1970s, they even produced a gueuze for a while, called ‘Gueuze Saint-Georges’. Probably in the early 1970s, they added the Rodenbach Grand Cru to their range of products.

Interestingly, in the 1920s and 1930s Rodenbach too went down the path of diversification. As early as 1894, Rodenbach had started producing blonde uitzet, and in 1926 their newspaper adverts show not only ‘double brown’ and ‘Special (real old beer)’ but also a bock and a stout.[15] Another Rodenbach beer, which probably endured after the Second World War, was ‘Mandel ale’, an brew in English pale ale fashion. Somewhere during the 1960s and 1970s, they even produced a gueuze for a while, called ‘Gueuze Saint-Georges’. Probably in the early 1970s, they added the Rodenbach Grand Cru to their range of products.

At Liefmans in Oudenaarde, the product range was expanded considerably. They produced gersten (‘barley beer’), export, ‘dark ale’ (in English on the original labels) and an abbey-style beer, ‘Abdij van Maegdendaele’. Things took a very profitable turn under the rightly famous ‘Madame’ Rosa-Blancquaert-Merckx, who started out in 1946 as a secretary to the manager, but soon she started running the entire place. She also had her influence on the beer’s taste. She thought the Oudenaarde beer Liefmans was brewing at the time was ‘unbearably sour’. She told the brewers, ‘this is a beer for the elderly, but now the war is over. Young people are starting to flock to the pubs, where they drink Coca-Cola and other sweet drinks. They are not going to like this beer.’ From then on, Liefmans made its beer mellower and rounder, and sales went through the roof.[16]

Liefmans’ luxury beer Goudenband was originally called ‘IJzerenband’ (‘Iron band’), after the metal hoops that kept the wooden barrels together. They were forced to change the name because some other brewer had already claimed it. Another success story for Liefmans was their kriek, and other fruit beers would follow.

Liefmans’ luxury beer Goudenband was originally called ‘IJzerenband’ (‘Iron band’), after the metal hoops that kept the wooden barrels together. They were forced to change the name because some other brewer had already claimed it. Another success story for Liefmans was their kriek, and other fruit beers would follow.

Rodenbach wasn’t impervious to the changing tastes of post-war drinkers either. ‘Rodenbach softens its taste’, headlines told in 1974. After all, ‘in the past few years, the consumer’s taste seems to have shifted.’ After a long trajectory of experimentation, tasting panels and a fair amount of intuition, the brewing team, led by J. Lambert and C. Steurbaut, arrived at a ‘new balance’. The brewers reassured the public that the beer had not been made sweeter, they had just lowered its acidity. The Rodenbach Grand Cru was ‘softened’ in a similar way.[17] The need for innovation lingered: in 1986 they introduced the cherry beer Rodenbach Alexander, which was later succeeded by the less successful fruit beer Redbach and in 2014 by the Rodenbach Rosso. The Alexander was revived in 2016.

As for Bourgogne des Flandres, Den Os brewery in Bruges closed its doors in 1957, and production of Bourgogne des Flandres moved to the Verhaeghe brewery in Vichte. Around 1990, Timmermans in Itterbeek got the gig (after which Verhaeghe developed its own version, called Duchesse de Bourgogne). Since 2015, some of the production moved back to Bruges. And if you think about it, today’s blonde variety of Bourgogne des Flandres is really a reincarnation of the Moselle des Flandres from the 1920s.

As for Bourgogne des Flandres, Den Os brewery in Bruges closed its doors in 1957, and production of Bourgogne des Flandres moved to the Verhaeghe brewery in Vichte. Around 1990, Timmermans in Itterbeek got the gig (after which Verhaeghe developed its own version, called Duchesse de Bourgogne). Since 2015, some of the production moved back to Bruges. And if you think about it, today’s blonde variety of Bourgogne des Flandres is really a reincarnation of the Moselle des Flandres from the 1920s.

All in all, the biggest producers of Flemish old brown were going through a rough patch in the 1980s and 1990s. Liefmans was taken over by the Riva brewery in 1990, and after a bankruptcy it is now owned by Duvel Moortgat. Rodenbach was acquired by Palm in 1998. There is a certain international interest in Flemish old beer, but in Belgium itself the number of drinkers seems to be steadily declining. Let’s hope it will nevertheless have a bright future. Luckily, a number of small, independent brewers are still producing it as well.

As for the history of Flemish old brown, as we’ve seen this beer type doesn’t seem to be all that old. The problem is that the sources are rather fragmentary. My articles can only be a starting point, giving an outline of what I’ve found so far. Hopefully, more research, for instance in brewery archives, will shed more light on how and when this wonderful beer type actually came into being.

[1] Karel van de Woestijne, Verzameld journalistiek werk. Deel 1. Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant juli 1906 – juni 1907, Gent 1986, p. 274.

[2] Gazette de Charleroi 12-10-1904.

[3] Le patriote 22-8-1909, 14-10-1909; Le soir 19-8-1909, 20-8-1909, 13-9-1909, 7-10-1909, 27-10-1909.

[4] Het weekblad van IJperen 30-6-1900; Gazet van Antwerpen 24-2-1907; De Vlaamsche strijd 1-2-1908; Le courrier de l’Escaut 25-6-1908.

[5] Exposition Universelle d’Anvers 1894. Catalogue officiel général. Préliminaires, section Belge, sections spéciales, Brussels 1894, p. 178; Exposition universelle internationale de 1900 à Paris. Rapports du jury international. Groupe X – Aliments, deuxième partie, classes 60 à 62, Paris 1902, p. 515.

[6] De gazette van Rousselare 27-6-1903, 19-1-1907.

[7] De Poperinghenaar 25-8-1907 (thanks Chris Vandewalle); Le progrès 23-10-1910; De Poperinghenaar 9-7-1911.

[8] Charlotte Cappelle, Bruin. De geschiedenis van het brouwen in en rond Oudenaarde sinds 1357, Oudenaarde 2010, p. 71.

[9] De volksstem 29-1-1925.

[10] A.J.J. Vandevelde, ‘Leidraad voor lessen over de voeding van den mensch, voor hooger huishoudkundig onderwijs’, in: Verslagen en mededelingen van de Koninklijke Vlaamse Academie voor Taal- en Letterkunde, 1921, p. 361-445, here p. 425.

[11] Hendrik Verlinden, Leerboek der gistingsnijverheid uit de praktijk en voor de praktijk, Brecht 1933, p. 150.

[12] Karel van de Woestijne, Verzameld journalistiek werk. Deel 1. Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant juli 1906 – juni 1907, Gent 1986, p. 274; Karel van de Woestijne, Verzameld journalistiek werk. Deel 7. Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant november 1913 – maart 1915, Gent 1991, p. 273.

[13] Proost! Bier uit Roeselaarse brouwerijen. Lokale brouwerijen in oude beelden, themanummer van Oud Rousselare. Magazine van de dienst Statisch Archief Roeselare, volume 2012 nr. 2., p. 21, 26.

[14] La Flandre maritime 8-4-1928.

[15] Michel de Bruyne, De Rodenbachs van Roeselare, Antwerpen/Roeselare 1986, p. 228; De Rousselaarse bode 25-12-1926.

[16] Sofie Vanrafelghem, Bier, vrouwen weten waarom, Leuven 2013, p. 44.

[17] Het wekelijks nieuws 6-9-1974.

Leave a Reply