A small history of Flemish old brown (and red) – 1

On November 23 in the year 1877 there a very tragic accident took place in a brewery in the town of Geraardsbergen in the province of East-Flanders. One of the workers was cleaning a large vat that had been used or making old beer. Suddenly, he was overwhelmed by the vapours emanating from the yeast on the bottom of the vat, and he about to suffocate. Brewer Emile Vande Maele quickly jumped into the vat to save his unfortunate employee. The other workers tried to stop him, but it was too late. Vande Maele too couldn’t get air and choked. From everywhere people rushed forward to help, but there was so much carbon dioxide in the air that even the lamps held above the vat extinguished several times. In the end, the vat had to be chopped into pieces to get the bodies out.[1]

On November 23 in the year 1877 there a very tragic accident took place in a brewery in the town of Geraardsbergen in the province of East-Flanders. One of the workers was cleaning a large vat that had been used or making old beer. Suddenly, he was overwhelmed by the vapours emanating from the yeast on the bottom of the vat, and he about to suffocate. Brewer Emile Vande Maele quickly jumped into the vat to save his unfortunate employee. The other workers tried to stop him, but it was too late. Vande Maele too couldn’t get air and choked. From everywhere people rushed forward to help, but there was so much carbon dioxide in the air that even the lamps held above the vat extinguished several times. In the end, the vat had to be chopped into pieces to get the bodies out.[1]

This deadly incident in Geraardsbergen is not only tragical, it is also one of the earliest solid pieces of evidence that I could find for the existence of the beer that I was looking for: Flemish old brown. A wonderful, freshly tart beer type that nowadays in the province of East-Flanders is mainly made around the city of Oudenaarde. In West-Flanders it is produced in various places, with the Rodenbach brewery in Roeselare in the middle, both literally and figuratively. A beer that is made by having it rest one of more years in large vats and then mixing it with young beer. In West-Flanders, those vats are generally made of wood (and today, some people therefore prefer to call it red or red-brown beer), in East-Flanders they are nowadays often made of stainless steel.[2]

This deadly incident in Geraardsbergen is not only tragical, it is also one of the earliest solid pieces of evidence that I could find for the existence of the beer that I was looking for: Flemish old brown. A wonderful, freshly tart beer type that nowadays in the province of East-Flanders is mainly made around the city of Oudenaarde. In West-Flanders it is produced in various places, with the Rodenbach brewery in Roeselare in the middle, both literally and figuratively. A beer that is made by having it rest one of more years in large vats and then mixing it with young beer. In West-Flanders, those vats are generally made of wood (and today, some people therefore prefer to call it red or red-brown beer), in East-Flanders they are nowadays often made of stainless steel.[2]

But how old exactly is this beer type? That’s what I wanted to know. As it turned out, there is astonishingly little to be found on this subject. There are plenty of books and booklets on the beer history of places like Oudenaarde, Geraardsbergen, Roeselare, Ieper, Bruges and Gent. There is also some literature on various breweries, such as the series of booklets on breweries in the Westhoek region issued by museum De Snoek, a historical brewery and malthouse.

But how old exactly is this beer type? That’s what I wanted to know. As it turned out, there is astonishingly little to be found on this subject. There are plenty of books and booklets on the beer history of places like Oudenaarde, Geraardsbergen, Roeselare, Ieper, Bruges and Gent. There is also some literature on various breweries, such as the series of booklets on breweries in the Westhoek region issued by museum De Snoek, a historical brewery and malthouse.

However, none of these books has anything meaningful to say about Flemish old brown as a beer type before, say, 1850. Of course, before that there were plenty of breweries in Flanders[3], but there’s little evidence that they produced old beer. East-Flanders was primarily known for its uitzet, a blond or amber top-fermented beer that was drunk fresh.

There’s only one source that breaks the silence: Leuven-based doctor of medicine Jean-Baptiste Vrancken, who wrote a treatise on various Belgian beers in 1829. Right at the bottom of a five-page section on uitzet, Vrancken adds the following: ‘In Flanders, there is also made a brown, dark-coloured beer, that sears the palate and tightens the throat. It is made of kilned malt, without any other grains. It is boiled in open kettles for 20 to 30 hours.’[4] And that’s all. There’s nothing on any form of maturing. A 1839 print that shows various Belgian beer types personified as merry drinkers (including ‘Père Faro’, ‘Susse Lambic’, etc.), features a ‘Brown Bacchus’ from Ieper.[5] That’s not very enlightening, either.

There’s only one source that breaks the silence: Leuven-based doctor of medicine Jean-Baptiste Vrancken, who wrote a treatise on various Belgian beers in 1829. Right at the bottom of a five-page section on uitzet, Vrancken adds the following: ‘In Flanders, there is also made a brown, dark-coloured beer, that sears the palate and tightens the throat. It is made of kilned malt, without any other grains. It is boiled in open kettles for 20 to 30 hours.’[4] And that’s all. There’s nothing on any form of maturing. A 1839 print that shows various Belgian beer types personified as merry drinkers (including ‘Père Faro’, ‘Susse Lambic’, etc.), features a ‘Brown Bacchus’ from Ieper.[5] That’s not very enlightening, either.

The first description that seems to set us on the right track can be found with brewing engineer Georges Lacambre, who wrote a well-known reference work on Belgian brewing. In his book, he describes the ‘bières brunes de Flandres’ that were generally made of barley only, and of which the brewing process was similar to that of uitzet, but with darker malt. Also, it was boiled longer and more vehemently: usually 15 to 18 hours, sometimes even 20 hours. Lacambre wasn’t fond of its taste: ‘bitter, rough and somewhat astringent.’ Apparently, local drinkers enjoyed it this way. Its gravity could vary, but usually 40 to 45 pounds of malt were used per hectolitre of beer. Usually, the beer was only fit to drink after two or three months.[6]

Lacambre still doesn’t tell us much, actually. Which is rather astonishing, knowing that by marriage he was related to the Rodenbach brewery’s owners. His wife’s aunt was Regina Wauters, the sturdy brewster that ran her husband Pedro Rodenbach’s brewery with firm hand. Moreover, that same Pedro Rodenbach had been one of the witnesses at Lacambre’s marriage in 1840.[7] If you take that into account, it is all the more remarkable how little Lacambre had to say on Flemish brown beer.

Lacambre still doesn’t tell us much, actually. Which is rather astonishing, knowing that by marriage he was related to the Rodenbach brewery’s owners. His wife’s aunt was Regina Wauters, the sturdy brewster that ran her husband Pedro Rodenbach’s brewery with firm hand. Moreover, that same Pedro Rodenbach had been one of the witnesses at Lacambre’s marriage in 1840.[7] If you take that into account, it is all the more remarkable how little Lacambre had to say on Flemish brown beer.

Almost thirty years later, in 1879, brewing scientists Cartuyvels and Stammer published their brewing manual, but on the brown beer of Flanders they had little to tell except repeating Lacambre almost verbatim.[8] Again, it’s striking how little there can be found on old brown beer. It seems quite plausible that in some form it must have been around during the first half of the 19th century, taking into account that aged beer gained so much popularity in other countries and regions at the time. The sources pose a problem too: Belgians drank relatively large amounts of beer, so generally the brewers had no problem selling what they produced. There was little need to advertise their beer in newspapers. Little beer was ever bottled, it was mostly sold in vats, so no labels have been preserved. In Belgium, bottled beer only really became popular after the First World War. The lack of sources therefore provides us with a somewhat distorted image of reality.

An early example is an auction of wines and beers in Bruges in 1837, were about 200 tuns of beers were on sale, 18 months old.[9] So much old beer can hardly be a coincidence, but it’s hard to connect it to any general trend of the time. In 1866 beer from Oudenaarde was advertised in Brussels and in 1869 in Gent.[10] In 1877 there was the unfortunate event in Geraardsbergen mentioned previously. It seems however that Flemish old brown only experienced a breakthrough after that.

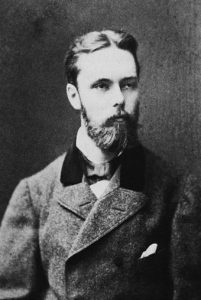

A brewery that doubtlessly played a role in that, even if it’s hard to say what role exactly, is Rodenbach from Roeselare. According to the available literature, it was young Eugène Rodenbach who around the year 1875 worked as an apprentice in England, to ‘study English brewing methods more carefully’. In 1878 he officially became partner in the family’s brewery.[11] As the story goes, he significantly improved the production process with his English know-how, or he may even have introduced the well-known large wooden vats at the brewery, today also known as ‘foeders’.[12] Unfortunately, this has not been the subject of extensive study, nor has anyone published anything on this.

A brewery that doubtlessly played a role in that, even if it’s hard to say what role exactly, is Rodenbach from Roeselare. According to the available literature, it was young Eugène Rodenbach who around the year 1875 worked as an apprentice in England, to ‘study English brewing methods more carefully’. In 1878 he officially became partner in the family’s brewery.[11] As the story goes, he significantly improved the production process with his English know-how, or he may even have introduced the well-known large wooden vats at the brewery, today also known as ‘foeders’.[12] Unfortunately, this has not been the subject of extensive study, nor has anyone published anything on this.

In any case, Rodenbach, one of the larger breweries for its day, was already going strong for decades. As early as 1837, a steam engine was huffing and puffing on the premises. In 1864 the brewery was substantially enlarged with a new brewing room and malthouse. Production was then at 6,000 hectolitres, and would rise to 15,000 hl in 1877 and 23,500 hl in 1888.[13] Unfortunately, the energetic Eugène Rodenbach would die in 1889, 39 years old. After that, his father Edward had to take charge again.

Elsewhere in Flanders too, there were signs that old brown beer was becoming popular. Brewer Louis Verlende from the West-Flemish town of Lo remembered that his father used a lot of old beer around the year 1900, partly to extend the shelf life of young beer in summer. ‘Also the beer drinkers’ taste, especially during the summer, was oriented towards old beer that we made by adding 10 to 15 litres of old beer per barrel. That acid taste apparently was to their liking and such beer certainly defeated their thirst very well. At haymaking time, a lot of old beer was demanded from De Fintele, for the haymakers.’ The farmers also enjoyed old beer during harvest.[14]

Brewer Verlende kept wine barrels of 600 to 700 litres in a cellar in a barn built in 1884, and in 1900 another building with vats was added. Moreover, Verlende had a cellar dug beneath his private home, with the purpose of putting vats there too. That proved to be a miscalculation: due to its weak foundations, the house almost collapsed. The rising popularity of old beer sometimes had dangerous consequences!

Brewer Verlende kept wine barrels of 600 to 700 litres in a cellar in a barn built in 1884, and in 1900 another building with vats was added. Moreover, Verlende had a cellar dug beneath his private home, with the purpose of putting vats there too. That proved to be a miscalculation: due to its weak foundations, the house almost collapsed. The rising popularity of old beer sometimes had dangerous consequences!

Another peek behind the scenes can be gotten at the Blanquaert brewery in the East-Flemish village of Schoonaarde, on the Schelde river. There, a booklet with notes from the period 1872-1907 has been preserved. They made four types of beer there. For instance, on the first of January 1888 they had 457 barrels of beer in stock, of which 126 barrels of ‘ongedreven’ (‘undriven’) beer, 177 dobbel (‘double’) beer, 120 barrels of ‘besnijbier’ (‘blending beer’) and 34 barrels of fresh beer. With these beers, they would make various blends, depending on the customer or the village it was sent to. The village of Oordegem would receive a different mix than Kalken or Smetlede. Interestingly, the raw materials used were hardly all from the region. They used things like malt from the Danube basin, rice and Bavarian hops.[15]

During this period, the late 19th century, Flemish old brown clearly gained popularity. A few breweries that still exist today, such as Verhaeghe, Vander Ghinste and Roman were already producing it at that time. In the next article, we will look at Flemish old brown in the 20th century.

[1] Gazette van Brugge 28-11-1877; Burgerwelzijn 28-11-1877; De Westvlaming 29-11-1877.

[2] In the remainder of this article, I will just call it Flanders brown or Flanders old brown. The name ‘red’ or ‘red-brown’ was only invented by Michael Jackson in the 1970s and came into local usage only recently.

[3] In this article, when I speak of Flanders, I mean both the provinces of East- and West-Flanders; I’m not referring to Dutch-speaking Belgium as a whole.

[4] Jean Baptiste Vrancken, ‘Antwoord op vraag 81’, in: Nieuwe verhandelingen van het Bataafsch Genootschap der Proefondervindelijke Wijsbegeerte te Rotterdam, Rotterdam 1829, p. 200.

[5] Zie bv. Michael Jackson, Spectrum bieratlas, Maarssenbroek 1977, p. 112-113.

[6] Georges Lacambre, Traité complet de la fabrication de bières et de la distillation des grains, pommes de terre, vins, betteraves, mélasses, etc., Brussels 1851, p. 312-313.

[7] Georges Lacambre married Hyacinthe Euphrosine Anchiaux in 1840 in Leuven. More on Lacambre will follow in an upcoming article.

[8] Jules Cartuyvels and Charles Stammer, Traité complet théorique et pratique de la fabrication de la bière et du malt, Brussels / Liège 1879, p. 411.

[9] Gazette van Brugge 12-6-1837.

[10] L’echo du parlement 18-11-1866; Le bien public 3-6-1869.

[11] Michel de Bruyne, De Rodenbachs van Roeselare, Antwerp/Roeselare 1986, p. 219-220. Thanks to Marco Daane for sharing his thoughts on Rodenbach’s history with me.

[12] ‘Foeders’ originally was not an actual Dutch word. In official Dutch, a large (wine) barrel was traditionally called a ‘voeder’ with a v. The term ‘foeder’ with an f probably comes from French ‘foudre’. On a side note, Rodenbach’s management was French-speaking. Up until at least the 1950s, incoming letters in Dutch had to be translated into French so the managers could read it. Cf. Frank Develtere, De passie van de brouwer. De geschiedenis van de Meulebeekse brouwerij Vondel, Meulebeke 2015, p. 122.

[13] De Bruyne, De Rodenbachs, p. 193-194, 211, 223; Paul Godaert, Les présidents des brasseries Artois: Léon Verhelst, Henry van den Schrieck, Werner de Spoelbergh, Raymond Boon, Virton 1993, p. 30-31.

[14] Chris Vandewalle, De bierslag van Zannekin. De mouterij-brouwerij St.-Louis in Lo (19de – 20ste eeuw), Alveringem 2004, p. 32. A copy was courteously provided to me by the author.

[15] City archives of Dendermonde, Archive brewery G. Blancquaert en G. Matthys, inv. no. 715.

Interesting read if famous beer style and I love it. Happens to be a fantastic cobbled classic tour of Flanders for cycling purists and the two go hand in hand!

In the UK, until the 1960s, it was usual to mix the draught ale with a bottle of hoppy pale ale/stout/barley wine. Is it possible that the brown beer that ‘sears the throat’ was mainly used as an optional mixer with the uitzet?