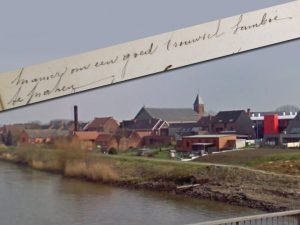

A lambic from Eastern Flanders from the early 1900s

If there is one Belgian beer of which its fans want to know all about its history, it has to be lambic. This extraordinary beer from the Brussels region is surrounded by an aura of age-old tradition: supposedly, it is a kind of ‘primordial beer’ from the Middle Ages. Even more so, the ‘High Council for Artisanal Lambic beers’ HORAL (which is an incredibly pompous name, what’s wrong with just calling yourselves ‘Association of Lambic Brewers’?) pretends that ‘the first lambic was already brewed before the year 1300’.[1]

If there is one Belgian beer of which its fans want to know all about its history, it has to be lambic. This extraordinary beer from the Brussels region is surrounded by an aura of age-old tradition: supposedly, it is a kind of ‘primordial beer’ from the Middle Ages. Even more so, the ‘High Council for Artisanal Lambic beers’ HORAL (which is an incredibly pompous name, what’s wrong with just calling yourselves ‘Association of Lambic Brewers’?) pretends that ‘the first lambic was already brewed before the year 1300’.[1]

Just to be clear: a lot of claims about the history of lambic are based on, to put it mildly, sloppy research and wishful thinking. The main error is in the basic assumption that lambic is an uncorrupted relic from the past, and that it has never changed throughout the centuries. The traditional perception by both lambic brewers and drinkers, a perception that has been around for the past fifty years or so, is that in the Middle Ages all beers were a kind of lambic: no yeast added and deliberately soured in barrels.

Nothing is less true: all data we have show that during the Middle Ages people simply did add yeast to beer. They also did in Belgium, for instance in the city of Tienen, were in 1533-1534 the city council had beer brewed from wheat, barley, spelt, hop and ‘gheste’ (yeast).[2] Also, beer was drunk relatively fresh. In those days, beer didn’t even get the chance to sour for years in barrels: people simply didn’t keep it that long.

Book of brewer’s notes, from the Blancqaert-Matthys brewery in Schoonaarde. City archives, Dendermonde.

In reality, the practice of deliberately keeping beer for a long time to obtain a pleasant tart flavour, is typically something of the 18th century. English porter beer, first mentioned in 1721, was a good example: for months it would be kept in large vats at the brewery, to obtain the right mild sourness (it only became sweeter at the end of the 19th century).[3] Holland knew ‘old beer’, ‘kept beer’ and ‘old brown’, and in Belgium faro interestingly is first mentioned in 1721 as well. Lambic, initially just a stronger sibling of faro, only surfaced in 1794.[4]

I hope I have made clear that there’s still a lot of research to be done about the truth on lambic. And on faro, today a sweetened, brown-coloured variant, but originally just the weaker original version of lambic. So when did people start to sweeten faro? Another question is the use of hops: today, lambic brewers use only old hops, that have already lost their aroma and are only used for their bitterness and preservative qualities. But in the mean time I have found quite a lot of 19th-century documents which indicate that in those days lambic brewers preferred fresh hops.

Also, there is the question: where can you brew lambic? In other words, where does the air contain the right yeasts and other small creatures to make a spontaneous fermentation possible, without actively adding any yeast? Not just in the Zenne valley in and around Brussels, as many people believe. In the 19th century lambic was even made across the border in the Netherlands, as far as Haarlem, where I found a 1820 lambic in the brewing logs.[5]

All in all it’s very useful to find more historical data on lambic. That’s why I was happy to do a lucky find in the records of village brewery Blancquaert-Matthys in Schoonaarde, in the Belgian province of East Flanders. This well-thumbed booklet contains a ‘Method for making a good brew of lambic’, from somewhere between the years 1903-1907.[6]

Brewer Guillaume Matthys, posing with what appears to be a large fish. From: Stroobants, Tussen pot en pint.

At that moment, Guillaume Matthys had just taken over his father-in-law’s brewery and was modernising it.[7] The brewery produced mainly all sorts of brown old beer, which for every customer was mixed differently, from various starting beers (to be exact, from ‘dobbel bier’, ‘versnijbier’, ‘ongedreven bier’ and ‘vers bier’. I’ll get back to these soon).

Did Guillaume Matthys actually brew lambic in Schoonaarde, at just 35 km from Brussels but well outside the Zenne valley? Or did he simply copy a recipe from somewhere, and nothing more? The recipe contains some dialect words (‘zooien’ for ‘to boil’ and ‘meyst’ for ‘March beer’), which seems to indicate that he really did write it down in his own words. All in all it is a fun recipe, though not always very clear. And of course, lambic is the sort of beer that is hard to pin down in a recipe, because the real magic happens only after brewing: during maturation (in this recipe, it takes four years) and blending. Interestingly, in this recipe faro is already sweetened. It was made from 50% lambic and 50% ‘meyst’ (weaker March beer), with one kilogram of candy sugar per 40 litres of beer added.

The Blancquaert-Matthys brewery, which existed from about 1880 until 1918, is worth investigating more closely. Not in the least because a small part of the buildings still exists, along the river Scheldt. That’s why I certainly will get back to it. But first let’s have a look at their lambic recipe. I’ll quote the full thing in Dutch, then I’ll draw some conclusions:

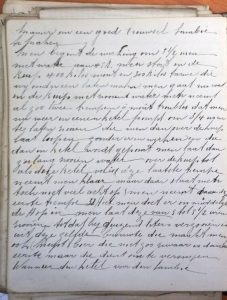

Manier om een goed brouwsel lambic te maken

Men begint de werking om 5½ uren met water aan 45 R [56,3º C]. Men stort in de kuip 400 kilos mout en 300 kilos tarwe, die wij onder een laten maken. Men gaat nu voort in de kuip met zooiend [kokend] water. Men neemt alzoo twee trempen à moût trouble [treksels troebel wort] dat men nu weer in eenen ketel pompt om ¾ uren te laten zooien [koken], die men dan over de kuip laat loopen zonder erin werken en die dan in [de] ketel wordt gepompt. Men laat dan zoo lang zooien[d] water over de kuip tot als deze ketel vol is (deze laatste trempe neemt men klaar maar daar slaat men toch niet veel acht op).

Men neemt daar de eerste trempe 32 hect. Men doet er onmiddellijk de Hop in, men laat deze van 5 tot 5½ uren zooien totdat hij duizend liters verzooien is.

Uit deze zelfde brouwte die maakt men ook (meyst) bier die niet zoo zwaar is dan het eerste maar die dient om te versnijen.

Wanneer den ketel voor den lambic vol is die roert men weder in de kuip met bijvoeg van zooient water, men laat een weinig rusten en men zendt dan den slijm ook naar den ketel om te zooien (niet in den zelfden ketel van den lambic). Men maakt daarvan 28 Hectol. die men ook langen tijd laat zooien 10H men doet in de twee ketels 5 pond Hop per 100 kilos mout, voor het klein bier roert men noch eens. Deze laat men zooien in den ketel van den lambic die nu al reeds op den koelbak staat.

Het bijzonderste punt is goed zooien hoe meer hoe beter, want anders wordt dat bitter en zuur, deze blijft gewoonlijk 4 jaar in den kelder liggen omdat hij hem niet zouden keeren wanneer hij uitgevoert wordt.

Faro: den helft lambic en meyst en een kilo kandeelsuiker vloeibaar gemaakt met warm water per 40 liters.

Men klaart met peau de … en accide tartrique.

Altogether, the recipe does not excel in clarity. In any case there are multiple mashes (‘trempes’) from the grain, and there are two brewing kettles. There is the ‘regular’ boiling kettle, and a separate kettle for the ‘slime’, a first turbid mash that is boiled for a short while and then poured over the grain again, causing the temperature in the mash tun to rise, starting a new phase in the mashing process.

Breaking the recipe apart, I get:

- The brewery consists of a mash tun, two kettles (the ‘lambic kettle’ and the ‘slime kettle’) and a coolship.

- 400 kg of barley malt and 300 kg of unmalted wheat are put into the mash tun, which already contains water at 56,3ºC.

- Two mashes of turbid wort are subtracted and boiled separately in the slime kettle, for 45 minutes.

- This boiling ‘slime’ is poured back into the tun. The temperature in the tun rises, enabling sugar formation.

- 32 hectolitres of wort are subtracted from the tun, into the lambic kettle, where it is boiled with hops (17.5 kg) for 5 to 5½ hours.

- The tun, still containing the grain, it filled to the brim with boiling water (boiling water would be too hot for saccharification, so probably the recipe means hot, but not boiling water).

- One mash from the tun is pumped into the slime kettle, where it is boiled and then poured back into the tun. The temperature inside the tun rises, enabling saccharification.

- In the mean time, the first mash is poured from the lambic kettle onto the coolship, where it can cool down and then start fermenting.

- The second mash is subtracted from the mash tun and pumped into the lambic kettle, 28 hectolitres. It is boiled for 10 hours with 17.5 kg of hops. This will become the ‘meyst’ or March beer that serves for blending.

- The lambic is kept in the cellar for four years.

- Faro is made out of a blend of 50% lambic and 50% March beer, adding one kg of candy sugar (made liquid with hot water) per 40 litres of beer.

Now I would very much like to ask for your expert opinion: is this a workable interpretation? Or does the original text imply something else? Is the result a workable lambic? I’m looking forward to reading your comments.

[1] http://horal.be/lambiek-geuze-kriek/lambiek

[2] J.P. Peeters, ‘Bieraccijnzen en bierproduktie te Tienen op het einde van de Middeleeuwen en in de 16de eeuw’, in: Eigen schoon en de Brabander, volume LXX nr. 1-3 (Januari-March 1987) p. 1-26 and volume LXX nr. 4-6 (April-June 1987) p. 155-180.

[3] Martyn Cornell, Amber gold and black, Stroud 2010, p. 53-78.

[4] Jacob Campo Weyerman, De Rotterdamsche Hermes, Amsterdam 1980, p. 391; Thierry Delplancq, ‘Les brasseurs de lambic. Données historiques et géographiques (XVIIIe S. – XXe S.) (1)’, in: Archives et bibliothèques de Belgique, deel 67 (1996), nr. 1-4, p. 257-320, here p. 260. Cf. http://lostbeers.com/lambic-the-real-story/

[5] http://verlorenbieren.nl/verloren-bieren-33-de-bieren-van-t-scheepje/; http://lostbeers.com/dutch-faro-and-lambic-revisited/

[6] Stadsarchief Dendermonde, Archief brouwerij G. Blancquaert en G. Matthys, inv. no. 715.

[7] Aimé Stroobants, Tussen pot en pint. Herinneringen aan de Dendermondse brouwers, Dendermonde 1990, p. 80-81.

Fascinating!

This is the classic “turbid mash” method, is it not? Developed to utilise the smallest possible tin and minimise tax exposure?

You translate that two turbid mashes are drawn from the tun and boiled separately. Why are they boiled separately, and where does the first one sit while the second one is boiling? Or does this simply mean that drawing off the slime, boiling it and adding it back to the tun was done twice (which would fit with turbid mashing)?

One can see how this would leave a wort packed with complex carbohydrates, which would feed the wild yeasts and bacteria for months and tears.

Reads like a lot of English mash procedures around the same time in which part of the runnings are boiled with hops while the mash continues and everything is boiled together. Not sure I’ve seen a turbid mash call for hops midway through but I wouldn’t be surprised if it happened more frequently.