Dutch Faro and Lambic

Belgium has its lambic, faro and geuze, spontaneously fermented beers that can only be produced in the Zenne valley and the Pajottenland near Brussels. Or can they? Learn about the historical Lambic beers of Holland. With a recipe.

Belgium has its lambic, faro and geuze, spontaneously fermented beers that can only be produced in the Zenne valley and the Pajottenland near Brussels. Or can they? Learn about the historical Lambic beers of Holland. With a recipe.

For those who need to refresh their memories: lambic is a traditional Belgian beer made of barley and wheat. No yeast is added, the wort (the beer-to-be) is just exposed to the air. Small yeast particles that are present in the environment then end up in the wort and take care of the rest. The beer is then left to age in oak barrels for two years. Pure lambic is hard to come by: old lambic is usually blended with young beer to become geuze. If sugar is added, it becomes faro, and with sour cherries it becomes kriek.

‘Kriek’ means ‘cherry’, but oddly the other names have an obscure origin. The earliest mention of faro in a Brussels context dates back from 1721.[1] An official document from 1794 gives an early mention of four barrels of ‘allambique’ at a Brussels brewery. [2] Judging by the name ‘allambique’, it was probably derived from the alembic, an apparatus used in distilling alcohol, though why it is hard to say. Geuze is first mentioned in a survey of Belgian brewing methods in 1829.[3] It is interesting to note that HORAL, the ‘High Council for Artisanal Lambic beers’ seems to have missed most of this information, the dates they provide are much younger.[4] At the same time, the 1559 ‘lambic recipe’ often mentioned in their documentation is complete bollocks, as Belgian historian Raf Meert has convincingly shown. The 1559 Halle brewer’s law doesn’t mention lambic but does mention a third of oats, a fact conveniently concealed by the lambic propaganda.[5]

Forget about HORAL’s claims, just remember that it is a great beer. As a beer type, it just isn’t particularly old, and was actually preceded by eighteenth-century English porter, which originally, after all, was also a beer matured in barrels. Anyway, if we look at brewing literature from the era, the production methods of these early lambics must have been similar to today’s. In 1834, David Booth in his book ‘The art of brewing’ already describes the ‘spontaneous fermentation’ that the brewers of Brussels used. There were also some differences: the amount of wheat used was higher, at least 50%.[6]

The first mention of these great beers in the Netherlands (or Holland) dates from 1811. In Amsterdam, 200 km to the North of Brussels, A. Oortmans and Co. announced they would sell ‘first class Brussels Faro and Lambicq’ that year. At the time, Holland was not really a beer drinking nation anymore. The Dutch preferred coffee, cocoa, tea and gin. The sudden interest in faro therefore had a reason: Holland was at that time part of France. Napoleon had decreed a boycott of trade with England and overseas. Prices of coffee and tea soared. What to do? Drink beer, of course. In 1812 an inn keeper in Groningen, even more to the North, announced that ‘because of higher prices of Coffee and Tea, and the greater consumption of Beer’ he supplied ‘Brussels Pharo’ among other things. In the decades that followed, more faro and lambic were sold in Holland, usually described as ‘from Brussels’ of ‘from Brabant’ (the region in which Brussels was situated).

And then… Belgium declared its independence. Since 1815 it had been one country together with Holland, but the Belgians were fed up with the Dutch regime and decided that it was time to go their own way. Immediately, the supply of faro to Holland stopped. There was however still demand for the spontaneously fermented Brussels beers. So the Dutch scratched behind their ears, and thought: can’t we make these beers ourselves?

And so, the Scheepje brewery in Haarlem, 20 km from Amsterdam, announced in 1833 that ‘because of the separation of Belgium, they have now applied themselves especially to the Brewing of Faro and Lambiek’. Even King William I’s court was one of their customers. Other Dutch brewers had already done likewise, like in Utrecht (1812), Zierikzee (1814), Schoonderloo near Rotterdam (1830) and Leeuwarden (1831).[7]

And so, the Scheepje brewery in Haarlem, 20 km from Amsterdam, announced in 1833 that ‘because of the separation of Belgium, they have now applied themselves especially to the Brewing of Faro and Lambiek’. Even King William I’s court was one of their customers. Other Dutch brewers had already done likewise, like in Utrecht (1812), Zierikzee (1814), Schoonderloo near Rotterdam (1830) and Leeuwarden (1831).[7]

And after that, it just spread like wildfire in Holland. All sorts of Dutch breweries started making their own version of faro and lambic. In towns like Leiden, Arnhem, Utrecht, Maastricht, Amsterdam… Though the lambics were only part of a larger range of Dutch beers, their heyday must have been around 1840-1880. However, by 1893 Van Renesse in Gorinchem was still making faro, and the last brewery known to so was De Sleutel in Dordrecht, until at least 1933. Which is over a century of Dutch faro and lambic production![8]

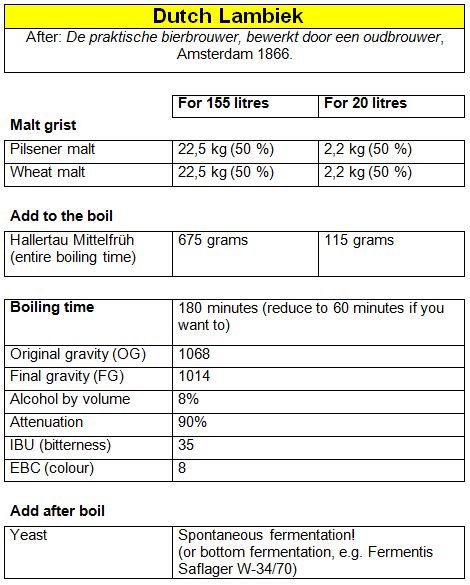

So what about spontaneous fermentation, the heart and soul of the lambic? Which according to today’s Brussels brewers’ claims, can only happen in their region? Did the Dutch succeed in that too? Well, yes they did. Or at least if we can believe De praktische bierbrouwer (‘The practical beer brewer’), a brewer’s manual published in Amsterdam in 1866. Indeed the brewer had to ensure ‘a kind of self-fermentation’ without the adding of yeast, by putting it in a ‘very cool cellar’. Though it was possible to cheat: ‘some brewers add 200 grams of yeast to the barrel, and have the beer undergo a bottom-fermentation’.[9] Oh well…

Of course, in Belgium the production of lambic has always continued. The great beers of the brewers of Brussels gained a deserved fame among beer lovers. In 1997 the names lambic, geuze, faro and kriek were protected by the European Union. However… look at the small print: they are all ‘Traditional specialities guaranteed’. In other words: the production methods are protected, but it is no protected designation of origin. Anyone who wants to make faro or geuze, wherever in the world, can do so as long as it is done in the right way. Already, a few small Dutch breweries are doing so, like Eanske and Toon van den Broek. De Molen has made a ‘Morellenlambiek‘ (cherry lambic). And why not? The Dutch do have some historical rights here…[10]

Of course, in Belgium the production of lambic has always continued. The great beers of the brewers of Brussels gained a deserved fame among beer lovers. In 1997 the names lambic, geuze, faro and kriek were protected by the European Union. However… look at the small print: they are all ‘Traditional specialities guaranteed’. In other words: the production methods are protected, but it is no protected designation of origin. Anyone who wants to make faro or geuze, wherever in the world, can do so as long as it is done in the right way. Already, a few small Dutch breweries are doing so, like Eanske and Toon van den Broek. De Molen has made a ‘Morellenlambiek‘ (cherry lambic). And why not? The Dutch do have some historical rights here…[10]

Mash at 50ºC. Leave the first running for half an hour, then boil one third for half an hour, and then put back into the running. The first running is now 75ºC. Keep second running in rest for an hour at 85ºC. Add third running to the whole, then boil. After boiling, keep standing for an hour so that the proteins can sink to the bottom. Close barrels only loosely, close well after three days.

Faro grist (in this book a separate beer) is similar, but now 26,5 kg of barley and 13,25 kg of wheat (2 to 1), and use 200 grams of hops.[11]

[1] Jacob Campo Weyerman, De Rotterdamsche Hermes, Amsterdam 1980, p. 391. In the 16th century there existed a ‘pharao’ beer in Holland and Zeeland, also written as ‘pharo’ or ‘faro’. In those regions, it was the strongest beer around at that time, and its slightly weaker sibling was called israel. Both names clearly refer to the Bible. According to German cleric Heinrich Knaust, writing in 1575, israel was originally from the German town of Lübeck, where it was a white beer. However, by the end of the 17th century pharao and israel had all but disappeared, and it is hard to see how Brussels faro is connected to the earlier pharao, especially as no information has yet been found about the latter’s characteristics or brewing process.

[2] Thierry Delplancq, ‘Les brasseurs de lambic. Données historiques et géographiques (XVIIIe S. – XXe S.) (1)’, in: Archives et bibliothèques de Belgique, part 67 (1996), nr. 1-4, p. 257-320. 260. Raf Meert (lambik1801.be) gives a slightly earlier mention of lambiek in his article ‘Eerste lambik komt niet uit Lembeek’ but provides no source.

[3] Jean Baptiste Vrancken, ‘Antwoord op vraag 81’, in: Nieuwe verhandelingen van het Bataafsch Genootschap der Proefondervindelijke Wijsbegeerte te Rotterdam, Rotterdam 1829, p. 77.

[4] http://www.horal.be/lambiek-geuze-kriek/oorsprong. An English-language version of this page is not yet provided.

[5] Raf Meerts, ‘Hals bier uit 1559 is geen lambik’ (deel 1 en 2); ‘Lambiek is niet oudste bier van België’, on lambik1801.be. De Standaard 27-2-2014. http://www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20140227_01001636.

[6] David Booth, The art of brewing, Londen 1834, deel III p. 44-45. Compare Vrancken, ‘Antwoord’, p. 6, 207; Georges Lacambre, Traite complet, p. 339. According to Raf Meerts (lambik1801.be) it could also be 2/3 of wheat, but he provides no sources for this claim.

[7] Opregte Haarlemsche Courant 19-3-1833. The brewing records actually show the Scheepje brewery had been making Lambics since 1823.

[8] Nieuwe Gorinchemsche Courant, 9-3-1893, De Telegraaf 28-07-1933.

[9] De praktische bierbrouwer, bewerkt door een oudbrouwer, Amsterdam 1866, p. 96-97.

[10] This article was based on an earlier version in Dutch, http://verlorenbieren.nl/verloren-bieren-22-nederlandse-faro-en-lambiek/.

[11] De praktische bierbrouwer, bewerkt door een oudbrouwer, Amsterdam 1866, p. 96-97. Calculation made with Brewer’s Friend recipe builder, with 75% efficiency. The original recipe speaks of ‘white malt’ instead of Pilsener, and of Flemish hop instead of Hallertau.

Leave a Reply