Dutch faro and lambic revisited

In the previous article I summarised what lambic mythbuster Raf Meert had found out about the history of this wonderful beer type from Brussels and surroundings. To put it briefly: everything lambic brewers’ association HORAL and self-proclaimed authorities like beer writer Jef van den Steen had claimed so far on this subject is embarrassing hokum, unfortunately. In reality, this remarkable tart beer doesn’t go back further than the eighteenth century, and it contained a lot more wheat than today. Initially faro was the strongest kind of yellow beer, until the even stronger lambic appeared. So here’s my contribution: how do the faros and lambics of the Netherlands fit into this story?

In the previous article I summarised what lambic mythbuster Raf Meert had found out about the history of this wonderful beer type from Brussels and surroundings. To put it briefly: everything lambic brewers’ association HORAL and self-proclaimed authorities like beer writer Jef van den Steen had claimed so far on this subject is embarrassing hokum, unfortunately. In reality, this remarkable tart beer doesn’t go back further than the eighteenth century, and it contained a lot more wheat than today. Initially faro was the strongest kind of yellow beer, until the even stronger lambic appeared. So here’s my contribution: how do the faros and lambics of the Netherlands fit into this story?

To Belgians this may be blasphemy, but once there existed an ‘Amsterdams lambiek’ and lambic from many other Dutch cities too.[1] I had already described how from 1812 onwards Dutch brewers imitated the faro and lambic from ‘Brabant’, and how popular these beers were in Holland in the middle of the nineteenth century. Unfortunately, back then I still wrote with the current definition of these beers in mind: lambic the sour ‘starting beer’ which is only sparsely commercialised nowadays, faro one of the blended beers made from it, namely a sweetened, less strong variant. That’s why I was already surprised to find separate brews and recipes of faro by itself: I thought it was a blend? And why didn’t the Dutch brewers make gueuze, that other lambic blend known for its foaming champagne-like properties?

Well, the problem was that I projected today’s lambic, faro and gueuze onto the beers of the past. A mistake also made by the Belgians until now, or for instance by the writers of a book about the beers of Dordrecht, where a 1577 ‘Pharao’ beer is claimed to have had the same properties as today’s Brussels faro.[2] In reality, there is no reason to assume this, especially seen in the light of what we know now. If a sixteenth century text mentions a ‘car’ it doesn’t mean an automobile, a ‘lamp’ was no LED spotlight, and a ‘mouse’ wasn’t a device to control your computer.

Well, the problem was that I projected today’s lambic, faro and gueuze onto the beers of the past. A mistake also made by the Belgians until now, or for instance by the writers of a book about the beers of Dordrecht, where a 1577 ‘Pharao’ beer is claimed to have had the same properties as today’s Brussels faro.[2] In reality, there is no reason to assume this, especially seen in the light of what we know now. If a sixteenth century text mentions a ‘car’ it doesn’t mean an automobile, a ‘lamp’ was no LED spotlight, and a ‘mouse’ wasn’t a device to control your computer.

So, I had to go back to the data I had collected and look at them again with new eyes. Firstly, the price difference. According to Raf Brussels faro had emerged in the eighteenth century as the most expensive beer of that city. Then in 1794 lambic surfaced as its even more expensive brother. If you stop and think about it, you understand why faro became a blended beer in the end: why brew it separately, if you can just make stronger lambic and then dilute it? This I how faro as a blend must have emerged, which then developed into a sweetened version, while the gueuze, in circulation from at least 1829, remained sour.

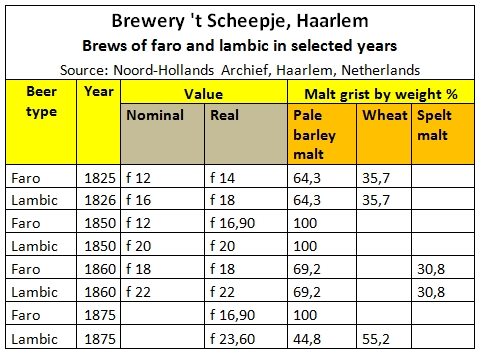

It’s time to look at some Dutch data. A nice series of faros and lambics can be found at the Scheepje in Haarlem, a brewery that I looked at before in several articles in Dutch. If I take a few sample years, this is what you get:[3]

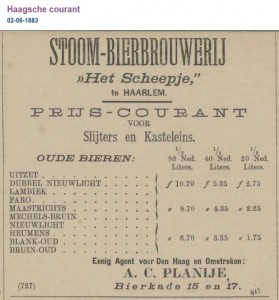

Here, every time lambic was the more expensive and therefore heavier beer, while the percentage of wheat was often similar for both faro and lambic, even though no wheat at all was used in 1850, and in 1860 they used spelt! Still, until the very end (the series of data ends in 1876) faro was brewed separately, and both beers were in the highest price category. In 1883 their lambic was (in a The Hague newspaper advert) still one of their most expensive beers at f 10,70 per 80 litres, and their faro only slightly cheaper at f 8,70.[4]

Here, every time lambic was the more expensive and therefore heavier beer, while the percentage of wheat was often similar for both faro and lambic, even though no wheat at all was used in 1850, and in 1860 they used spelt! Still, until the very end (the series of data ends in 1876) faro was brewed separately, and both beers were in the highest price category. In 1883 their lambic was (in a The Hague newspaper advert) still one of their most expensive beers at f 10,70 per 80 litres, and their faro only slightly cheaper at f 8,70.[4]

Another nice source that I have often quoted from, is the Dutch book De praktische bierbrouwer (The practical beer brewer) from 1866, which contains a recipe for both faro and lambic in the ‘Belgian beer’ chapter. Interestingly, the book says it is indeed necessary to ‘accomplish a sort of self-fermentation, by putting the brew in small barrels and putting them in a cool cellar’. Spontaneous fermentation then, just like they still do in Brussels and surroundings, and what was apparently also possible in the Netherlands. However, even though ‘usually no yeast is added to this beer’, some brewers would ‘add 200 grams of yeast to the tun and have the beer undergo a bottom fermentation.’[5]

The descriptions of recipes in this book are somewhat messy, but for lambic a malt grist of 90 pounds was needed, and for faro 80 pounds. With an attenuation of 80% that would mean beers of 7,2% and 6,4% alcohol by volume respectively. The amount of malted wheat in lambic was no less than 62,5% and for faro 45,5%, however in a table further on it is only 33% and 25%. There is no information given about the ageing process, for instance how long it should take or what should be done with the beer afterwards. Therefore there seems to be no difference between the two beers except for the malt grist, to faro no sugar or anything similar is added and in every respect ‘Faro is treated like Lambic’.[6]

The price difference between lambic and faro seems to have been an enduring feature in Holland. A collection of beer prices from various breweries in 1873 shows that lambic cost an average f 10,30 per 80 litre barrel, and faro f 8,85. Only in Utrecht, at both the Boog and Krans breweries, lambic and faro were, strangely enough, of the same price. So there the difference was not the price but something else? Unfortunately, there are no brewing records available for these.

The price difference between lambic and faro seems to have been an enduring feature in Holland. A collection of beer prices from various breweries in 1873 shows that lambic cost an average f 10,30 per 80 litre barrel, and faro f 8,85. Only in Utrecht, at both the Boog and Krans breweries, lambic and faro were, strangely enough, of the same price. So there the difference was not the price but something else? Unfortunately, there are no brewing records available for these.

After 1890 the heyday of Dutch lambic was over. The last old-fashioned breweries to produce it, like the aforementioned Scheepje in Haarlem, Corman in Vlijmen and De Kraan en de Drie Snoeken in Gorinchem gave up around this time, according to newspaper adverts. Also, it was only sparsely imported: only the Café Belge in The Hague would still advertise its ‘Real Brussels Faro’ and something called ‘Kalos (half Faro half Lambiek)’.[7] Yet, this was not entirely the end. In the years 1901-1903 the Royal Halsche Steam brewery, in a hamlet near Boxtel, would still advertise its lambic and faro. [8] In 1922 and 1924 we see ‘Speciality Faro, Lambique’ at the Gekroonde Bel in Oosterhout, which, oddly, was a modern Bavarian-style brewery.[9]

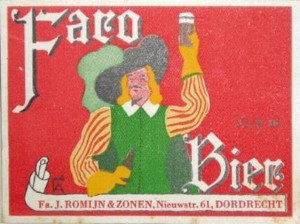

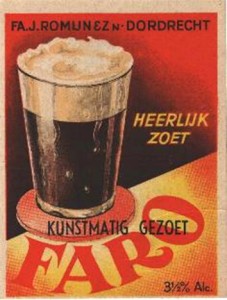

Still, even they weren’t the last one. That was De Sleutel (‘The Key’) in Dordrecht, that did not advertise a lot in newspapers, but of which there is a known faro label from around 1910, and a few labels that date from the 1930s, judging by the fact that they state the alcohol content (3,5 % ABV).[10] This is confirmed by the fact that when the brewery celebrated its presumed 500th birthday in 1933, the newspaper wrote that the sixteenth-century ‘pharao’ beer was still commercialised under the name ‘Faro’.[11] The link with ‘pharao’ is stretching it a bit too far, because in the Netherlands this ‘pharao’ beer went extinct in the 17th century, as far as I can tell.[12] Anyway, this 1933 faro must have been the last one made in Holland, made for the Dordrecht lemonade factory and wine trader J. Romijn. Some labels say it was ‘deliciously sweet’ and even ‘artificially sweetened’, so it must have been similar to the sweetened faro made in Belgium nowadays. Moreover, the glass shown on the label suggests it was a brown beer at this point.

Still, even they weren’t the last one. That was De Sleutel (‘The Key’) in Dordrecht, that did not advertise a lot in newspapers, but of which there is a known faro label from around 1910, and a few labels that date from the 1930s, judging by the fact that they state the alcohol content (3,5 % ABV).[10] This is confirmed by the fact that when the brewery celebrated its presumed 500th birthday in 1933, the newspaper wrote that the sixteenth-century ‘pharao’ beer was still commercialised under the name ‘Faro’.[11] The link with ‘pharao’ is stretching it a bit too far, because in the Netherlands this ‘pharao’ beer went extinct in the 17th century, as far as I can tell.[12] Anyway, this 1933 faro must have been the last one made in Holland, made for the Dordrecht lemonade factory and wine trader J. Romijn. Some labels say it was ‘deliciously sweet’ and even ‘artificially sweetened’, so it must have been similar to the sweetened faro made in Belgium nowadays. Moreover, the glass shown on the label suggests it was a brown beer at this point.

Oddly, the Sleutel brewing records show they had only made bottom-fermented beers like lager, pilsener, Munich and bock from 1918 onwards. However, we shouldn’t forget that De Sleutel was also still making its aged Christmas beer Paulus Jonas, even until 1945. It seems they still had the know-how to make (bottom-fermented) aged beers.

Now for a conclusion: it seems that Raf Meert’s vision on historical lambic is also valid for the Netherlands, to a certain degree. Just like initially in Brussels, Dutch lambic and faro were similar beers, the one was just heavier than the other, and both beers were in the highest price category. Moreover, in Holland faro was generally not a blend of lambic, both beers were brewed separately, as far as I know. Though usually wheat beers, they were also made of only barley malt or sometimes even with spelt malt instead of wheat. And initially there is no indication that faro was sweetened, but interestingly it surely was in the 1930s in Dordrecht, just like they would do with Brussels faro at that point. In a way that last Dutch faro had evolved in the same direction as its bigger Brussels counterpart.

[1] Provinciale Overijsselsche en Zwolsche courant 2-11-1885.

[2] Herman A. van Duinen et al. (red.), Water wordt een feest als het bij de brouwer is geweest. Dordtse brouwerijen door de eeuwen heen (Jaarboek Historische Vereniging Oud-Dordrecht 2007), Dordrecht 2007, p. 165.

[3] Noord-Hollands archief, Archief bierbrouwerij ’t Scheepje te Haarlem , inv. no. 198, 200, 201 Stort- en peilboeken.

[4] Haagsche courant 2-6-1883.

[5] De praktische bierbrouwer, bewerkt door een oudbrouwer, Amsterdam 1866, p. 96-97.

[6] Praktische bierbrouwer, p. 96-97, 116.

[7] Haagsche courant 12-5-1890.

[8] Provinciale Noordbrabantsche en ‘s Hertogenbossche courant 6-9-1901.

[9] Bredasche courant 29-7-1922, 4-10-1922, 26-7-1924.

[10] Regionaal archief Dordrecht, Archief brouwerij De Sleutel, inv no. 61; http://www.bieretiketten.nl/cms/index.php?page=Etikettenoverzicht&paginanr=sleutel——–001-50.

[11] Telegraaf 28-7-1933.

[12] In the 17th century in the Netherlands, pharao beer was also called ‘faro’. The last known mention of a beer brewed within the Republic (in the province of Zeeland) dates however from 1685 (G.A. Fokker, ‘Taalkunde’, in: De Navorscher, volume 25 (1875), p. 61-64.). It is possible that this 16th and 17th century pharao/faro gave its name to the Brussels beer of the same name (the first mention of faro in a Brussels context dates from 1721), but there is at his moment not enough data to say anything conclusive on this matter. At least, the fact that pharao in the Netherlands was the strongest beer of its day, and that Brussels faro initially held a similar position, is a similarity between the two.

Leave a Reply